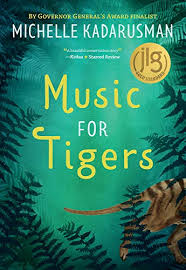

Music for Tigers by Michelle Kadarusman

Michelle Kadarusman writes about her new novel Music for Tigers at PaperbarkWords:

As an Australian living abroad, you are heightened to any mention of home in North American media. It doesn’t happen that much and when it does it’s somehow personally reaffirming. It’s one of the quirks of living far from your birth place and even after decades away the homesickness never leaves you. So, when The New Yorker ran a feature about a group’s obsessive search for the Tasmanian tiger, I was giddy. Not only because of the automatic reaction of Look! Look! There’s something about Australia in The New Yorker! but also because of my long-held fascination with the haunting and tragic history of the thylacine and the continuing mystery of whether it still exists. I must have talked to many people over the years about this particular interest because The New Yorker article landed in my INBOX multiple times forwarded by friends including my editor at Pajama Press, Ann Featherstone. Ann included a short note saying something along the lines of… time to get going on that story you told us about. It’s not that my editor and publisher were totally off the middle grade thylacine story I had pitched to them a few months earlier (hmm, ok, so where is it set? Tanzania?) – but now my mysterious animal and obscure location had been legitimized to their North American ear.

Within weeks I had packed a bag and set off to the Tarkine region of Tasmania to research the book. Ethereal is perhaps too flowery a word for this experience, but I can’t think of another to describe delving into the history of the thylacine while soothing my eternal homesickness. The Tarkine is a breathtaking place and walking through the ferns and blue gums of my childhood, listening to currawong birdcalls while breathing in the scent of lemon myrtle and eucalyptus was intoxicating. And peeking down the shadowy trails of the temperate rainforest it was easy to imagine a thylacine crouching there, ready to come out for a brief but starring role in my story.

Music for Tigers is about a young Canadian girl who is sent to her Australian family’s bush camp in the Tarkine, where she discovers her great-grandmother harboured a secret sanctuary for the thylacine and her family have been trying to protect endangered species ever since.

Writing from the perspective of a Canadian protagonist, I was able to introduce the magic and beauty of the Australian landscape to young North American readers in a way that may not have been as impactful if the character was local. And although I didn’t do it consciously, writing a reverse outsider scenario to my own was wonderfully satisfying.

Happily, since writing the story I now live a good portion of the year in Australia, so while my yearning for Oz has eased Music for Tigers remains to be my love letter to the Australian bush and to the unique animals that once and still thrive within it.

And a place that will forever and always be home.

International honours for Music for Tigers:

USBBY Outstanding International Book, Washington Post KidsPost selection, 2020 Kirkus Best Book, 2021 Green Earth Book Awards Honor title and a 2021 White Raven Selection

My interview with Michelle about Girl of the Southern Seas

My interview with Michelle about The Theory of Hummingbirds

I reviewed Music for Tigers for the Weekend Australian (read below in bold)

Paws for Thought

MUSIC FOR TIGERS

By Michelle Kadarusman

Pajama Press, 192pp, $19.99

THE BOY, THE WOLF, AND THE STARS

By Shivaun Plozza

Puffin, 384pp, $16.99

WE WERE WOLVES

By Jason Cockcroft

Andersen Press/Walker Books, 216pp, $26.99

THE LAST BEAR

By Hannah Gold, illustrated Levi Pinfold

HarperCollins, 304pp, $19.99

Joy Lawn

Bears, wolves and big cats abound in literature for young people and, in the best of these works, are a metaphor for wildness, power and unpredictability or are a conduit to explore fear or grief. Their endangerment and loss also embody the threat to our natural world.

Middle-fiction, also known as middle-grade books for readers aged about 10-14 years, is a flourishing sector of the publishing industry. It intersects with the younger end of the young adult market.

Four novels recently published for this age-group are notable. One explores the fate of the elusive Tasmanian Tiger, two feature wolves and the fourth highlights a bear.

In Music for Tigers, Australian-Indonesian author Michelle Kadarusman transplants violinist Louisa from Toronto to the Tarkine in the northwest Tasmanian wilderness. As soon as she arrives her musician’s senses are attuned to the currawongs who seem to be singing Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

Her Uncle Ruff runs a camp that is a haven for the endangered species that have lost habitats to land clearing and are threatened by invasive predators. It is to be bulldozed to make an access road to the tin and iron ore mines. Legendary Convict Rock, a landmass in the river, will be dynamited to become a bridge.

Louisa reads her great-grandmother Eleanor’s journal about her life in the bush in the 1930s and 40s. Eleanor established the camp for wildlife at risk and found a secret sanctuary on Convict Rock for the Tasmanian Tigers that were thought to be extinct.

Great-grandmother and granddaughter share a talent for music and it is Lou’s violin playing that lures the last thylacine in the area to her.

Music for Tigers explores Lou’s new friendship with neurodivergent Colin as well as Lou’s own performance anxiety. It has important conservation themes set in a real landscape that is almost magical in its dense lushness and beauty. It is told as a contemporary mystery using sensory, artistic images inspired by nature. The thylacine becomes a symbol of saving the lost in this moving, uplifting tale.

The Boy, the Wolf, and the Stars by Geelong-based author Shivaun Plozza is also intriguing and well composed and paced. Its style and mysterious elements derive from the quest fantasy and folklore genres. Wolves play multifaceted, sometimes subverted, roles and one is a major antagonist.

When 12-year-old orphan Bo fails his weekly task of sprinkling gold-red dust around the hunchbacked oldest tree in the forest, the force that constrains the Shadow Creatures is loosened. The island of Ulv has been overshadowed by the Dark since a bewitched wolf swallowed the stars to gain power to rule the land. The moon and constellations have been missing for so long that the people think they are a myth. Without their light, evil manifests in people and other creatures. The forest is dying and the Shadow Witch is allowing malevolent magic to seep back into the world.

Pursued and threatened by Ranik, his wolf nemesis, Bo and his cheeky fox friend Nix, apprentice healer Selene and the feathered Korahku who has the head of a human and body of a bird, must solve the riddles and face tests and trials to find the three keys to unlock the second wolf’s cage so that the stars can be released back into the sky and good magic can prevail.

Each major character undergoes a rite of passage in this original literary fantasy. Lies are revealed and they must all grapple with rejection, betrayal and anger before they can trust and forgive.

Metaphorical wolves and other wild creatures surface in We Were Wolves, written and atmospherically illustrated by Jason Cockcroft who created some of the iconic Harry Pottercovers. The unnamed boy protagonist lives in a caravan in the wood with his father John who has suffered from PTSD since his war service in Iraq and Afghanistan. John is about to return from prison.

The boy would prefer to live comfortably with his mother rather than endure the cold, lack of food and threat of eviction but his father’s head is “alive with beasts” and he needs help. He tells the boy about the ancient creatures that live under the ground: “beasts that had laid quiet under that wood for thousands of years finally climbed up out of the soil … like the bones of bears and wolves and wild bulls that are there if you dig deep enough.” Prehistoric creatures are stirring underground. The boy dreams of the yellow-eyed wolves awakening and clawing their way into the sunlight because John is coming home.

John is a damaged man. He is battered by his time as a soldier and ensnared in his criminal activities but loves his son in his own way and shares nature, and the art and poems of William Blake (“Tyger Tyger …”) with him.

While full of foreboding and foreshadowing, Cockcroft’s writing is lyrical with nuanced allusions to stars, butterflies and friendship to temper the darkness. This classic-in-the-making leaves us contemplating, who are the wolves?

The children’s novel The Last Bear by debut author Hannah Gold is enhanced by the art of Australian illustrator Levi Pinfold.

When a widowed meteorologist takes his 11-year-old daughter April to the Arctic Circle and neglects her she becomes friends with a polar bear, but is it real or imagined?

The inland lakes, beaches and trio of mountains on Bear Island are populated by rare birds and the Arctic fox but there are no bears. The melting ice caps have prevented them wintering there in recent years but, perceiving the place to have a “whisper of a magical fairy tale”, April thinks she sees a bear.

There is one starving young bear left on Bear Island and he is April’s secret. She has inherited her mother’s affinity with animals and slowly gains Bear’s trust through offering food and cutting the plastic twisted around his paw that stops him hunting. April knows that wild animals are dangerous and is cautious but the story she sees in his eyes shows that they share a bond of loneliness and grief.

Together they explore the coves and mountains. April learns to roar and “with each roar, she became a little bit more bear and a little less human. It didn’t matter how small she was. It only mattered how much she wanted to be heard”. However, her “iridescent shine of happiness” is threatened when her time on the island ends and she must reunite Bear with his mates.

The natural elements reflect and enrich the narrative. In an other-worldly scene April sights Bear in a mantle of fog, and the “hard, wrathful” waves emulate the pounding of grief and rage.

Plastic and litter; climate change and rising sea levels all mirror the wider world as April exemplifies how the young lead the way in saving the natural world.

Joy Lawn is a regular reviewer of literature for young people

One thought on “Music for Tigers by Michelle Kadarusman”