Borderland by Graham Akhurst

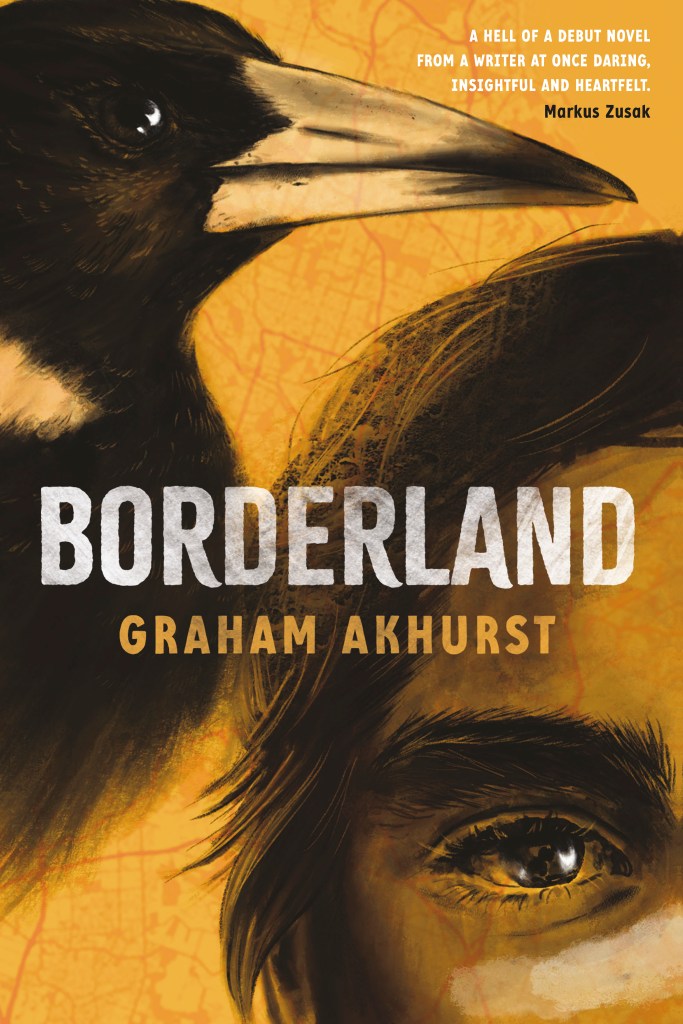

Borderland by Graham Akhurst (UWA Publishing $22.99)

“I thought of songlines and creation story pathways. I wondered what ancient knowledges, Laws, and songs lay across that land. ‘And this is where they will be mining?’ I asked”. (Borderland)

It seems as though everyone is reading Graham Akhurst’s debut Borderland, an atmospheric YA novel with an Indigenous protagonist, Jono, who lands an acting gig that takes him from Brisbane to a remote mining outpost with cultural significance in western Queensland.

Borderland is distinctive and important for many reasons including its characters and their identities (as well as their relationships), its landscape and issues.

It has some truly indelible moments as well as symbolic elements, such as when Jono is lost in his dance, his ambiguous relationship with magpies, his visions and fear, and the stories of Wudun, a protective figure from the Dreaming.

Borderland stays in your head.

Interview with Graham Akhurst about Borderland

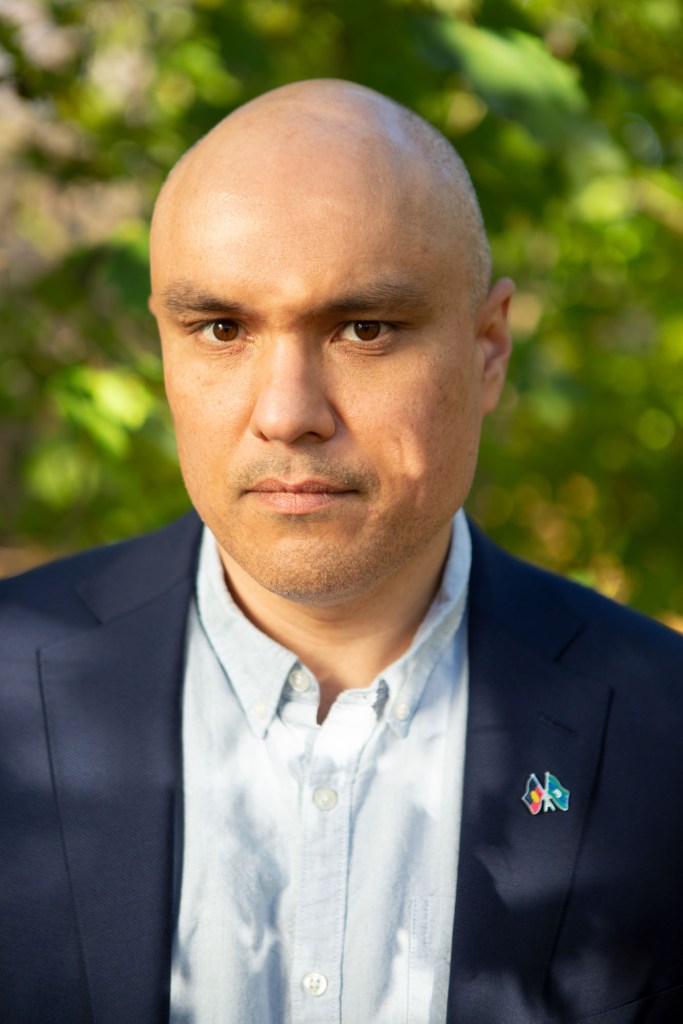

About Graham Akhurst

Graham Akhurst is a Kokomini writer who grew up in Meanjin.

He is a Lecturer of Australian Indigenous Studies and Creative Writing at UTS. Graham began his writing journey in a hospital bed in 2011.

He read and started journaling between treatments for Endemic Burkett Lymphoma. As a Fulbright Scholar, Graham took his love for writing to New York City, where he studied for an MFA in Fiction at Hunter College.

He is a board member for the First Nations Artists and Writers Network and Varuna. He lives with his wife on Gadigal Country in Sydney and enjoys walking Centennial Park with a good audiobook.

(from Graham Akhurst’s website)

******

Thank you for speaking to ‘Joy in Books’ at PaperbarkWords, Graham.

Charmaine Ledden-Lewis designed the book cover for Borderland. She seems to be everywhere at the moment and I’ve interviewed her previously. What do you think it is about her cover artwork that pulls the reader into your story?

Charmaine did an incredible job on the cover of Borderland. I think the way she was able to link the magpie to Jono through the white of the eyes is remarkable. It is also a hint at the Dreaming spirit that chases Jono into his identity and heritage. I feel very lucky to have worked with such an incredible Indigenous artist for the cover of my debut and I wish Charmaine all the continued success she deserves!

What is the significance of your title Borderland?

Indigenous young people cross many borders in their day to day lives and we see this rendered in Jono’s journey. He is a young man who at first is navigating the predominantly white space of a private school in Brisbane and does not fit in culturally or economically. After high school he enrols in an Indigenous performing arts school and also does not quite fit in as he is not as culturally grounded as his peers. So we began to see the micro boundaries that he must navigate as an urban Indigenous young man. However, I also wanted to highlight the macro borders of Identity politics in Australia and also the interface between communities and the extraction industry. These borders often dominate the discourses around Indigenous Australia and I wanted that to be highlighted in the title.

Protagonist Jono and his best friend Jenny attended St Lucia Private school in Brisbane. Is this based loosely on a private school in the St Lucia area? I ask because, apart from the setting, it has similarities such as the scholarship program for Indigenous students, which seems like a positive initiative, but you show a much more nuanced perspective. What is an example of this deeper nuance, experience or knowledge in the novel?

I went to an all-boys private school, St Joseph’s College Nudgee, and St Lucia Private is a fictional representation of my personal experience. Don’t get me wrong, I had a good high school experience, but looking back there were instances of estrangement or feeling outside the experiences of the predominantly white student body. As far as other nuanced experiences and knowledge in the novel, I really tried to load the text with as much symbolism and links to broader issues as possible so that young adults had some weighty topics to discuss around the dinner table and in the classroom. I think our young people today are incredibly intelligent and I wanted to privilege that intelligence in Borderland by making things messy and nuanced just like life.

How does not knowing who his mob is and “where my Country was” increase Jono’s suffering?

A fundamental part of identity development for anyone, but I think particularly for young people, is understanding family history and how it relates to the individual experience. Because of colonisation for many of our young people that journey can be a very difficult one. Often with misleads and missteps but ultimately one of great resilience and eventually connection to place and community. Within this process there can be great suffering in the journey towards understanding one’s place in the world. I wanted to render Jono’s journey so that Indigenous young people can see a little bit of themselves in the text. A spark of truth in the fiction.

The relationship between Jono and his mum is very loving. Why have you created this to be so positive?

Jono’s relationship with his mother is based off my own experiences. My father was a pilot and not around a lot when my brother and I were growing up. He eventually left us when we were adolescents and it was Mum who raised us and grounded my brother and I in culture. I wanted to render the special relationship that so many Indigenous young men have with the matriarchs of their families. My mother is one of the kindest and most generous people I have ever know and I dedicated the book to her in appreciation of all she has done for me and my brother.

I love that Jono’s favourite play and book to read is Leah Purcell’s The Drover’s Wife (I was a judge of the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards the year it won overall Book of the Year). Why have you mentioned this work?

Leah Purcell’s, The Drover’s Wife is an incredible work that artfully threads Indigenous people with Australia’s colonial past. I reference it in Borderland as an intertext because I wanted to honour her art, but I was also inspired by how she connected colonial history with Indigenous identity. It is a marvel of a text and I hoped in some small way to emulate it. I also hope that anyone who reads Borderland might pick up The Drover’s Wife if they haven’t read it before.

You skilfully reveal and hint at a lot of complexity within the context of your story, as well as pain – past and present. What is one small, or big, way that this pain may be alleviated in the future? Following on from the prior question, what is one way that the arts are showing the way?

We have such a rich practice of storytelling in our culture and I think this is a way forward when looking back on a really troubled history. I also tried to make the book funny as there is great healing in comedy and story. Fictional texts are liminal spaces where the reader brings their own personal histories to the page. I wanted young people to feel Jono’s burdens and also revel in his eventual successes. I wanted to hint at and discuss a troubled history in a way that was accessible. As I said before, I think this generation of readers is incredibly bright and I didn’t want to shy away from tough subjects because I think they can handle it and actually respect works of art that can relay a certain truth in a form that often sits so closely adjacent to it. We are in an incredible time for Indigenous literature and I think in genre fiction, particularly, we can contemplate new futures and reach new audiences.

Thank you, Graham, for your reflective and beautifully expressed responses and, not least, for Borderland itself.

I recommend Borderland for readers of Lisa Fuller’s Ghost Bird.

One thought on “Borderland by Graham Akhurst”