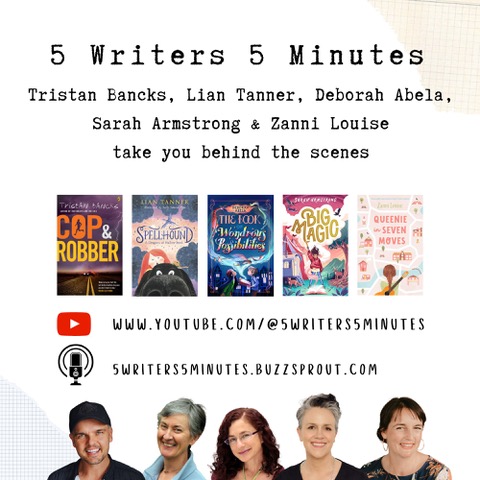

5 Writers 5 Minutes

Guest author post by Lian Tanner on behalf of the Ubers, the Uber-Talented Crit Group for Joy in Books at PaperbarkWords blog

Lian Tanner writes

Two years ago, in the middle of the Covid lockdowns, I received an intriguing email from author Deborah Abela.

‘I’ve wanted to be in a critique group for ages,’ she wrote, ‘with people I respect and admire and whose work I love. That’s you.’

How could I say no to such flattery? Next thing I knew I was a member of the humbly-named Uber-Talented Crit Group, along with Deb, Tristan Bancks and Zanni Louise. A little later, Sarah Armstrong joined us.

Deb proposed that we meet once a month, sending a few chapters of our work-in-progress to each other beforehand, and chatting about any project/problem we needed help with.

As someone who habitually huddled protectively over my early drafts and snarled at anyone who got too close, showing those drafts to the group was a challenge at first. But it was worth it. We’re all passionate about children’s books, and bring a huge amount of collective knowledge to the topic. Zanni and Sarah might be new to middle grade, but they come to it as experienced authors.

And the support is phenomenal, in good times and bad. When Spellhound was launched, earlier this year, a large bunch of flowers arrived on my doorstep. When Zanni’s dog was run over, she got flowers, too. When Deb was stuck in lockdown, the rest of us sent chocolate and books to cheer her up.

But there’s also informed and intelligent criticism. I spent last year working on Fledgewitch, the follow-up to Spellhound,and somewhere along the way I fell into the trap of trying to be too clever with the beginning. I clung to that beginning for a couple of meetings, trying to justify it, but when four experienced authors tell you kindly but firmly that they’re confused, and don’t understand what’s happening, it’s time to listen.

It’s significant that we’ve never had a meeting without all five of us present. Zanni has dialled in from Austria, the Netherlands and Lightning Ridge. Deb once joined us from the passenger seat of a storm-drenched car, on her way to Newcastle. Sarah attended a whole meeting from beside her mum’s hospital bed, with occasional breaks to consult with doctors.

In April this year, we started talking about a podcast that teachers could use in the classroom. We’re all busy people, so we needed to find a way of doing it without adding hugely to our workload.

That’s when we came up with the idea of something short and sharp, with each of us giving our take on a particular topic. (The words ‘Brady Bunch’ and ‘Famous Five’ may have been mentioned.)

We wanted it to be a genuine look at things we discuss in the group, like getting started on a new story, where we find inspiration and how we use research. We wanted to show how authors do it, and how we’ve used it in our own books.

And so ‘5 writers 5 minutes’ was born, as a weekly podcast and YouTube video. It’s designed to take kids behind the scenes, to give them writing and editing secrets, to offer tips on how to write their own stories.

We all agree that being a member of the Ubers has made us better writers. Now we want to share the joy.

Lian Tanner

(and I write more about Author Support/Critique groups in my editorial in Magpies magazine September 2023)

Deborah Abela at PaperbarkWords

Tristan Bancks at PaperbarkWords (and elsewhere on the blog)

Sarah Armstrong at PaperbarkWords

Zanni Louise at PaperbarkWords

*****

My interview with Lian Tanner for Magpies magazine about Ella and the Ocean

(reproduced with permission)

Ella and the Ocean by Lian Tanner, illustrated by Jonathan Bentley

Thank you for speaking to Magpies magazine, Lian.

Your stunning picture book Ella and the Ocean (Allen & Unwin) has deservedly won the Patricia Wrightson Prize in the 2020 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. It is an exceptional work in traditional picture book form.

(Read my judge report at the end of this interview)

How surprised/excited were you to win?

I was incredibly excited. We both were. When we got the news, Jonathan and I were sending each other emails that basically consisted of ‘AAAAAAAAAARGH!’ Plus we were told about it more than three weeks before the awards were announced, and weren’t allowed to tell anyone, which was both incredibly hard and wonderfully delicious. It was like having this little golden secret that I carried around in my hand, and every now and again I’d open my fingers and peep at it, and burst out laughing with the sheer delight of it.

Not sure how to link to my particular speech except through twitter – there doesn’t seem to be a youtube link available. https://twitter.com/statelibrarynsw/status/1254346542149799936

What does winning the award mean for the book and also your careers?

Winning this award would be amazing at any time, but in this particular year when we’ve all been sequestered away and not able to do any of the usual promotional things, it has been particularly important. It keeps the book in the public eye, it makes people take a second look at it. And I guess it makes people take a second look at me as an author, too. It’s a splendid thing to have on my CV and on my mantelpiece! Plus wonderfully good for the ego, which is also important because being a writer is such an up-to-the-heights-and-down-to-the-depths sort of thing.

Our judging panel – Maxine Beneba Clarke, Alex Wharton and I – were deeply touched by the book. We all experienced a strong visceral response to it. How have you represented drought and family with such power and truth?

To be honest, I’m not sure. I started writing this book more than twelve years ago, but back then I didn’t know enough about picture books to make it work, so I put it aside for quite a few years. I suspect that ideas that you put aside like that sometimes have more weight and complexity than ideas that come easily. They cook while you’re away from them. They grow wings while they’re tucked up in the darkness waiting for you to come back. So by the time you return to them, and start reworking them, there’s so much more happening than when you started.

Plus of course every writer brings so much of themselves and their own history to every story, and my mother was a farmer’s daughter from the mallee, so the hardships of farming and drought were something my brothers and I were very familiar with from her stories.

How did you work together or independently to further the story?

This is one of the things that amazes me about the book. It was a collaboration of the work rather than the individuals, in that Jonathan and I didn’t even speak by email until he had finished the illustrations. He had a couple of questions that he passed through my publisher, but other than that, we had no communication at all. And in a way, I think that also added to the richness and depth of the story. Jonathan was able to bring his own wonderfully vivid dreaming to it, without me interfering, or trying to influence him to take a particular direction.

How did you create your consummate cyclic structure in words and pictures?

I love cyclic structures, whether in novels or picture books – there’s something deeply satisfying about them. I also love rhythm, particularly in a book that’s going to be read aloud; the small rhythms of words and sentences, and the bigger rhythms of structure. The story of someone leaving home, being changed in some way by their experiences in the outside world, and coming back home again to see it with new eyes, has been told for centuries, and we never seem to get sick of it – perhaps because it rings so true, and so many of us have experienced it. That particular structure wasn’t there in the early drafts of Ella, but as soon as I found it I knew it was central to the story.

Further details are noticed on multiple readings. For example, could you tell us about your symbolic use of water?

I try really hard not to think about symbolism while I’m writing, because otherwise it can get heavy-handed. And if I start to push one thing, I can easily miss something more interesting. Whereas if I leave it up to my subconscious mind to sneak things in, almost behind my back, it seems to work much better – the layers of meaning become more subtle and more genuine.

When I first started writing Ella, it was more about the power of imagination, and the ocean was really just the vehicle for showing that. But somewhere along the line, I started thinking about how for so many adults, the ocean is one of the few places where we still allow ourselves to play like little kids. And then the red red dirt cropped up, and the question of drought vs ocean was right there in front of me, and the effect that each of them might have on the family and their dreams.

But even then, I deliberately didn’t think about the symbolism in explicit terms. I just wanted to get the words right. To tell the story in the best way possible.

Lian, the characters’ words about the ocean are repeated in slightly different ways. For example, Mum describes the ocean as “blue and shiny like your hair ribbon” but doesn’t want to bother travelling to see it, “It’ll be tangled and knotted like your blue hair ribbon.” It is a lovely idea. How did this concept evolve and how difficult was it to execute?

As I said, the book started off being about imagination, and how a child who had never seen the ocean would picture it. I thought her parents might try to relate it to something she was familiar with, which is how the blue hair ribbon came into it. But being a very literal child, Ella wonders if the ocean will then have the same qualities as her hair ribbon, which gets tangled and knotted when the wind blows.

As the story changed, and became more about drought and resilience and the importance of dreams, it made sense to start relating the ocean to other parts of Ella’s world, like the wild horses, and the land between here and the hills. And that led to the idea that those same things could be a way of talking about the harshness of the environment, and the effect that harshness has on the people struggling to farm it.

Were there any technical difficulties that either of you had to solve while composing the work?

Working out how many words I could leave out was the big learning process for me. I did a lot of drafts, and most of them were cutting down on the words, trying to find the poetry that lay at the heart of it. And finding the repetition without adding more words than necessary.

In some ways it was a lot like writing a play, where you have to leave room for the actor, and all the skills and emotions that they bring to the part. So, because you’re leaving room for the illustrator, you don’t put nearly as much on the page as you would with a novel, for example. It took me a long time to get that right.

Of what are you most proud in Ella and the Ocean?

It’s my first picture book, so I’m pretty well busting with pride about the whole thing. But I think the bit of it I love most – words and illustration – is the double page where they are floating in the ocean. And smiling. ‘And all their broken dreams were washed away.’

What do you hope young readers understand or remember from this book?

So many things! The harsh beauty of the red dirt country. The struggle of the people who farm it. The importance of play and imagination, for both children and adults. The awareness that dreams are important, and if we can, we should follow them to see where they lead.

Could you tell us about some of your other books?

I wrote three middle grade fantasy adventure trilogies before I wrote Ella; the Keepers trilogy (which has been translated into eleven languages, and won two Aurealis awards for children’s fiction), the Hidden series, and the Rogues trilogy.

I’ve gone in a different direction with my next book, which is coming out in August. It’s a contemporary middle grade detective story called A Clue for Clara, and it’s the story of a chook who desperately wants to be a detective.

What are you reading at the moment that you would like to recommend?

On the one hand I’m rereading The Spring of the Ram by Dorothy Dunnett, the second book in the House of Niccolo series, which is an intense, brilliant series set in and among the great trading houses of 1400s Europe. The writing is sometimes so dense that I have to reread a page three or four times to work out what’s going on, but it’s also utterly beautiful, wildly adventurous and sometimes very funny.

On the other hand, for light relief, I’m reading a series of fantasy novellas by Lois Bujold, who is one of my favourite sci-fi/fantasy authors. The novellas follow the adventures of Penric, a young man who is infected by a demon, which he names Desdemona. I highly recommend both series.

How can readers contact you?

There are several options on my website, if you scroll down past the school info. https://liantanner.com.au/contact/

Thanks very much for your responses, Lian, and all the very best with Ella and the Ocean. It is exemplary children’s literature and will hopefully continue to find an even wider and more appreciative audience.

Judge report Patricia Wrightson Prize, 2020 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards:

Ella and the Ocean is a flawlessly composed and executed picture book. It is perfect for young children and will continue to delight on multiple readings. It is also a highly sophisticated, multilayered and allusive text. While in the foreground the story is about a child, and her desire to see the ocean, the book has extraordinary depth – exploring drought, climate change, family, resilience, dreams and hope. The Australian landscape is celebrated and the natural world affirmed.

The writing is simple, yet metaphorical, sensory and evocative with apt repetition of descriptions of the dry as bone land, the revitalising ocean and broken and anticipated dreams. The cyclic narrative arc is consummately crafted. Words and illustrations align effortlessly and the artwork shows an exceptional quality of meaning and depth to conjure family and country – the despair on Dad’s face, Ella’s inquisitive childhood innocence and the juxtaposition of red dirt and blue ocean to create a visceral response.

Ella and the Ocean is a sensitive intergenerational story that reflects the beauty and the terror of our wide brown land and validates the experience of those who live in drought, longing for water. It enables young readers to experience this, and other difficult and fearful circumstances, vicariously. It is a story that could be placed into the hands of children anywhere in Australia and the world over, to be universally appreciated and loved.

https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/awards/patricia-wrightson-prize-childrens-literature

One thought on “5 Writers 5 Minutes”