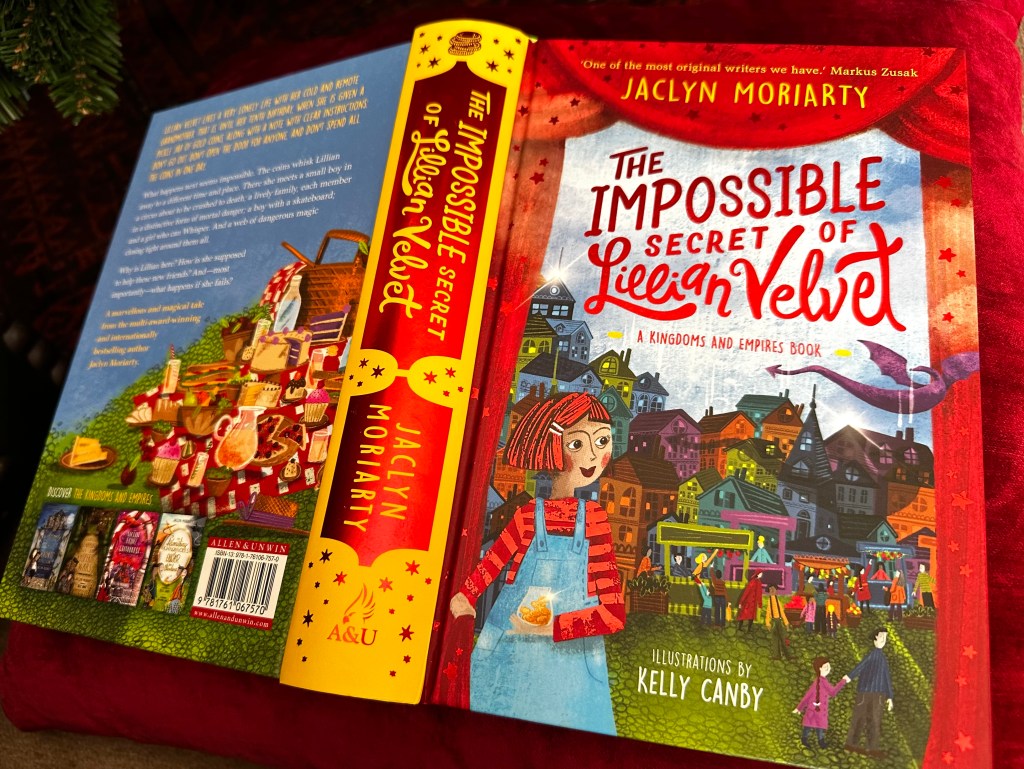

The Impossible Secret of Lillian Velvet

by Jaclyn Moriarty (Allen & Unwin)

“ ‘And what is this world?’ I asked. ‘It’s called the Kingdoms and Empires. It’s like our world, only more old-fashioned. Plus they have magic. The main thing to remember is that Shadow Mages are good and Spellbinders can bind Shadow Magic. Genies are sort of wise, I guess, and exist outside everything.’” (The Impossible Secret of Lillian Velvet)

Family is very important in The Impossible Secret of Lillian Velvet, the fifth novel in Jaclyn Moriarty’s incomparable ‘Kingdoms and Empires’ middle-fiction series. It is intricately plotted, sinuous and warmly satisfying.

The much-loved extended Mettlestone family from the previous books in the series reunite here. These sections are written as fascinating reports.

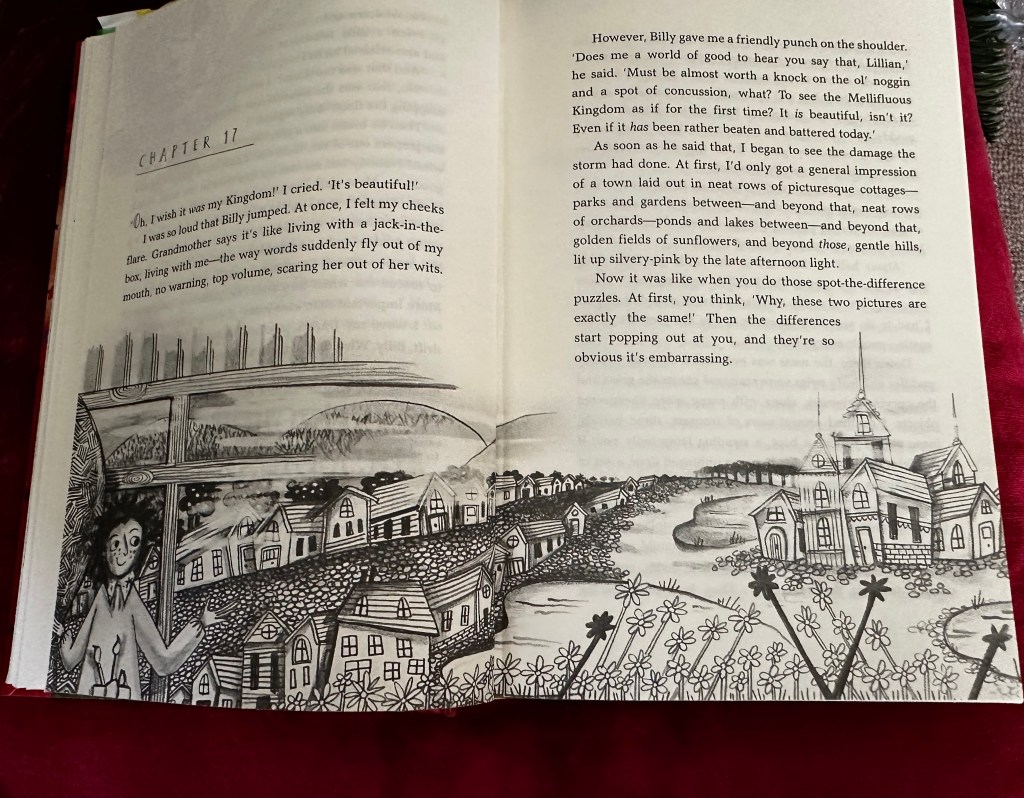

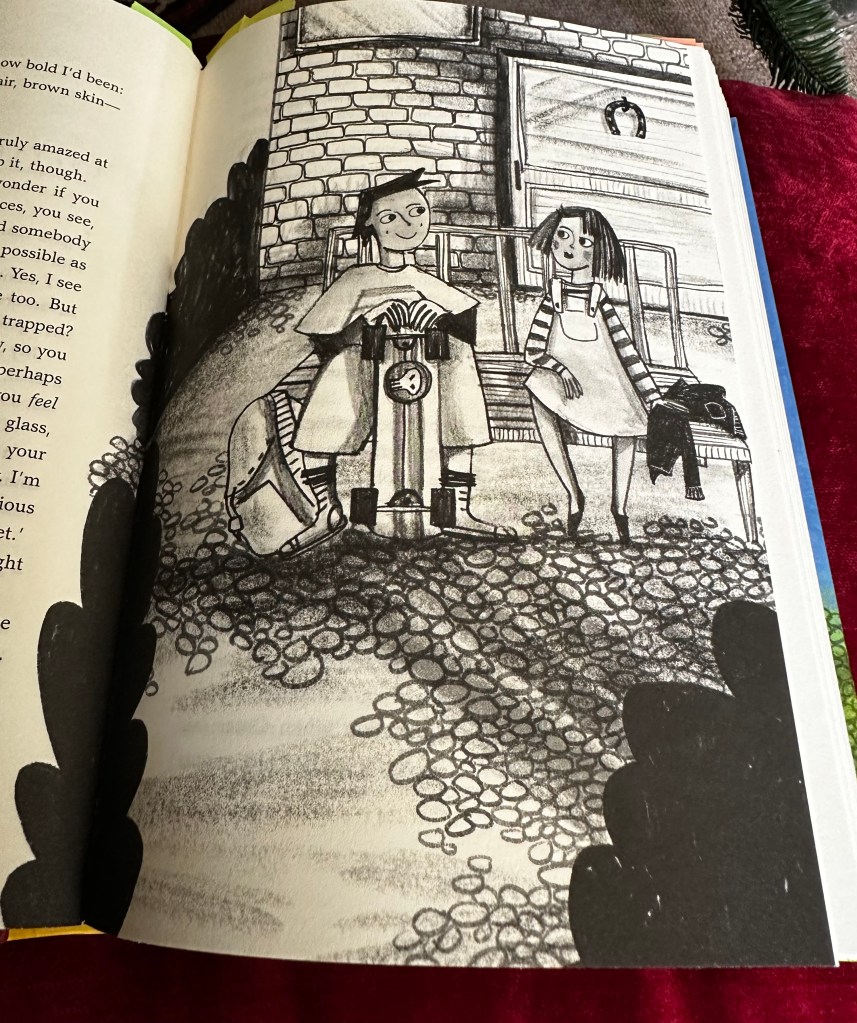

Meanwhile, on her tenth birthday in Bomaderry, Australia, Lillian Velvet receives a pickle jar full of gold coins from her grandmother. This gift seems to make it possible for her to journey into past times and places in the Kingdoms and Empires. She meets Mettlestone family members, beginning with Carrie when they save a colony of Sparks (fountains of light that communicate though music) from Hurtlings (Shadow Mages) in the forest, before encountering artistic Prince Billy in the Mellifluous Kingdom. A circus and more follow before Lillian finally meets Bronte Mettlestone herself.

These episodes are written as chapters.

Genies, Spellbinders, dragons, flying skateboards and, not least, brave, heart-warming Lillian Velvet await the fortunate reader …

******

Thank you for speaking to Joy in Books at PaperbarkWords, Jaclyn.

Thanks for having me! And for that beautiful introduction.

Names are important in your work. Lillian’s full name here is ‘Lillian Velvet’. What is it about velvet that conjures some of the essence of this girl?

I think of velvet as being soft, gentle, elegant and precious while also somehow deep and mysterious.

How is Lillian remarkable?

Lillian has hidden strengths and talents that she does not yet understand. She is remarkable in that she remains hopeful, kind-hearted and optimistic despite her intensely lonely life, and the crushing way she is treated by her grandmother.

In this series you often (but not always) feature one protagonist in each book. Bronte in The Extremely Inconvenient Adventures of Bronte Mettlestone, Esther in The Stolen Prince of Cloudburst, Oscar in The Astonishing Chronicles of Oscar from Elsewhere … Some characters have their names in the title, others don’t.

I imagine that you miss your major character when you move onto the next book even though they may reappear in a later book, perhaps even in a small way, but they’re not the focus anyone.

I love and appreciate Lillian in The Impossible Secret of Lillian Velvet more and more but when Oscar (who featured in the previous book) met Lillian in this new book (even though their meeting was very exciting), it made me miss him.

Do you miss characters when they lose the spotlight? If so, how do you cope and get around this?

This is a great question. I definitely miss characters between books, but I think of it the way you might approach being the parent of a big family: it’s important to spend quality time with each child, making sure they each have a turn of feeling special. Meanwhile, I have to trust that my other children will be okay getting on with their lives.

I knew that Oscar (and Bronte) were going to feature in this book, and I felt impatient to reach their chapters so I could see them again.

(Now I wonder if this is why I have so many dreams in which I have teeny-tiny children (the size of my fingertip) that I’ve forgotten to feed? They turn up in cupboards or top shelves or sitting on my glasses frames. I’m horrified at myself.)

Which character did something that surprised or delighted you? What was it?

It’s only a small thing but I was surprised and pleased when Queen Alys heard the sound of a dripping tap and, rather than call somebody to fix it, went into the bathroom, changed the washer, tightened the faucet and returned to work in her office.

What is one of the new things we discover about the Kingdoms and Empires in Lillian Velvet?

We find out that Bronte’s grandfather (on her father’s side) was a Wheat Sprite and that all land-based Sprites can make a single wish come true in their life time.

We also discover that there’s an original form of Shadow Mages called a Hurtling. It takes the form of sound, shadow and energy, despises life and wishes to destroy it.

Storms are ravishing the Kingdoms and Empires here. Storms also featured in your ‘Colours of Madeleine’ trilogy. How are the storms similar or different between your two imagined worlds?

In the Colours of Madeleine trilogy, the storms were made of ‘Colours’, each colour or shade having a different attribute. So a Lemon Yellow storm was like a sky filled with sharpened darts that could blind you.

In Lillian’s story, the storms appear to be regular, violent storms—along the lines of hurricanes, cyclones or typhoons. Yet, there is something a little odd or askew about them—like the Colour storms, they are otherworldy, manufactured by magic.

What colours do you associate with the book?

Burgundies, crimsons, golds and other rich, dark colours for Lillian; apple green and sunny yellow for the Kingdoms and Empires.

What smell or scent?

Toffee apples, rain on trees.

Also the vanilla coconut of the scented candle that I had on my desk while I was writing it. Lighting candles while I’m writing is a new ritual that I’ve copied from a friend. (Probably just as a new way to procrastinate starting work. ‘Wait, can’t start yet, have to get my cup of tea—nope, not yet, have to get my fruit and chocolate—have to find a scented candle, have to find the matches…’)

Music is associated with several of the Kingdoms and Empires. Could you please give an example from this story?

When Lillian helps Carrie save the Sparks (a kind of tiny True Mage), they thank the girls using music that speaks the language of mathematics; and when she visits Billy, Lillian watches as his Kingdom, the Mellifluous Kingdom, repairs itself through music. Also Billy creates music through his art.

As Lillian begins to recognise that there are connections between worlds, and between the members of loving families, she’s also seeing how different concepts—such as colour, music, scent, art and mathematics—connect and collapse into one another. It’s a little like the possibilities inherent in synaesthesia: people who hear the taste of strawberries like clashing cymbals, or see the number four as orange with the scent of rubber tyres.

Oscar tells Lillian that he spent five days on a rescue mission to save Elves with Imogen, Esther, Astrid and Bronte Mettlestone and their friend Alejandro.

Lillian reacts, ‘You spent five whole days on your adventure with your new friends? … That’s like a book! My adventures are just first chapters of books.’

How does this describe how you’ve written this story?

Each time Lillian is ‘shoved’ into the Kingdoms and Empires, she arrives at a different place and time, and meets a different person. Once she has completed an important task, she is ‘shoved’ back into her own home.

Lillian has read many classic children’s fantasies—and has otherwise led a very isolated life—so she is quick to accept this ‘shoving’ back and forth into an alternate, magical world, especially as it’s accompanied by many conventional tropes of children’s books. But she’s frustrated by the fragmentary, episodic nature of her adventures: the story she seems to have entered is not following the familiar narrative path.

Since Lillian’s grandmother has kept her trapped at home, and treated her coldly and cruelly, there is a part of Lillian that feels worthless and insignificant. She fears she may never play a starring role in life—that she is only a minor character, a sidenote—and that her life will never progress beyond her tantalising glimpses of the great, big world outside.

What she doesn’t know is that each of her small adventures is a piece in a puzzle or mosaic, slowly revealing a picture in which she truly is the hero.

How have you eased or ‘shoved’ this book to fit into the series?

Ha ha, this makes me think of an article I read the other day about how you should organise your home so that everything has a place. ‘If you have to shove an item to get it into a drawer or cupboard,’ the article said, ‘that is not its place.’ (Since reading that, I’ve become increasingly aware of just how much in my home is not in its place.)

Hopefully Lillian’s story belongs in the series. It’s a series that revolves around the Mettlestone family, and each time Lillian is shoved (or let’s say transported), she encounters somebody who is a either a member of the Mettlestone family or connected to it in some way. Her story is linked to minor episodes from the other books,and evolves to reveal how she herself is intertwined with the Mettlestones.

I originally saw Lillian Velvet in a half-dream: I was falling asleep and I saw a girl sitting at a piano in a small, dark empty house. A key slid across the floor towards her. When I woke up I realised that her name was Lillian Velvet and that the key meant she was going to be able to access the Kingdoms and Empires. Over the next few days, I saw more and more connections between Lillian and the Mettlestone family. Eventually, while eating a pickle, I decided that her ‘key’ to the Mettlestone’s world would be a pickle jar filled with gold coins.

Several very subtle issues underpin and permeate The Impossible Secret of Lillian Velvet? Could you please share one of these?

Like many children who grow up in cruel or abusive circumstances, Lillian doesn’t realise that this is not how reality is supposed to be—that she deserves a warm and loving family of her own.

I grew up in a family of six children and my mother also fostered babies and toddlers. They had often been mistreated or neglected, and Mum would focus on loving them and nurturing them so they became happy, fat babies. I was thinking of those little children, and their resilience and hopeful optimism when I wrote Lillian’s character. In particular, I was thinking about how small children accept the reality they’re given, not realising until much later that they might deserve much more.

Locked into our own perspectives, most of us believe that the world we encounter is the only one there is.

Lillian loved reading Dragon Skin by Karen Foxlee, Lirael by Garth Nix and other books. What else would you recommend for young, discerning readers?

I just finished Picasso and the Greatest Show on Earth by Anna Fienberg. The protagonist is heartbroken by a family tragedy, weighed down by a terrible secret, and anxious about a move to a new neighbourhood—yet somehow is also a delightful and funny person for a reader to spend time with. There are also exquisite descriptions of the Australian bush, an intriguing and artistic new best friend at school, and the most vivid puppy I’ve encountered in literature in a long time. I adored this book.

What’s next in your Kingdoms and Empires series?

Bronte’s cousins include a set of three cousins: Imogen, Esther and Astrid. Both Imogen and Esther have played starring roles in books in the series (The Astonishing Chronicles of Oscar from Elsewhere for Imogen, and The Stolen Prince of Cloudburst for Esther), but so far, Astrid has missed out. I keep getting letters from young readers pointing out the injustice of this. And they are quite right. So I’ve just written the first two chapters of Astrid’s story—Astrid has found herself accidentally transported from the Kingdoms and Empires into our world.

[JL This sounds fascinating]

What’s happening with your time travel novel for adults?

It’s called The Tango Dancer’s Guide to Stopping Time (at least, that’s what it’s called at the moment…), it’s about a woman who gets a job at a Time Travel Agency in Neutral Bay, and it will be published in 2025. Thank you for asking!

******

Like the other books in the Kingdoms and Empires series, The Impossible Secret of Lillian Velvet is an attractive hard cover gift book.

I can’t recommend this quality nuanced series highly enough. There is nothing like it and nothing close in an imaginative sense. It can be read over and over again. It is a gift.

Thank you for another outstanding book, Jaclyn.

Lillian Velvet is a legend!

Thanks again, Joy! Really fun and thought-provoking questions

The Impossible Secret of Lillian Velvet at Allen & Unwin

******

SOME OTHER BOOKS BY JACLYN MORIARTY

KINGDOMS AND EMPIRES series

The Extremely Inconvenient Adventures of Bronte Mettlestone My review in the Weekend Australian (& reproduced below as part of a multi-book review)

The Slightly Alarming Tale of the Whispering Wars by Jaclyn Moriarty

My review at Paperbark Words blog

My review in the Weekend Australian (& reproduced below as part of a multi-book review)

The Stolen Prince of Cloudburst My interview with Jaclyn at Paperbark Words blog

The Astonishing Chronicles of Oscar from Elsewhere My interview with Jaclyn Moriarty about Oscar and the Kingdoms & Empires series for Books for Keeps (UK)

******

THE COLOURS OF MADELEINE TRILOGY

The Cracks in the Kingdom by Jaclyn Moriarty

My review in the Weekend Australian (& reproduced below as part of a multi-book review)

My interview with Jaclyn Moriarty at Boomerang Books

My review in the Weekend Australian (& reproduced below as part of a multi-book review)

******

Gravity is the Thing by Jaclyn Moriarty

My review of this novel for adults at Paperbark Words blog

‘The Quibbles’ short story in Laugh Your Head Off Again

Interview about this and Jaclyn Moriarty’s earlier books

******

REVIEWS OF BOOKS BY JACLYN MORIARTY BY JOY LAWN IN THE WEEKEND AUSTRALIAN

These reviews are behind the paywall of the Australian newspaper and most are now unable to be accessed.

I have reproduced multiple-book reviews for those who are interested.

Scroll through to read my reviews of Jaclyn’s books. They are bolded.

******

The Extremely Inconvenient Adventures of Bronte Mettlestone in the Weekend Australian

(scroll through to the end of the multi-book review)

Authors pack a punch

YOUNG ADULT FICTION: BY JOY LAWN

From Weekend Australian Review

January 27, 2018

The following books each contain something unexpected. Take Three Girls (Pan Macmillan, 439pp, $18.99) is written by three of Australia’s best YA authors: Cath Crowley, Simmone Howell and Fiona Wood. They have each integrated a character into this story, which is for more mature readers.

Their characters are brought together by the teacher of the new wellness program set up for Year 10 students at a prestigious private school to help them deal with misogynistic online bullying. Clem, Kate and Ady are randomly put into the same group because they have the longest thumbs.

An elite swimmer, Clem naturally has large hands but she is avoiding training and feels “the future is just like a white blur of skywriting that time has made unreadable”. She’s losing her identity and putting on weight. She is yearning for a physical encounter with older Stu but also feels unsure.

Kate is a talented cellist, passionate but not competitive, who experiments with recording sounds and looping and layering tracks. She’s been “slotted into the box of quiet, studious, geek” who’s good with computers. She works hard to win a scholarship for the sake of her parents’ farm but is pulled between schoolwork and music.

Unlike the other girls, tall, popular Ady isn’t a boarder. She lives at home but her father’s addictions are rattling the family. Ady’s affinity with fabrics, clothes and beauty is rendered in sensory language. She’s unsure why she’s not interested in handsome Rupert and surprises herself by becoming protective of her new friends.

One of the skills of this collaboration is that each character offers insight into the others. Ady, for example, recognises Clem’s confidence to “explore who she might be” and sees Kate as a “quiet musician [who] breaks the rules to walk on the wild side”. The three writers develop and enrich each other’s creations. Take Three Girls deserves a second read to fully appreciate the fine writing and the seeded threads which lead to the denouement.

A Semi-Definitive List of Worst Nightmares (Penguin, 272pp, $19.99) is the second novel by Townsville-raised Krystal Sutherland. Her style here is a mash-up of gothic Wes Anderson with a nod to Markus Zusak’s personification of death in The Book Thief.

Esther Solar dresses as Wednesday Addams, Mary Poppins, Matilda and Eleanor Roosevelt. Due to her demented grandfather’s stories about his career as a policeman who failed to solve the murder of the Bowen sisters, her family believes they are cursed. Her father has lived in the basement for six years, her twin brother Eugene cannot bear darkness and Esther keeps a list of her 50 fears as a superstitious protection from death.

After stealing her list, primary school crush Jonah films her facing her terrors. Their growing friendship gives insight into Jonah’s own troubles and generates much of the novel’s quirky humour, such as Houdini-like locker break-ins and “Lobster Shakespeare”.

Serious issues of anxiety, mental illness and attempted suicide are told sensitively in this thought-provoking novel. It is unusual, intriguing and leads to a discovery of “impossible splendor”.

Emma Grey’s debut novel, Unrequited (Angus&Robertson, 288pp, $19.99), is a funny tale set in Sydney. Its tone and plot echo Shakespeare’s romantic comedies.

Kat is forced to take her younger twin sisters to see boy band Unrequited. She despises the band and spends most of the concert listening to another artist on her iPod, even though lead singer Angus Marsden seems to be looking at her. She also draws the attention of young medical student Joel.

Kat regards herself as a normal, although unsophisticated, Year 12 student who would like to take someone to the formal but is happy watching boxed sets on Saturday nights. She also happens to be beautiful, a talented musician and composer, and is in the chorus of the musical Legally Blonde, where the lead is Joel’s best friend, Sarah.

The farce comes into play when her sisters and best friend impersonate her as “Elle” on Twitter. Angus is desperate to meet her but also wants to explore the music of a young composer he’s heard. Pushy singer Cassidy’s interventions send the story into a kaleidoscopic spin. Who will end up with who? Who will be left unrequited?

Scot Gardner’s Sparrow (Allen & Unwin, 224pp, $19.99) is another fast-paced read. Set on the Kimberley coast, it is an exciting adventure that also highlights the effects of a deprived home life on young males.

Sparrow survives a juvenile prison boot camp accident and swims to a remote, crocodile-infested island. Battling the mud, mangroves and predators, he carves a precarious existence.

This story is interspersed with flashbacks to his childhood as a street kid in Darwin after his mother’s death. Mute and artistic, he is mentored by old Sharkey, who taught him to swim, and is befriended by waitress Elsa, who is later assaulted.

Told from the viewpoint of a victim, Sparrow explores how males from disadvantaged backgrounds can choose different paths. Once he saw the “simple truth before him — kindness pays”, Sparrow learns how to transcend circumstances that could ruin others.

Wilder Country (Text, 272pp, $19.99) is a sequel to Road to Winter, by outdoor education instructor Mark Smith. The novel is set in an Australian dystopia where society has been destroyed by a virus. Finn and his dog Rowdy survive by hunting, fishing and rationing supplies.

Last winter, he helped pregnant Rose escape from the Wilders, roaming gangs of men. Now he feels responsible for Kas, Rose’s sister, and a younger girl. However, Kas is determined to find Rose’s baby, Hope.

This takes them into Wilder country. Even though the Wilder leader laughs at the idea of mercy, Finn faces the moral dilemma of whether he would kill to protect his friends. Kas has had to fight for her life. She is a “Siley”, an asylum-seeker who is treated as a slave. Gender issues also provoke. Wilder Country is a page-turner told in an unaffected, Australian voice.

Landscape with Invisible Hand (Candlewick Press, 160pp, $16.99), by American author MT Anderson, is a markedly different variety of speculative fiction. A short novel written in a lean yet dense style, with an enigmatic title, it satirically traces an invasion of Earth by the alien vuvv (who resemble granite coffee tables).

When the vuvv offer an alliance, world leaders rush to sign away their rights. The vuvv undercut food prices, derail currencies and eliminate jobs. Humans, except for the super-rich who live in high floating communities, become the subculture.

Chloe’s family moves into Adam’s house. The two families make some money but soon detest each other, partly because of Adam’s uncontrollable bowel disease, which could be cured with a simple treatment if only he could afford it.

Adam’s mother thinks “the invisible hand of the market always moves to make things right”. But artistic Adam sees that what was valuable is now worthless and, like the 19th-century artists who painted nature to show industrialists “the beauty of the landscape they were ruining”, his left-handed charcoal drawings seek to show truth. This is a brilliant novella

The Wonderling (Walker Books, 464pp, $24.99), by American author Mira Bartok, is a long, satisfying fantasy novel for younger readers. The Wonderling is a fox-like creature with an innocent heart. He has only one ear and walks upright. He was abandoned at birth at Miss Carbunkle’s Home for Wayward and Misbegotten Creatures and lives there with other human-animal hybrids, known as “groundlings”.

Bird-like Trinket helps him escape. He follows a song only he can hear through the Wild Wood to Lumentown. This sumptuous publication, illustrated throughout by the author, can be read by children themselves or with their families. The film rights have been sold

Sunshine Coast-based Jessica Townsend’s debut, The Trials of Morrigan Crow, first in a series called Nevermoor (Hachette, 451pp, $16.99) has been a top seller. The film rights have also been optioned.

Billed as the next Harry Potter, it is imaginative and full of “wundrous” world-building ideas such as the Hotel Deucalion in Nevermoor, the Skyfaced Clock, the Hunt of Smoke and Shadow, fireblossom trees, the battle for Christmas, and the catchcry “Step boldly”.

Unique forms of travel used by Morrigan to escape her curse include the arachnipod, the Gossamer Line and umbrellas on the Brolly Rail. Once in Nevermoor, she must face four trials. Some important themes underpin this vibrant, magical adventure.

Equally good is Sydneysider Jaclyn Moriarty’s first novel for children, The Extremely Inconvenient Adventures of Bronte Mettlestone (A&U, 512pp, $22.99). Bronte’s parents have been killed by pirates and she must undertake a quest to take gifts to her many aunts. If she fails, her home town will be threatened because the will has been sealed in faery cross-stitch.

The writing is humorous, whimsical and beguiling, with an undertone of sorrow. Elves, Spellbinders, Whisperers, Water Sprites and Dark Mages, as well as lively cousins and the elusive “boy with no shoes”, beckon readers through this intricately and ingeniously plotted tale, which leaves space for children’s own imaginations.

******

The Slightly Alarming Tale of the Whispering Wars in the Weekend Australian

Entering another world

- By JOY LAWN

- APRIL 13, 2019

- WEEKEND AUSTRALIAN

Many novels for young adults are set in a difficult, even violent world, real or speculative. A fraught coming-of-age experience, one that is nonetheless enfolded in hope, is a common theme.

Catch a Falling Star (Walker Books, 256pp, $17.99) by Meg McKinlay, a 2016 Prime Minister’s Literary Award winner for A Single Stone, is one of three middle-fiction novels for younger teens under review today.

Frankie’s father shared his love of astronomy with his daughter before he disappeared in a plane crash in 1973. This coincided with the launch of the Skylab space station, which he had planned to document in a scrapbook with his son Newt (named after Isaac Newton).

The story jumps to 1979, when Skylab is about to return to Earth. In Western Australia, Frankie and her classmates anticipate the descent, planning where they will shelter and fantasising about being astronauts.

Frankie cannot bear to reveal her childhood wish to be an astronomer because of her unresolved grief. Newt is now eight and a precocious scientist. He finds their father’s notes in the broken-down shed that was their Space Shack. He tracks Skylab’s orbit obsessively and merges scientific facts with the Greek Callisto myth that their father is a bear in the stars and will return with Skylab. Frankie also longs to believe in magical stories.

Their mother works long hours as a nurse and leaves Frankie with too much responsibility, particularly looking after Newt. She thinks that Frankie is fine. The author, who is also a poet, subtly explores the alternative meaning of “fine” to depict Frankie’s fine writing and thinking. She also contrasts the broken bone of a young patient looked after by Frankie’s mum with Frankie’s broken family.

Frankie thinks, “I just want my mum for once. I want her here, with us … and not spinning out there in the dark somewhere, in her steady, untouchable orbit.”

Media reports on Skylab’s re-entry change in tone as it becomes a threat. “Tumble” becomes “plummet”. The stars Frankie loved now sicken her but, because her friend’s mother told Newt that their father is a star, he tries to reach him.

Frankie feels that she must catch both him and their father as they fall from the stars.

Frankie’s class is reading Colin Thiele’s Storm Boy and she understands the book “isn’t about a pelican. It’s about losing something important, something that feels like part of your heart. It’s about things falling from the sky while all you can do is watch. About not being able to save the thing you love no matter how fast you run, no matter how much you hope.”

The Slightly Alarming Tale of the Whispering Wars, by award-winning author Jaclyn Moriarty (Allen & Unwin, 528pp, $22.99), is a stand-alone companion to her 2017 book The Extremely Inconvenient Adventures of Bronte Mettlestone.

It is set in the same fantasy world, and Bronte and her friend Alejandro reappear at strategic times to help the protagonists, Findlay of the Orphanage School and Honey Bee from prestigious Brathelthwaite School solve the mystery of the missing children.

Findlay and Honey Bee are good athletes who meet at the Spindrift Tournament. They share the narration, often with different and quarrelsome perspectives on the same event. The structure is sophisticated, with parts told retrospectively.

The writing is whimsical, imaginative and humorous, with taunting acts of rivalry between the schools and magical inclusions such as Radish Gnomes, Faeries and dragons. It is voiced by real-sounding children who address the reader and annoy and care for each other.

In the story, Whisperers are stealing children from the town of Spindrift and across the Kingdoms and Empires, and taking them to the impenetrable Whispering Kingdom. Findlay, Honey Bee and some of their friends allow themselves to be kidnapped so they can rescue the children.

Once there, they are as powerless as the other captives and have to work in the mines plucking strands of thread from rock.

Weighty themes — child slavery, distrust of those who are different, war, expedient alliances, vilification, internment behind barbed wire and unjust treatment of the poor and refugees — are told lightly, yet with impact.

Ultimately, though, this exceptional novel leaves us with a sense of the power and compassion of young people, and their ability to change the world when they recognise their own strengths and draw on the love of their family and friends.

Bren MacDibble is the author of the multi-awarded 2017 novel How to Bee. Her new dystopia, The Dog Runner (Allen & Unwin, 248pp, $16.99), echoes Cormac McCarthy’s The Road — but with the help of dogs.

Most of the world is starving because a red fungus has destroyed the crops. Food is scarce because it is dependent on plants and grass: bread, rice, corn, meat and dairy products. The government has stopped distributing food packages and people are stealing or trading on the black market.

Ella is 10. Her mother, who helped maintain the power grid, has been missing for eight months. Ella’s father goes in search of her and also doesn’t return. Ella and Emery, her 14-year-old part-Aboriginal half-brother, know it’s time to leave the city.

They want to head to a farm owned by Emery’s mother and grandfather. Emery exchanges Ella’s precious tin of Anzac biscuits for a cart, dog harnesses and two huskies to help lead-dog Maroochy and their two other malamutes pull the sled on wheels.

They escape the city on moonlit, “white ribbon” bike paths, then cross paddocks, creeks, gullies and a rocky hillside through red dust. The New Zealand-born author has an affinity with the Australian landscape. She sculpts it as familiar but unromanticised.

They encounter the vulnerable, the kind — and gun-toting predators on electric motorbikes. Ella draws on her quick wits and endurance to keep the tribe safe. She learns that in an upside-down world, survivors must “walk on their heads” and think differently.

The writing in this cautionary but hopeful tale is pared and sparse. It is told in an idiosyncratic style (“my stomach is aching of empty”) that brings the characters and setting to life.

For older readers, Angie Thomas’s two acclaimed YA novels The Hate U Give (released as a movie this year) and On the Come Up (Walker Books, 448pp, $17.99) are authentic, potent representations of a contemporary African-American ghetto experience. They are set in the fictitious gang-controlled, drug-fuelled suburb of Garden Heights, narrated by teen girls and steeped in distinctive, cadenced slang.

The community in On the Come Up is reeling and rioting after a police shooting of a young unarmed man. Security guards at 16-year-old Bri’s school are now targeting the “black and Latinx kids”. Bri is caught bringing contraband — candy — to school and is thrown to the ground and handcuffed.

Bri is like her father: smart-mouthed and hot headed. He was an underground rap legend who was murdered when Bri was four. Her mother, a former junkie, is trying to keep food on the table. Her aunt is a drug-dealer.

Bri feels invisible, powerless and “a hoodlum from a bunch of nothing” until she has the chance to rap in a freestyle battle. This and the other rap scenes are electrifying.

Bri composes on the spot, turning her aggression and angst into a rhythmic flow of sounds and words. Her song goes viral and she becomes neighbourhood royalty. In “the Garden, we make our own heroes”.

On the Come Up is a brilliant, unflinching expose of racism and violence, and a story about how strong-minded individuals and families in tough, disadvantaged societies can survive and save each other. Told in pain, yet with warmth and love, this story is throbbingly real.

Former Australian children’s laureate Jackie French writes across genres and eras. Just a Girl (HarperCollins, 256pp, $16.99) is set mainly in Judea in AD71, when the Roman army destroys a Jewish village.

Grandmother Rabba orders young narrator Judith to carry her to a cave that the women have secretly stocked with food. Judith also rescues her younger sister, Baratha, but witnesses the horrific death of her mother and capture of her older sisters.

Judith has been a shepherd since the menfolk went to war so is skilled at hunting with a slingshot. When threatened by a Roman, she hits him in the forehead with a stone and believes she has killed him. Rabba instructs her to honour the dead by burying him, but she finds him alive, although badly injured.

Caius is a scribe-slave, now freed because the Romans abandoned him. He helps the cave-dwellers survive cold, flood and a wolf attack. His and Judith’s questions about Rabba’s past friendship with a girl she calls Maryiam and her son Joshua prompt Rabba to gradually reveal fragments of the Christmas and Easter stories.

The author draws on her expertise in researching, retelling and linking historical events to outline the tale of Maryiam/Mary, whom she describes as a “dimly seen historical figure”.

French’s writing evokes the village “huddled between lion-coloured hills”, the dank cave and the routine of scavenging and cooking.

Themes of war and its aftermath, slaves, refugees and female worth are both time-specific and universal. Judith learns that, like Maryiam and Rabba, she is never only “just a girl”. She is curious, intelligent and strong. Despite its violent setting and time, this is ultimately a gentle tale of kindness, joy and hope.

Joy Lawn is a reviewer of young adult fiction and children’s books.

******

Colours of Madeleine trilogy

The Cracks in the Kingdom in the Weekend Australian

Aussie authors of young adult fiction attract overseas audience

· YOUNG ADULT FICTION: BY JOY LAWN

- 12:00AM JULY 26, 2014

- WEEKEND AUSTRALIAN

ON a recent visit to New York I trawled through some of the city’s best bookstores looking for Australian young adult fiction. Markus Zusack’s The Book Thief was stocked everywhere and most booksellers knew of Shaun Tan’s ground-breaking illustrated works, with his latest, Rules of Summer, on prominent display. Some stores carried Catherine Jinks’s speculative fiction, as well as Karen Foxlee’s Ophelia and the Marvellous Toy (for younger readers) and The Midnight Dress, without realising the authors were Australian. Other stores had Jaclyn Moriarty’s novels, which are highly regarded in the US.

Sydney-based Moriarty’s latest, The Cracks in the Kingdom (Pan Macmillan, 544pp, $19.99) is Book 2 in the Colours of Madeleine trilogy. Realism is ingeniously wedged into this fantasy. The first book, A Corner of White, won the YA category in the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards and the Queensland Literary Awards, and a Boston-Globe Honour Award in the US.

Madeleine lives in Cambridge, England, the World. She posts letters to Elliot Baranski in the Kingdom of Cello through a parking meter. There are ‘‘invisible and intangible’’ cracks between the worlds, unnoticed except for when pencils, matchboxes or receipts drift through. The authorities in Cello punish anyone who dallies with cracks but Madeleine and Elliot are too focused on their growing friendship to care.

Time is loose in Cello. Seasons wander. There are attacks by dangerous Colours: the Charcoal Grey is a strong wind; the Clay Brown rises like mud, clamping and crushing bones. Some people become addicted to chasing Turquoise Rain, ‘‘which fell like splinters of city lights … mak(ing) the world sing with hidden doors … sparking, folding, fanning’’. Girls stamp in its puddles, the sparks foaming higher than their ankles and shins. Moriarty’s descriptions equal her brilliant world-building.

A narrative arc follows the Royal Family of Cello who have been pulled through cracks into the World, where they have forgotten their identities. Only Princess Ko is left behind to find them. She enlists Elliot into the search after discovering his illicit connection with the World. Between his school, deftball and other commitments, ‘‘Elliot got himself so busy he couldn’t see his way around the knots’’.

Seventeen-year-old Ben Fletcher in British author Tom Easton’s Boys Don’t Knit (Hot Key Books, 288pp, $16.95) also becomes frenetically busy. An incident with the Lollypop Lady sees him on probation doing community service and enrolling in a community course, as well as maintaining his high grades, starting a business, saving his school and dreaming about actor Jennifer Lawrence.

Ben elects to take a course in knitting because he thinks his hot English teacher is running it. Because this novel is a laugh-out-loud comedy, there is a mix-up and she teaches pottery instead, which Ben pretends to take. His knitting teacher is the mother of the girl he likes and he doesn’t want her or anyone else to know what he’s studying.

Ben’s obsessive-compulsive tendencies and mathematical ability make him a knitting natural. He becomes a fan of online knitting sites Stitch & Bitch, Purl and Hurl and Knit Club (knitting’s equivalent of Fight Club). He competes in a knitting competition against a cheat and wonders: ‘‘What would Katniss (Everdeen, The Hunger Games protagonist) do?’’ The climax at the National Knitting Competition becomes a Chaucerian ‘‘extreme sport Combat-knit’’ to rival The Hunger Games. Even though Ben may be unravelling inside, he has learned to deal with his worries ‘‘one stitch at a time’’.

David Metzenthen has also written a book about knitting, The Hand-Knitted Hero, but his most recent novel, Tigerfish (Penguin, 256pp, $17.99), is an award contender for older teens. Set in Metzenthen’s home town of Melbourne, a working-class landscape is suffused with an unexpected beauty of spirit. Sky Point Reserve is a waste ground, the ‘‘last urban frontier’’. A murky danger is signalled by an ominous, menacing tone. The estate is a source of fear but also of freedom. Kindness is present, ‘‘but no one notices’’.

Ryan, with his rough, ‘‘messy rockstar look’’ meets Ariel, who has started working in the surf shop at Sky Point Mall. She has never seen the sea, loves birds and has a natural, indie style. Ryan is drawn to her and is able to help with some of her family troubles. He is cool and tough, ‘‘slippery, slack’’ yet good-hearted — one of Metzenthen’s signature multidimensional male characters.

Like Ariel’s birds, the tigerfish is a potent symbol. In attack it resembles the bull shark but could it be both hunter and hunted — like some of the volatile characters who inhabit Sky Point?

Another fish is used as a symbol in The Minnow (Text Publishing, 256pp, $19.99), by New Zealand-born NSW resident Diana Sweeney. A minnow is the antithesis of a tigerfish; undersized and non-threatening. Fourteen-year old Tom (nickname for tomboy) has fallen pregnant to her father’s friend Bill in blurred circumstances. They have fished, swum and gravitated around each other since Tom’s parents and sister died in the Mother’s Day flood a year ago.

Tom talks to her unborn Minnow and, in a surreal touch, Minnow speaks back. Tom also spars with her spirited deceased grandfather. Older people are treated with affection and respect by their grandchildren. Family is paramount and genuine friendship, particularly with Tom’s gay friend, Jonah Whiting, suggests an optimistic future despite the difficulties of being a schoolgirl mother.

Words are important to both Tom and the author. Tom constantly refers to her thesaurus and dictionary, and some characters’ names embellish the fish theme. The writing in this debut novel has a thoughtful authenticity and the loose ends are resolved with restraint. It is a memorable and beguiling cautionary tale for mature teens and older.

Ella West is a NZ writer who has written a place-specific novel set in a radiata pine forest and sheep farm near Canterbury. Night Vision (Allen & Unwin, 192pp, $14.99) is a suspenseful thriller. It is written in a simple style and is original and unexpected.

Fourteen-year old Viola is named after the instrument her mother plays in the NZ Symphony Orchestra. Viola also plays Bach, Brahms and Vaughan Williams on this instrument. She has no idea how talented she is because her mother-teacher has never praised her playing and she doesn’t meet other people in person because of a life-threatening medical condition, xeroderma pigmentosum. The sun burns her skin with only limited exposure, causing cancers which metastasise. XP children are called ‘‘moon children’’ because they generally only go outside during the night.

The forest is Viola’s night playground. While her parents sleep in their isolated farmhouse, she ventures outside wearing her night-goggles. She knows the trees and the animals, especially the morepoke, NZ’s native owl. One night she witnesses a shocking event and the foreboding of death, signalled from the beginning, intensifies. As with all the novels reviewed here there is, however, an ultimate sense of hope.

These and other quality titles from Australasia are reciprocally appreciated by YA enthusiasts in the US and Britain. Our YA literature deserves its growing profile and should claim more and more space in bookshops here and around the world.

******

A Tangle of Gold in the Weekend Australian

(scroll down to read)

Young adult fiction: Millard, Moriarty, Graudin, Savit, Goodman

- By JOY LAWN

- 12:00AM APRIL 2, 2016

The Weekend Australian Review

War is the narrative that subverts and sabotages too many lives, particularly the lives of the young. It threatens and shatters the characters in these new young adult novels in different ways.

Manny in Glenda Millard’s sublime The Stars at Oktober Bend (Allen & Unwin, 288pp, $19.99) is a scarred child soldier who escaped from the war in Sierra Leone after the nightingales stopped singing. A warm-hearted Australian couple now cares for him, but he craves forgiveness and runs to hide from his memories and secrets.

He finds another beautiful, damaged young person, Alice Nightingale, on the roof of her house at Oktober Bend, “like a carving on an old-fashioned ship, sailing through the stars”. She is throwing fragments of a poem into the night. Manny also discovers one of Alice’s poems written on an empty flower-seed packet, folded like a fan and pinned to a poster.

Alice has been leaving poems in public areas as gifts of words and music in place of her stumbling speech, and they become a paper trail for Manny. Alice and Manny (short for Emmanuel) tell their stories in their distinct voices. Each is unique. The meaning of their names is potent. Alice has a sensuous inner light and soul that Manny is drawn to, but her body and brain have been hurt by a trauma whose cause is unclear for much of the story. On a starry night when she was 12, Alice was viciously attacked.

Millard tiers Leonard Cohen’s Anthem with her own lyrical images of birds, feathers and flight, as well as light through cracks. Her sensory prose is filled with sound and colour and creates a sense of hope for the broken. Manny looks between the cracks to recognise Alice: the girl who makes exquisite fly-lures and writes jewelled words in her Book of Flying and who fell into that place between heaven and earth where “the sun is swallowed up between the violet lips of dusk”.

In her minimally punctuated, lower-case verse, Alice at times “spewed” words in “crimson, marigold and rose” and ponders why evil is embodied as black and not blood red; and whether it is the purpose of the stars to brighten the colour of midnight.

Another exceptional Australian writer who melds cracks, colour, light and dark into her writing is Sydney-based Jaclyn Moriarty. A Tangle of Gold (Pan Macmillan, 528pp, $19.99) is the final volume in The Colours of Madeleine trilogy, following A Corner of White and The Cracks in the Kingdom. This is one of our great and most original fantasies, ricocheting between the real “World” of Cambridge, England, where protagonist Madeleine lives, and the invented world of the Kingdom of Cello, where the other major characters are located. Elliott lives in “Bonfire, the Farms” and Keira in the province of “Jagged Edge”. The complex story is told from each character’s viewpoint.

“Living Colours”, the bewildering monsters from the Kingdom of Cello, are buffeting the provinces with intensifying Colour storms: vicious Greys and Purples, Spitting Fuchsias, Jangling Violets and a second-level Maroon that melted the train line. While Cello’s Colours are rampaging, the real World is seeping sorrow because sadness can’t escape now that the cracks between it and Cello are being sealed.

Madeleine receives letters from Elliott, and now Keira, through a crack in a parking meter. Like Moriarty’s more realist novels, there is an elated sensitivity and glee as the imagined world of Cello intersects with the real World.

War is building in Cello. The aggressive Hostiles are trying to wrest the ailing Kingdom from the Royals. Madeleine, Elliott and others must prevent all of the cracks from being closed so that the healing Cello Wind can return.

The light in Cello is tangled and Madeleine must also untangle the darkness and the liminal spaces between worlds and peoples. Madeleine’s movement between worlds becomes a “sensation like reality tearing itself along a perforated line”. Readers have the pleasure of unravelling not only plot strands but also Moriarty’s plot-bending and play with pacing. Her writing is also joyous and humorous.

Historical figures such as the poet Byron, who epitomised dark and light, along with Shelley, Newton, Leonardo da Vinci and Vivaldi wind their way through the story. They are equalled by Moriarty’s own inimitable characters, such as Samuel from Olde Quainte and kind, big-eared Gabe from Bonfire, who shelters Keira and is simply desperate to ride her bike.

Like Keira, Adele Wolfe in Wolf by Wolf (Hachette, 320pp, $19.99), by American author Ryan Graudin, is a motorbike-racing champion. Wolf by Wolf is an enthralling, adrenalin-fuelled story in the vein of Matthew Reilly’s scintillating Hover Car Racer or Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games, but with more thoughtfulness and depth, particularly in its contemplation of issues of identity, racism and the good and evil in humanity, past and present.

Once upon a time, there was a girl who lived in a kingdom of death. Wolves howled up her arm. A whole pack of them — made of tattoo ink and pain, memory and loss. It was the only thing about her that stayed the same.

The girl is Yael, who was selected by a Nazi doctor, the Angel of Death, in 1944 for experiments in melanin manipulation. Unknown to the doctor, as she grows she is able to manipulate her appearance, “skinshifting” to modify her colouring, height and voice. The black wolves are tattoos representing five names, stories and souls that hide her concentration camp numbers. The story is set both in Yael’s childhood and in 1956, in a world mostly occupied by the Third Reich after Germany won World War II. The tenth Axis Tour, an extreme annual motorcycle race across three continents with 10 German and 10 Japanese riders, is imminent.

Adele Wolfe won the ninth Axis Tour. Now 17, Yael works for the resistance and skinshifts to pose as Adele. Despite protective interference by Adele’s brother Felix and ruthless ambushes by Japanese rivals and handsome Hitler Youth member Luca, Yael is determined to win the race and kill Hitler.

Anna and the Swallow Man (Random House, 232pp, $19.99) is set during World War II, when the Germans control much of Poland. It is an extraordinary allegorical and metaphorical debut by New York actor Gavriel Savit, dense but riveting.

After seven-year-old Anna’s professor father disappears, she encounters the unfathomable Swallow Man. He can summon swallows but also knows of an endangered bird species of which only one is left. Anna and the Swallow Man follow ‘‘Patterns of Migration’’, crossing borders and rivers on a seemingly nebulous route around Poland and into Soviet-held territory, evading Soviet Bears and German Wolves. They may be chasing the last “rare and beautiful bird around a battlefield upon which an endless pack of Wolves and a Great Bear … were pitched in endless war”.

The Swallow Man shares Anna’s proficiency in many languages. He teaches her guiding principles such as how to avoid dangerous people, and “Road”, the language of survival where Anna is the “river” and he is the “riverbank”. The Swallow Man can also speak the language of the birds and uses this to pray for his antithesis Reb Hirschl, the bright, seemingly foolish Jewish man they meet — a man others draw borders and boundaries around.

In this tale, names are dangerous and must be kept secret; the legend of the Alder King twists through the narrative, and stories are carried as protection.

High society of the 1800s is a different battleground and war is fought with unusual weapons in Lady Helen and the Dark Days Club by Melbourne-based New York Times bestselling author Alison Goodman (HarperCollins, 448pp, $19.99). The Dark Days Club is the first in a trilogy that blends Regency mystery-romance with wit and the paranormal, effectively creating a new genre.

Lady Helen is tall and thin, with an inner fire and some unexpected gifts, which are accelerating now that she is 18 and expected to be married after her first season. She is able to decipher people’s true feelings, has increasing strength and reflexes, and sees shimmers around certain people. Her mother disappeared under the stigma of being a traitor.

Goodman has incorporated fascinating research, such as the Luddite riots and politics of the time, the Ratcliffe Highway murders and the Bow Street Runners. Like Moriarty, she interweaves historical characters such as Byron into her story, here as a friend of Lord Carlston, who is rumoured to have killed his wife. Helen must decide whether to trust this striking, impenetrable man and join the Dark Days Club to fight the supernatural evil of a Grand Deceiver. Light against dark; war is afoot.