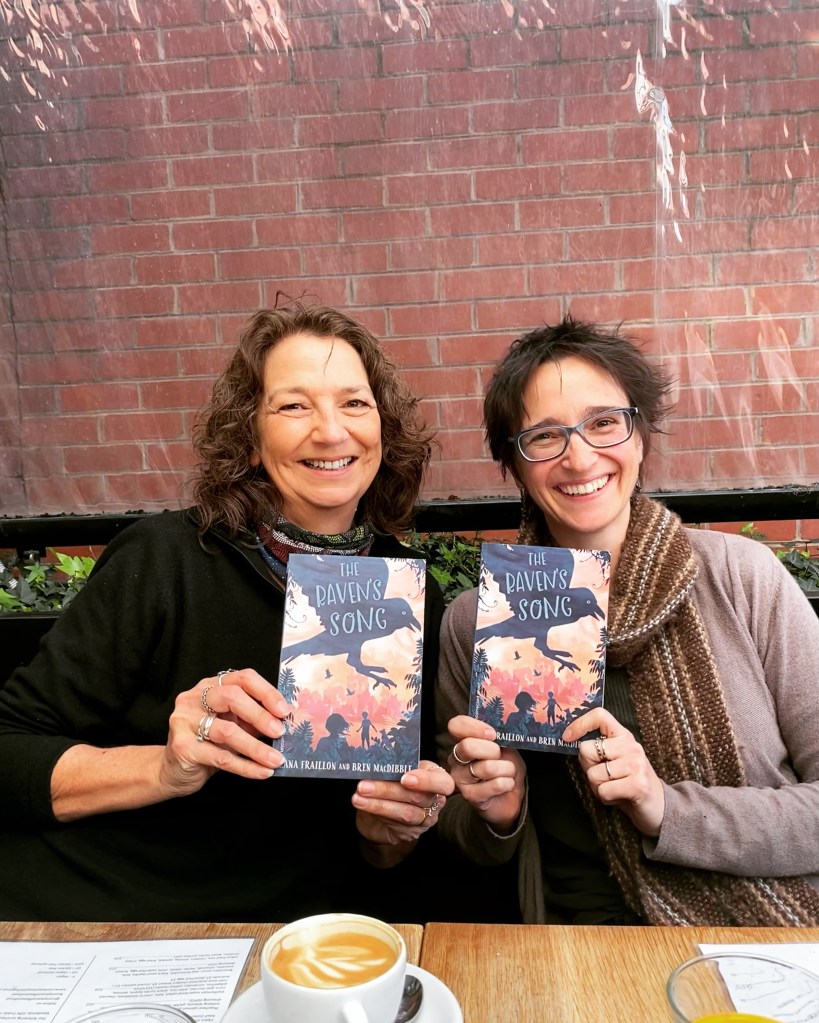

The Raven’s Song by Zana Fraillon & Bren MacDibble

Inside the CBCA Shortlist

Inside the 2023 CBCA Shortlist

The Raven’s Song by Zana Fraillon & Bren MacDibble (published by Allen & Unwin)

The Raven’s Song is shortlisted and is an Honour Book in the CBCA 2023 Book of the Year Younger Readers category.

On Writing The Raven’s Song:

Guest author post by Bren MacDibble for Joy in Books at PaperbarkWords

Bren MacDibble writes:

The Raven’s Song was a book that evolved over a couple of years as a result of an off-hand comment on Twitter back in August 2019. Zana was wanting some random ideas to get her brain firing and she liked my idea but not for what she was working on, and she said, ‘Co-author?’

I rarely put myself out there but I reminded her of her offer a few weeks later and so we kicked off this wild collaborative writing adventure dealing with a story set in a pollution and diseased ravaged world where future people tried to repair the world in the only way left to them.

Zana also was smitten with the whys and emotions of ancient child sacrifice and bog bodies and ravens as messengers through time so those ideas were also nibbling at our toes. What might sacrifice look like in a modern setting? What might we need to sacrifice to secure our future?

Little did we know a real pandemic was on our horizon and when Covid set in, we almost kicked the manuscript right into the bin! Who would want to read about a bird flu called Corvid when we now had Covid?! But we were so emotionally invested our carefully crafted characters and enjoying the process and wanting to figure out the outcomes for them. It was something to keep us writing through lockdown at the very least and so easy.

Writing collaboratively means always having someone who knows your book as well as you do to bounce ideas around with and we had so much fun. We couldn’t leave our manuscript unfinished even if completion was just for our own benefit. We adored the collaborative process. Two brains are so much better than one. To have someone cheering you on or pushing you to take something further or figure out the stumbling blocks while you’re in the writing process is rare.

Our book is set in a world 100 years in the future after the cities have fallen and the survivors live in secluded self-sufficient townships fenced off from the natural world, and didn’t we see the natural world spring back around the edges of cities fairly quickly when lockdown was on! I liked the idea of fencing the humans away from the natural world. The opposite of what we do now. My character lives in one of these townships honouring all things natural, but when she goes through the perimeter fence she finds a ruined city nearly on their border, of course being the inquisitive child she is, she has to explore it and things escalate from there.

Zana’s character lives just a few years from now during the last great pandemic just as that very same city becomes untenable. He’s the glue in our story, a sensitive child with an inherited ability to sense people through time, a skill he’s not altogether happy to have.

There was never a bog girl in our original bouncing around but when Zana came back with not only her character’s chapters but this whole new bog girl thread, it was like the story had stretched through thousands of years. A story as old as time. What does it mean to be a good ancestor? What did it mean to the ancients, what does it mean to the modern child and what does it mean to the future child? What impact do we have on our planet and how does that ripple through time?

There was definitely a feeling that we were caught up in a story bigger than both of us. And now it’s a published book, it and we have become part of the conversation about what modern people leave to the future. We’re very proud of that.

At its heart The Raven’s Song is the story of two children who get caught up in a wild adventure bigger than themselves much like Zana and I were. We hope that young readers get caught up in the strange lands and fun adventures our characters have and that also our book is a catalyst for thinking about our place in time and history and what we can do for future generations. We realise children often feel powerless and fearful when they hear about pollution and climate change but if enough small people do enough small things it’ll add up to big things. It’s the ultimate act of faith in humanity, I feel, to take small actions and trust others will too. We’d like to empower our young readers to hope and dream and take action.

The Raven’s Song at Allen & Unwin

My interview with Zana Fraillon & Phil Lesnie about The Curiosities at PaperbarkWords

*****

A SELECTION OF MY INTERVIEWS WITH BREN MACDIBBLE & ZANA FRAILLON AND REVIEWS OF THEIR BOOKS

My interview with Bren MacDibble about Across the Risen Sea and her other books

(from Magpies magazine September 2021 – reproduced with permission)

Across the Risen Sea by Bren MacDibble

“We live simply coz our folks learned that what people do can damage the planet … We salvage everything we need.” (Across the Risen Sea)

It is such a treat to speak to Bren MacDibble. I have been a great admirer of her books for children and young adults from How to Bee and In the Dark Spaces (written as Cally Black) onwards. She has a tilted imagination that conjures new perspectives on worlds that seem familiar but are enhanced and changed.

In my judge report for How to Bee, winner of the 2018 Patricia Wrightson Prize (NSW Literary Awards) I wrote:

In this fine dystopian novel set in a near future world, bees have been destroyed by poisons and children attempt to replace them by manually pollinating flowers to form fruit. Nine-year-old Peony is desperate to move up the hierarchy of farm-workers and become a ‘bee’. Her heart’s desire is threatened when Ma kidnaps her to work in the city for the ‘Urbs’. Once there she feels displaced after having been productive and valued.

Life in the country seems relatively idyllic, swayed by nature’s rhythms and cycles. Gramps, Peony and Magnolia had been content. Sensory descriptions evoke a soothing, fertile setting, balanced with a rustic vernacular to create a down-to-earth tone. In contrast, figurative language reveals the shock of a city stuck in a dirty mist and its raggy people. Peony’s unschooled, direct voice remains constant, bridging the structural changes of moving from country to city and back again: one of several cycles explored within this rich novel.

The characters are authentic and unsentimental: deliberately flawed to reveal degrees of self-interest, goodness and courage. Like a healthy colony of bees, young readers may appreciate that pride and perseverance in being part of a functioning, caring community is vital. Locally and globally, climate change and diminishing bee populations are of great concern and interest. How to Bee catches these issues in a skilled storyteller’s net, transforming them into a highly engaging literary work.

In my review of The Dog Runner for the Weekend Australian, I reflected that the “NZ-born author has an affinity with the Australian landscape. She sculpts it as familiar but unromanticised.”

Thank you for speaking to PaperbarkWords, Bren.

Thank you, Joy, for hosting me and all the lovely commentary you’ve made on my work for the last few years.

What are the ups and downsides of being known by two names?

The upside is that I’m not shocking younger MacDibble readers with works meant for a young adult audience because those are published under the name Cally Black. It backfires regularly when I turn up to events as one author and the books of the other are not on sale at the bookstall, and if teachers and librarians aren’t aware to help guide MacDibble readers towards Cally Black.

Which one is your real name and how did you choose the other?

I’d always been Bren MacDibble for my educational fiction aimed at very young readers and when I won the Ampersand prize Hardie Grant felt it was better to launch on a whole new name to distinguish from the younger books, and being aware a middle grade novel was very likely about to be picked up by Allen & Unwin. A conversation with marketing was had where I said I felt that Black was a name that was pretty much like Bloggs or Doe but specific to writers, a kind of placeholder name, and if we had a name that wasn’t a name like Calanthe (an orchid/witch) then that would help search engines pick out me, but marketing decided Calanthe felt fake and Cally would be better… and we all went along with Cally Black. Plucked at random! Also Mac and Dibble is a strange conglomeration of my maiden and married names thereby proving names don’t matter at all!

Do you feel you have a different persona depending on which name you’re using?

I feel like MacDibble has to be more gentle and parental but Black can rally at the world a little more. Be a little more aggressive. Maybe this is because of my audience’s age groups.

You seem to have been travelling around a great deal. Where are you based at the moment and how is it affecting your writing?

We bought a business in Kalbarri at the end of 2019 and we took it on early 2020 just in time for covid lockdown. This closure was followed by a boom when WA locked all its people inside its borders and the whole of Perth decided it wanted to go on holiday somewhere warm.

We love it here on the mid-west coast. The glorious turquoise Indian Ocean, the white sand, the massive red rocks, that winter only lasts a few weeks, that we are so far from the nearest city. It’s such a wonderful place to live. I can’t imagine living anywhere else right now, although we still have the bus so some trips are on the cards. I’m writing this from the bus parked in Perth for a couple of festivals right now. Can’t wait to leave the traffic behind!

Your books show your deep care and concern for our natural environment. Could you give an example from one (or more) of your novels?

How to Bee is set in a world post-insect loss, in particular the European Honey Bee. The Dog Runner has a back drop of poor land management and grass loss, and Across the Risen Sea is set in a post-sea level rising world.

I get frustrated that the information on how to do better is there, but change is slow. And when climate change feeds climate change, we don’t have time to go slow.

I see children take on these heavy issues and it’s difficult for them to find space or the words to vent their fears. They wonder if kids like themselves and their families might survive an environmental disaster, so my books are an exploration of that fear and yes, however changed, there’s family and love and survival in my books. I hope they empower young readers and give them a safe fictional space to think and talk about future environmental issues.

I got a Neilma Sidney Travel Grant to research The Dog Runner. In this book I kill off all grass with a fungus, initially I thought this would be just a grassless world with a famine happening but after visiting Graeme Hand at Stipa in Victoria who does research in the area of grassland regeneration and after reading Dark Emu by Bruce Pascoe I realised there’s a deeper issue running through any story of grass in Australia, and that is land management. In particular, the ignoring of thousands of years of grass cultivation and land management in the years prior to the introduction of European farming and the damage caused by the implementation of modern farming methods onto Australian land. It alarms me that the only people advising our farmers are the people who want to sell them fertilisers and other chemicals. Basically, if we don’t protect our soil and the mycorrhizal fungi in our soil it will continue to degrade, produce plants with poor nutritional value, and allow water to run off. kisstheground.com is a website that can far better explain the completely fascinating subject of soil!

Is it true to say that your novels champion the underdog? If so, could you give an example from one of your books?

It’s absolutely very true. We’re dealing with post disaster futures here, and as we see repeatedly that poor people are always affected so much more by disasters than others. People with money and insurances and family help can mitigate drastic changes to their lifestyles when disasters strike.

In How to Bee, Peony lives in a shack on an orchard and works on the orchard as a way to earn their life there, which is so much better than the streets where her family found themselves during famine times, and provides a poor but decent lifestyle for them.

The underdog situation I most enjoyed creating was Tamara’s in In the Dark Spaces. It came about as a result of spaceship design and corporate payment structure so it seemed natural. The outer ring of the space freighter she lives on spins at a speed that creates Earthlike gravity… but she lives on a ring inside that outer ring which doesn’t spin as fast, so she and the other lowly workers there don’t have enough gravity to maintain decent muscle mass, not only that, they are not paid enough by the shipping company to save money. So when they want to leave the employ of the shipping company, they have no money with which to start a new business and no ability to hold themselves upright for very long on a planet with decent gravity. They are in fact trapped in the employ of the shipping company being dragged further and further from planet Earth.

So many people find themselves caught in a similar situation, all their money goes on the basics. It’s an allegory for the working poor.

Many of your characters have a unique, idiosyncratic voice. Could you explain the style and from where it derives?

All my characters are from the future, none of them are educated and I think long and hard about the influences to their manner of speaking. Is it rough, is it multi-cultural, what slang have they created, is it influenced by anything around them? I also don’t want to alienate readers from other countries or leave anyone confused. I want to give hints of future lives and worlds and still have the language roll through the story without tripping the reader. Of course, it’s impossible to please everyone once you start corrupting a language but I do my best to make it feel natural and self-explanatory.

The base of most of the languages and manners of speaking I develop start off in a simplified rural US way of speaking. I feel like we’re all familiar with that due to TV, and that they are the readers least exposed to other ways of mashing English around as we do.

I love hearing English thoroughly corrupted and colourful manners of speaking. Such a robust language. The tones and fun of English from the deep south, New Orleans, etc. is glorious.

Your most recent novel for younger readers is Across the Risen Sea. What impact has publication during the thick of COVID had on the book?

Well it wasn’t launched. I could have zoomed a launch but honestly we were all getting a little zoomhausted by August of 2020 and adding to the noise of book launches seemed a bit daunting. So it slid quietly onto the shelves of Australia, New Zealand and the UK without so much as a bookmark waved.

To be honest, all my books entered the marketplace fairly quietly and have relied on word of mouth, teachers, librarians and shortlistings to build attention. Those elements were and are still available to me. I feel like Covid may have affected Across the Risen Sea a little less than other books or debut novels. Now it’s a CBCA Notable and it was a CILIP Carnegie nominee in the UK, so there’s still time for attention to build.

How to Bee arrived in North America at the same time, and has fared less well in a new market.

Settings across your novels vary and are always exciting in their originality and the strong mind-pictures they create. Where and when is this novel set and what puts the community at risk?

This novel is set in a post-sea level risen world in which rural areas have been abandoned by their government and have settled into peaceful hilltop island communities who self-govern and are strongly into environmental gentleness. Neoma and Jaguar two children of one of these communities are not only best friends, they plan to be the best fishing and salvage team on the whole of the inland sea, until a new government comes, bringing with it technology, old ideas, talk of impending threats and finally a mysterious death of one of their own. They take Jaguar to make the community pay and Neoma takes a boat far across the risen sea to fetch him back. They also have to solve the mystery of the dead body.

Could you introduce your major characters Neoma and Jaguar/Jag? Which of their traits most appeal to you?

Neoma is headstrong, physical, brave, a doer, not a thinker, a proud and fiercely loyal friend and family member. Jaguar is a thinker, a tinker, a collector of useful bits and pieces, a more cautious member of the team. It’s like Neoma allows him to be her conscience, her warning bell, and he allows her to be his motivation, his tester of things that might be unsafe and his planner of grand adventures.

I like that Neoma is physical, she gets the job done, she’s proud, protective and smaller kids look up to her. I like that she’s always pushing to be more independent and be the best.

Please tell us about their wonderfully named boat.

Neoma’s mother runs a quick and nimble sailing catamaran called Licorice Stix. It has two slim black hulls, a small cockpit, and a large trampoline net across the front half. It’s great for getting quickly out to the derelict towers to look for salvage and the net is good for carrying it back. Perhaps it’s the kind that was used for racing in the time before the risen sea, now it’s used for fishing and salvage.

I love your croc character. Could you tell us about it without spoilers?

I had in mind that with a warmer climate and vast brackish inland seas, crocodiles would thrive and be forced further south, and young crocs would be cruising the bays looking for their own territory. Of course, crocs don’t do well in the open sea far from land so I can’t imagine that any croc, once it finds a safe refuge somewhere like say on a boat, would be keen to get off if they couldn’t swim to land. Sometimes crocs just want to keep their heads down avoid confrontation, munch on free meals and wait until the time is right to swim for shore.

As in your other novels, your young people in Across the Risen Sea are brave and resourceful. How do you think we can help children gain more resilience, and also alleviate their fears and anxiety and protect them physically?

It’s hard to teach kids resilience. I feel it’s something they can only learn by doing. You can teach them about the monkey mind and how it will berate their every failure but they actively need to train their minds to recognise and argue against damaging self-talk, which means letting them do things independently, letting them have small failures and helping them cope with negative emotions.

The great outdoors is wonderful for that, building huts, playing in streams, climbing trees, getting from place to place, adventures with other children, expressing their emotions.

To feel resilient they have to have some degree of control over their environment and themselves. They need to feel like they can survive in the world without their parents stepping in constantly and that when they need their parents they can express themselves calmly and receive the help they need.

What symbols recur across some of your works?

I think the greatest symbol is poverty, and how those people are always affected disproportionately more, when ever any disaster happens, the rich/poor divide, and the natural world versus the created world, the industrial machine that has brought us to this environmental precipice is faltering as the world upon which it sits falters. Where do we go next? What’s a better way of living?

How has your writing changed or developed since How to Bee and In the Dark Spaces?

I think I am gaining more experience in how things are received by readers. I’m thinking more about what children are seeing in the world, and where they’re at emotionally.

Across the Risen Sea is lighter, than my previous books because there’s so much awful stuff going on right, and I want children to find comfort in reading as well as exploring a world with rising sea.

In which countries are your books being particularly well received and what is next for Bren MacDibble and Cally Black?

As well as Aus/NZ the UK are devouring Bren MacDibble’s books. Sadly no other country has snapped up Cally Black’s wild SF thriller yet. Maybe they’ll catch up soon.

Cally is putting the finishing touches on a quieter contemporary novel about a girl lost at sea and Bren MacDibble has teamed up with Zana Fraillon in a dual narrative middle grade novel that spans time and will give everyone something to get their teeth into with regard to environmental lessons through time and pandemics.

What have you read recently that you would like to recommend?

I recently read Lizard’s Tale by Weng Wai Chan, which was the winner of the junior novel in the New Zealand Book Prize last year, thinking I was picking up an historical novel, and it was also a wild rollicking spy story, so that was great. I finally got to Road to Winter by Mark Smith as well, and really enjoyed that. I love how the kid still goes surfing even though everyone in the whole town is gone, and the sense of menace from the roaming packs of people is so terrifying!

How can your readers contact you?

Please leave me a message on my website or to @macdibble on Twitter.

Thank you for your responses, Bren, and most particularly for your fine, original novels. Across the Risen Sea is up there with your best work and I hope it reaches the acclaim and readership it deserves.

Thank you for your support.

******

My reviews of books by Bren MacDibble and Zana Fraillon in The Australian

My review of The Dog Runner by Bren MacDibble in The Australian April 2019 (I have included the full 4-book review for those who are interested. Scroll down for The Dog Runner)

Entering another world

- By JOY LAWN

- UPDATED 12:23PM APRIL 16, 2019, FIRST PUBLISHED AT 12:00AM APRIL 13, 2019

Many novels for young adults are set in a difficult, even violent world, real or speculative. A fraught coming-of-age experience, one that is nonetheless enfolded in hope, is a common theme.

Catch a Falling Star (Walker Books, 256pp, $17.99) by Meg McKinlay, a 2016 Prime Minister’s Literary Award winner for A Single Stone, is one of three middle-fiction novels for younger teens under review today.

Frankie’s father shared his love of astronomy with his daughter before he disappeared in a plane crash in 1973. This coincided with the launch of the Skylab space station, which he had planned to document in a scrapbook with his son Newt (named after Isaac Newton).

The story jumps to 1979, when Skylab is about to return to Earth. In Western Australia, Frankie and her classmates anticipate the descent, planning where they will shelter and fantasising about being astronauts.

Frankie cannot bear to reveal her childhood wish to be an astronomer because of her unresolved grief. Newt is now eight and a precocious scientist. He finds their father’s notes in the broken-down shed that was their Space Shack. He tracks Skylab’s orbit obsessively and merges scientific facts with the Greek Callisto myth that their father is a bear in the stars and will return with Skylab. Frankie also longs to believe in magical stories.

Their mother works long hours as a nurse and leaves Frankie with too much responsibility, particularly looking after Newt. She thinks that Frankie is fine. The author, who is also a poet, subtly explores the alternative meaning of “fine” to depict Frankie’s fine writing and thinking. She also contrasts the broken bone of a young patient looked after by Frankie’s mum with Frankie’s broken family.

Frankie thinks, “I just want my mum for once. I want her here, with us … and not spinning out there in the dark somewhere, in her steady, untouchable orbit.”

Media reports on Skylab’s re-entry change in tone as it becomes a threat. “Tumble” becomes “plummet”. The stars Frankie loved now sicken her but, because her friend’s mother told Newt that their father is a star, he tries to reach him.

Frankie feels that she must catch both him and their father as they fall from the stars.

Frankie’s class is reading Colin Thiele’s Storm Boy and she understands the book “isn’t about a pelican. It’s about losing something important, something that feels like part of your heart. It’s about things falling from the sky while all you can do is watch. About not being able to save the thing you love no matter how fast you run, no matter how much you hope.”

The Slightly Alarming Tale of the Whispering Wars, by award-winning author Jaclyn Moriarty (Allen & Unwin, 528pp, $22.99), is a stand-alone companion to her 2017 book The Extremely Inconvenient Adventures of Bronte Mettlestone.

It is set in the same fantasy world, and Bronte and her friend Alejandro reappear at strategic times to help the protagonists, Findlay of the Orphanage School and Honey Bee from prestigious Brathelthwaite School solve the mystery of the missing children.

Findlay and Honey Bee are good athletes who meet at the Spindrift Tournament. They share the narration, often with different and quarrelsome perspectives on the same event. The structure is sophisticated, with parts told retrospectively.

The writing is whimsical, imaginative and humorous, with taunting acts of rivalry between the schools and magical inclusions such as Radish Gnomes, Faeries and dragons. It is voiced by real-sounding children who address the reader and annoy and care for each other.

In the story, Whisperers are stealing children from the town of Spindrift and across the Kingdoms and Empires, and taking them to the impenetrable Whispering Kingdom. Findlay, Honey Bee and some of their friends allow themselves to be kidnapped so they can rescue the children.

Once there, they are as powerless as the other captives and have to work in the mines plucking strands of thread from rock.

Weighty themes — child slavery, distrust of those who are different, war, expedient alliances, vilification, internment behind barbed wire and unjust treatment of the poor and refugees — are told lightly, yet with impact.

Ultimately, though, this exceptional novel leaves us with a sense of the power and compassion of young people, and their ability to change the world when they recognise their own strengths and draw on the love of their family and friends.

Bren MacDibble is the author of the multi-awarded 2017 novel How to Bee. Her new dystopia, The Dog Runner (Allen & Unwin, 248pp, $16.99), echoes Cormac McCarthy’s The Road — but with the help of dogs.

Most of the world is starving because a red fungus has destroyed the crops. Food is scarce because it is dependent on plants and grass: bread, rice, corn, meat and dairy products. The government has stopped distributing food packages and people are stealing or trading on the black market.

Ella is 10. Her mother, who helped maintain the power grid, has been missing for eight months. Ella’s father goes in search of her and also doesn’t return. Ella and Emery, her 14-year-old part-Aboriginal half-brother, know it’s time to leave the city.

They want to head to a farm owned by Emery’s mother and grandfather. Emery exchanges Ella’s precious tin of Anzac biscuits for a cart, dog harnesses and two huskies to help lead-dog Maroochy and their two other malamutes pull the sled on wheels.

They escape the city on moonlit, “white ribbon” bike paths, then cross paddocks, creeks, gullies and a rocky hillside through red dust. The New Zealand-born author has an affinity with the Australian landscape. She sculpts it as familiar but unromanticised.

They encounter the vulnerable, the kind — and gun-toting predators on electric motorbikes. Ella draws on her quick wits and endurance to keep the tribe safe. She learns that in an upside-down world, survivors must “walk on their heads” and think differently.

The writing in this cautionary but hopeful tale is pared and sparse. It is told in an idiosyncratic style (“my stomach is aching of empty”) that brings the characters and setting to life.

For older readers, Angie Thomas’s two acclaimed YA novels The Hate U Give (released as a movie this year) and On the Come Up (Walker Books, 448pp, $17.99) are authentic, potent representations of a contemporary African-American ghetto experience. They are set in the fictitious gang-controlled, drug-fuelled suburb of Garden Heights, narrated by teen girls and steeped in distinctive, cadenced slang.

The community in On the Come Up is reeling and rioting after a police shooting of a young unarmed man. Security guards at 16-year-old Bri’s school are now targeting the “black and Latinx kids”. Bri is caught bringing contraband — candy — to school and is thrown to the ground and handcuffed.

Bri is like her father: smart-mouthed and hot headed. He was an underground rap legend who was murdered when Bri was four. Her mother, a former junkie, is trying to keep food on the table. Her aunt is a drug-dealer.

Bri feels invisible, powerless and “a hoodlum from a bunch of nothing” until she has the chance to rap in a freestyle battle. This and the other rap scenes are electrifying.

Bri composes on the spot, turning her aggression and angst into a rhythmic flow of sounds and words. Her song goes viral and she becomes neighbourhood royalty. In “the Garden, we make our own heroes”.

On the Come Up is a brilliant, unflinching expose of racism and violence, and a story about how strong-minded individuals and families in tough, disadvantaged societies can survive and save each other. Told in pain, yet with warmth and love, this story is throbbingly real.

Former Australian children’s laureate Jackie French writes across genres and eras. Just a Girl (HarperCollins, 256pp, $16.99) is set mainly in Judea in AD71, when the Roman army destroys a Jewish village.

Grandmother Rabba orders young narrator Judith to carry her to a cave that the women have secretly stocked with food. Judith also rescues her younger sister, Baratha, but witnesses the horrific death of her mother and capture of her older sisters.

Judith has been a shepherd since the menfolk went to war so is skilled at hunting with a slingshot. When threatened by a Roman, she hits him in the forehead with a stone and believes she has killed him. Rabba instructs her to honour the dead by burying him, but she finds him alive, although badly injured.

Caius is a scribe-slave, now freed because the Romans abandoned him. He helps the cave-dwellers survive cold, flood and a wolf attack. His and Judith’s questions about Rabba’s past friendship with a girl she calls Maryiam and her son Joshua prompt Rabba to gradually reveal fragments of the Christmas and Easter stories.

The author draws on her expertise in researching, retelling and linking historical events to outline the tale of Maryiam/Mary, whom she describes as a “dimly seen historical figure”.

French’s writing evokes the village “huddled between lion-coloured hills”, the dank cave and the routine of scavenging and cooking.

Themes of war and its aftermath, slaves, refugees and female worth are both time-specific and universal. Judith learns that, like Maryiam and Rabba, she is never only “just a girl”. She is curious, intelligent and strong. Despite its violent setting and time, this is ultimately a gentle tale of kindness, joy and hope.

Joy Lawn is a reviewer of young adult fiction and children’s books.

*****

My review of The Bone Sparrow by Zana Fraillon in The Australian September 2016 (I have included the full 5-book review for those who are interested.)

Young adult fiction: Fraillon; Herrick; Jonsberg; Griffin; Bradley

By JOY LAWN

12:00AM SEPTEMBER 3, 2016

Family is critically important for the healthy development of children and young adults. Those who are unsupported or abandoned are vulnerable. Those who have loving families, of which even the best are imperfect, have physical and emotional shelter.

Melbourne-based Zana Fraillon’s The Bone Sparrow (Hachette, 234pp, $19.99) is longlisted for the international Guardian children’s fiction prize. Fraillon has crafted a unique voice in her exquisitely written universal refugee tale.

Subhi’s family is from Burma, now Myanmar. Its Rohingya people were told they didn’t exist, and were tortured and killed as they tried to leave their country. They fear they have been forgotten by the world.

Subhi has grown up in an isolated Australian detention centre with his ailing mother, older sister and friend Eli, the only survivor of a truckload of passengers, who is now at risk of being sent overseas. The detainees aren’t medicated and good food is provided only when people from Human Rights Watch visit. Newcomers to the camp quickly lose their optimism, and lip-sewing and hunger strikes escalate.

In a surreal encounter redolent of John Boyne’s The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, Jimmie, an illiterate girl who carries a book written by her mother, now dead, finds a weakness in the fence and discovers Subhi. He loves to draw and read and, while Jimmie tells him about the “Outside”, he unravels the serendipitous story of her ancestors. There are many parallels in their dual narratives: birds, rats, sickness and the stories that are essential to preserve memories, though Subhi figuratively loses his story after one horrific death and betrayal too many. He wishes he hadn’t reached an age when he knows the truth about his life because understanding makes it worse.

Subhi is waiting for his father who seems to be sending him treasures on the Night Sea. The author layers metaphorical images of the red dirt lapping at the tent, the family photo and other treasures half buried in the sand, and the whale and other Night Creatures that appear to Subhi. Story as a “whispered memory” is entwined in the deep song of the imagined sea and the entrancing stars and lights.

The bone sparrow is a potent symbol from both Jimmie and Subhi’s heritage. Is the sparrow a harbinger of death or a symbol of change and hope in this exalted, flawless book?

The mullet fish is the recurring motif of Blue Mountains author Steven Herrick’s Another Night in Mullet Town (UQP, 224pp, $19.95). Herrick is Australia’s premier verse novelist for children and young adults with highlights that include The Simple Gift and The Spangled Drongo. He has spearheaded this form to capture and portray realistic youthful voices in a poetic yet accessible and colloquial style.

In the lakeside town of Coraki, Manx describes himself as a mullet cruising in the shallows when he should be tackling the ocean. But he knows that ugly bull sharks have been let loose in the lake and they eat more than their share of the fish.

Manx looks older than the other 16-year-olds in the community and buys their beer. A drug and drinking culture takes place between the sand hills and lakeside pier. Manx thinks he and best mate Jonah, our narrator, “drag down the price of everything we touch”.

Jonah’s parents are fighting. His father is a sweat-stained, big-drinking truckie and his mother, once the prettiest girl in the town, works in the filleting line at the fish factory. They both love Jonah but decide to separate.

Jonah is handsome and attracted to Ella but too shy to speak until a deliberately awkward scene where he frames three-word sentences: “Ella reads quietly”, “Ella smiles imperceptibly”. Their relationship then somehow ignites.

A social and wealth divide is growing between the locals in their rundown houses on the only coastal road without a view and beach with a rip and the weekenders in their mansions. The developers have paid out the council and lured tourists with espressos. Through skirmishes and charges of graffiti, the boys protect each other: “We trust mullet with mullet / no matter what.” Fishing is the time they communicate, absorbed in a shared ritual.

Darwin author Barry Jonsberg also recognises the connection between males who share experiences without looking at each other. In Game Theory (Allen & Unwin, 320pp, $19.99), maths whiz Jamie’s best friend is overweight Gutless, who is so obsessed by slaughter video games he urinates into bottles to avoid leaving his festering room. Jamie isn’t so reclusive. He has friends at school but can talk most honestly to Gutless.

Jamie’s family is polarised by their different personalities. His parents do their best but his father seems useless and clearly resents his wife. His younger sister Phoebe is innocent and they have an affectionate relationship, but older sister Summerlee despises most of the family. When she wins Lotto after taking Jamie’s advice on possible numbers, she becomes even more toxic and is arrested for trashing a hotel room and other offences.

When Jamie and Phoebe are at the supermarket, where Summerlee previously had sprayed her boss with Coke, Phoebe disappears. Has she been kidnapped because of Summerlee’s new wealth?

The story is humorous but also becomes an exciting thriller when Jamie uses his mathematical knowledge of game theory to predict how the kidnapper may think and react. Jamie tries to change the balance of power by not following the rules and disorienting him. When the kidnapper first calls, Jamie audaciously tells him to phone back later because he’s busy. He also observes that the kidnapper “likes the juxtaposition of articulate vocabulary like ‘sensibilities’ with slang like ‘slut’ ”. As a mathematician, Jamie isn’t comfortable with narrative though he does use game theory to invent violent stories for Phoebe.

In New Yorker Paul Griffin’s luminous, empathetic novel When Friendship Followed Me Home (Text Publishing, 256pp, $16.99), Ben loves stories and books. He particularly enjoys sci-fi and believes “some books change the way you see the world, and then there’s the one that changes the way you breathe”.

Ben has had an uprooted life. He has been in foster care since birth, unable to find a permanent home because drug traces were discovered in his blood, making potential families wary. He is a hardworking, honourable though displaced boy who is finally adopted by his speech pathologist. They have a wonderful two years together before she unexpectedly dies, leaving him adrift and at risk once more.

He is drawn to the warm school librarian and finds shelter and escape in the library, where he also meets her daughter who looks like a rainbow with bright clothes and multicoloured wigs. Halley has cancer and their friendship, like the books and story they devise together, create perfect moments of light and hope.

The elusive magic of nearby Luna Park and Coney Island is reflected in the illusions of Halley’s magician father. Halley urges Ben to transform his bad experiences into treasure and, even when he is forced to sell his fine book collection, he tries to heal the lives of others.

Love springs from new sources, including stray dog Flip, who Ben trains as a reading therapy dog. Flip becomes successful at encouraging children to read.

The War That Changed My Life (Text Publishing, 316pp, $16.99) by American author Kimberly Brubaker Bradley is a Newbery Honor book. It is an inimitable, robust, yet lyrically written bildungsroman. Its gentle humour is poignant and heartwarming.

Even though she may be 10, Ada cannot read. As a “cripple”, she isn’t allowed to disgrace her ignorant, vicious mother by leaving her room. During World War II, Ada secretly teaches herself to walk, even though the pain of her untreated clubfoot is excruciating, so that she can leave London with other young evacuees. Much of her childhood has been spent locked in the cabinet under the sink so she is amazed by the outside world. She wonders at grass but is scared when leaves change colour and fall.

Ada and her younger brother Jamie are not chosen by any of the Kent foster families and are forced on to Miss Susan Smith, who tells them that she isn’t nice and doesn’t want them. However, she does provide food and clothes and their first bath, bedsheets, books and Christmas presents. Ada even teaches herself to ride and eventually learns to read and write.

She is angered and stunted by the realisation that this new, golden life is temporary. Even though there is rationing, raids and bombs, and Ada helps care for wounded soldiers, she is saved and set free by this war. Susan nurtures the children, but when she tells them that they have saved her life Ada feels something unfamiliar: “It felt like the ocean, like sunlight, like horses. Like love. I searched my mind and found the name for it. Joy.” Love can enable a deprived childhood to blossom.

*****

My review of The Ones That Disappeared by Zana Fraillon in The Australian August 2017 (I have included the full 4-book review for those who are interested. Scroll down for The Ones That Disappeared)

The Australian

Fleeing the fear and loathing

How young people respond to trauma and being trapped is explored in five new novels by Australian writers.

By JOY LAWN

Young Adult Fiction

From Review

August 19, 2017

Five new Australian novels explore young people’s response to trauma and being trapped. Some characters are stuck in time and place, others are victims of grief and persecution.

Ballad for a Mad Girl (Text Publishing,320pp, $19.99) is South Australian Vikki Wakefield’s fourth novel. It is a tightly plotted thriller and murder ballad with supernatural elements.

Senior students, “Swampies” from Swanston Public and “Hearts” from Sacred Heart Private School, have a history of crashing parties and feuding. Extreme prankster, Grace Foley, expects to keep her record on the “pipe challenge”, a tightrope-like crossing over the quarry where Hannah Holt, murdered years ago by William Dean, is rumoured to be buried.

Grace liked being scared, “When I’m standing in the middle of that pipe, knowing that something terrible happened here, knowing that there’s only air between me and death, I feel it: life is sharper, brighter, more intense. It’s a delicious kind of fear.” But on this night, the headlights are turned off, things are thrown at her, fear takes hold and she freezes.

When Grace was very young she scooped up the loners at school, forming a group of six chosen friends. They have tried to support her since her mother died two years before the pipe challenge but Grace isn’t listening. She’s always angry, turning her grief and fear into bravado. She worries that she might be going slightly mad, is sensing cracks between worlds and feels that she is carrying the weight of terrible histories.

Grace draws Hannah Holt subconsciously in Art class before seeing her as an apparition in her bedroom. It seems that Hannah wants Grace to discover her fate. As Grace follows Hannah’s trail, her health deteriorates and she wonders who she is becoming. The veil between reality and unreality is rupturing. People believe her when she’s lying, but not when she’s telling the truth. Her friends are moving on, “… you’re making no attempt to catch us. It’s like you only run if you’re in the lead.”

Gabrielle Tozer transposes her own youthful feelings of uncertainty, grief and heartache onto her characters in Remind Me How This Ends (HarperCollins, 352pp, $17.99). Milo Dark has just finished school but his friends and girlfriend have moved on to new adventures, leaving him behind in small-town Durnan. Milo and Sal were voted “most likely to get married” but Sal doesn’t seem to be missing him at her university in Canberra. Milo is adrift and has “no idea how I missed the memo everyone else got to get their lives together.”

At school, he was carried along in a slipstream rather than making his own decisions. His friends organised his relationship with Sal in Year 11 and their bond only deepened because she misheard his mumbled, “Ohhh, you,” as “I love you”. Much of the wry humour derives from Milo’s hopelessness and his older brother’s obnoxiousness.

His family own The Little Bookshop, a tired store where Milo and Trent work. While day-dreaming there about his lacklustre life, Milo is interrupted by Layla, his childhood, treehouse-sharing friend. She’s back in town after five years away. Even though Milo had become a “discoloured memory with blurred edges and a washed-out palette”, seeing him brings back Layla’s acute memories of their past and accentuates her unending grief about her mother’s death. She is now on the wrong side of town, living with a drug-dealer and even more lost than Milo.

The Secret Science of Magic (Hardie Grant Egmont, 328pp, $19.99) is the third original, heart-warming story from Melissa Keil. She avoids pigeonholing her characters and issues; here exploring diverse personalities and intelligences whilst subtly touching on race.

Year 12 students, Sophia and Joshua, share the narrative. Sophia is a maths genius with an eidetic (photographic) memory. She seems to be at the higher-end of the autism spectrum. People have always tried to “fix” her, so she’s unsure how to be normal and has learned to be silent rather than embarrass herself. She’s awkward but not shy, needs space, loves Doctor Who and can quote from Game of Thrones.

Joshua barely speaks at school. He is remarkable for his height and hiding behind his messy hair; his magic tricks and his long-standing but unnoticed interest in Sophia, kindled because she sees magic in maths. Raj describes Josh as a “reject-from-Slytherin type”. He can’t focus on things that don’t interest him, so his academic studies are faltering. Outside school, though, he is a different person; he could never be overlooked and stands out “like a cosmic spotlight is following him”. He is friends with Camilla and Sam, who starred in Keil’s first novel, Life in Outer Space.

Josh makes his move with magic tricks, leaving a Two of Hearts playing-card in Sophia’s pencil case. He progresses to the grand romantic gesture of a flaming paper rose and screens Doctor Who Christmas on the vintage projector in Biology. Sophia starts to notice Josh “like a nebulous element in the universe that has suddenly become perceptible” but mistakes her symptoms of love for illness. He is encouraged by her willingness “to meander down our weird conversational rabbit holes” but is always aware of timing, the magician’s fundamental tool, as he pursues the secret science of magic.

Young Columba is named after a dove. Her world seems safe but WWII encroaches in Ursula Dubosarsky’s The Blue Cat (Allen & Unwin,180pp, $19.99). Dubosarsky is a highly-awarded author, acclaimed for The Golden Day and The Red Shoe, about the Petrov Affair. She unfolds Australian history from the viewpoint of a naïve, but perceptive, child; using both vulnerability and danger to jut a dreamy uneasiness over Sydney’s bright harbour light. She also builds atmosphere by overlaying newspaper excerpts and photographs.

Innocent childhood games of hopscotch, jacks and skipping; and school traditions of marching in line, saluting the flag and saying the Lord’s Prayer, are menaced by the underlying threat of the local Strangler, who attempted to choke a woman during the blackout. The fall of Singapore and bombing of Darwin also loom.

The headmaster declares that Australia is a refuge for new boy, Ellery, who has come by ship from Europe. “Ellery is different to the other boys … You must remember that when you see him, and be kind.” Imaginative Columba only notices that he is clean, small and white. She thinks his difference must be inside, “like a secret treasure hidden in a garden”.

A blue cat also appears and disappears, a possible metaphor for Ellery. The children slip away from their swimming lesson near the Harbour Bridge to follow the cat into Luna Park. Surreal images from Columba’s dreams of Sleeping Beauty merge with the heightened cacophony of Coney Island.

After Ellery gives Columba his book and watch, he vanishes inside the spinning wooden barrel. Columba’s world then darkens, a bell rings, “the hands of Ellery’s watch ticked in time with my pulse … and Sleeping Beauty’s face was as still as waxwork, a statue of stone staring with blank eyes”. New and old fairy-tales materialise in this allusive, finely-crafted work.

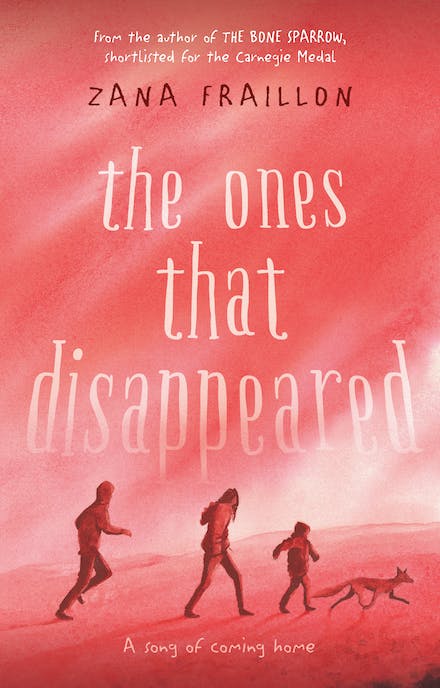

The Bone Sparrow (2016) by Zana Fraillon is set in an Australian detention centre and is currently being honoured with literary awards here and around the world. Fraillon has followed this with another important novel, The Ones That Disappeared (Lothian Children’s Books,256pp, $19.99) about trafficked children. They are “the ones that disappeared”.

The harrowing plot follows eleven-year-old Ezra, Miran and younger Isa who are tattooed and incarcerated by the powerful Snakeskin gang. They must tend marijuana plants in a basement in payment for their possible future release. They are bashed and threatened but unnoticed by those leading normal lives outside the brown brick house with a Neighbourhood Watch sign.

Miran tells them Tomorrow Stories which always begin, “One night … we will stand in the wild, and the river will lead us home. We will be fine and happy, and that is when our living will begin.”

When they try to escape from the shocking aftermath of a fire, Miran sacrifices himself so that the others can flee. He becomes the narrator for a time, enabling us to experience the insidious attempts on his life in a place where he should be safe. Other voices lead us forward into the unpredictable plot, but they always return to Ezra, the speaker for the dead and living, and her burning hope to find freedom for them all.

Fraillon uses images and symbols of birds, the river and Riverman, an elusive but benign figure created from clay. Her writing is dense and poetic, exquisitely searing but ultimately sparing us from despair with perfectly tuned magic realism, vignettes of human goodness and hope.

The horrifying reality of this tale is that there are “more children enslaved right now than the entire child populations of Australia, New Zealand, Scotland and Wales”. Fraillon uses the powerful mode of story as a cry for us to raise our voices for change.

*****

One thought on “The Raven’s Song by Zana Fraillon & Bren MacDibble”