The Crying Room by Gretchen Shirm

Author Interview at PaperbarkWords

Gretchen Shirm is a writer’s writer. Her new novel The Crying Room is a masterclass in writing. It’s an immersive story about women (mainly) and their relationships but it’s inimitable quality, in my opinion, is the writing, which adeptly moves from introspection to pathos, pain and even hilarity. It is elegiac.

Readers will enjoy the tale and the writing. Writers will absorb much about the craft and skill of writing.

The Crying Room is published by Transit Lounge.

******

Thank you for speaking to ‘Joy in Books’ at PaperbarkWords, Gretchen.

Where are you based and how are you part of the literary community?

I live in inner Sydney with my husband and daughter, but right now I am sitting in the library of the B.R. Whiting Studio in Rome, thanks to the Australia Council for the Arts. The studio is near a hospital and I can hear the peculiar wail of the Italian sirens on the street outside and the irregular tolling of church bells remind me I am not at home.

In terms of writing community, I have picked up writer friends who I both adore as individuals and admire as writers over the years — sometimes at residencies, sometimes meeting at events, festivals or launches. These people are very important to me, because they understand the unique struggle of writing. I don’t necessarily see them very often, but whenever I see them we immediately talk about important things!

One of the writers who has been dear to me as a friend and incredibly important as a mentor has been Tegan Bennett-Daylight, who reads my drafts and is herself an incredible writer and teacher. Honestly, the number of excellent books Tegan has nurtured into the world, including her own — the woman deserves an actual medal.

I also have a book club that meets semi-regularly, although lately it has been more like once a year, of writers and critics whose reading recommendations are actually superb. I really do believe that writing is about having an extended conversation with books, so reading broadly and well is incredibly important to me, not to mention inspiring. I also find it enriching to hear other people’s perspectives on books, because I do think everyone responds differently.

I have greatly admired your literary criticism over the years. Where do your reviews appear? Which one, or more, reviews do you see as a highlight or epitome of your criticism? Why?

Thank you! My reviews mostly appear in the Weekend Australian these days, or occasionally in the Age. I have less time lately to chase this work. But I do love it, because I really enjoy working out why a book works, or what it’s trying to do. Although there have been some exceptions, I do feel that virtually every book I’ve read has enriched my life and writing in some way.

I actually found that when my daughter was very young, I was doing a lot of reviews, because that was all I had mental space for and I really did want to keep a connection to books. I also think that this period of intense criticism and reviews led to The Crying Room, in the sense that I just absorbed so many different styles and forms of expression over those years when I was reviewing so many books.

In terms of my approach to reviewing, I suppose it appeals to me so much because it’s only when I sit down and write the review that I actually understand the effect the book has had on me. Sometimes I have an immediate strong response to a book, but when I sit down to write about it, I really have to tease out what that response is about. One example would be my review of Sheila Heti’s Motherhood (https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/motherhood-by-sheila-heti-gives-birth-to-maternal-dilemmas/news-story/757c0dd97574c3593c73dde3f50c207b) . My initial response to that book was that it was not quite as strong as How Should a Person Be?, but as I began to write about it, I understood how deeply layered and complex it was in the way it drew out the multiplicities of self and how motherhood relates to that. Many, many years later I am still reflecting on that book, which I do think is a mark of a masterpiece.

I also remember my review of Rachel Cusk’s Kudos being quite illuminating for me, because the Transit trilogy had had such a big effect on me, and when I sat down to write that review I really was trying to nut out what it is about those books that were innovative. I think it was important to me, because Cusk (who I unequivocally adore as a writer), is such a divisive figure amongst writers. Many writers I speak to admire her writing, but don’t feel moved by it — which is not my response at all. I think one of the things that I realised after writing this review is how important form is to Cusk, and the precision with which those books are crafted places attention on the language itself as a means of expressing oneself (https://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/rachel-cusks-kudo-the-third-in-a-trilogy-of-stacked-dolls/news-story/59cd7ed8f733c9825aef0a2bb5476ca9).

Your top 5 books for the year appeared in the Weekend Australian’s Best Books of 2023:

Stoneyard Devotional by Charlotte Wood

Soldier Sailor by Claire Kilroy

Chain Gang All Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

First Love and My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

I also appreciated Stoneyard Devotional and am keen to follow up some of the others, particularly Chain Gang All Stars. Are there any thematic, stylistic or other links between these books?

That’s a very interesting question. I don’t think that there are necessarily thematic links, but I do think all of these books relate to my own writing in some way. I particularly admire Wood’s writing in that it’s so understated, and extremely resonant and meaningful even though it’s not ‘about’ something big. I get so fed up with the idea that books need to be about a war, or an historical event, or have some broader context other than themselves. In my experience the most impactful books I’ve read don’t fit into that category (Cusk, Heti, Wood are excellent examples of this). Also, the obsession with the need for novels to be about something larger than themselves sidelines narratives about women’s lives, the importance of the family and home life and that horrible word ‘domesticity’. Home-life, parenting, families: these are profoundly influential and impactful experiences that define us for the rest of our lives. I get a bit fed up with books that ignore that.

Charlotte Wood has also written beautifully in the Luminous Solution about the idea that publishing houses are more and more obsessed with how a book can be sold, rather than whether the book is valuable on its own terms, which I think operates to the detriment of these quieter but nonetheless important narratives. And more particularly, the stories that women write. That’s part of the reason I poke a little bit of fun at Cormac McCarthy in The Crying Room — McCarthy looked at humanity and he saw the consistent theme of it was violence. I think if you’re a woman, the more reliable theme that pervades every life is the task of nurturing others.

Claire Kilroy’s spectacular novel Soldier Sailor is an example of this — it’s exclusively about a mother and her experience of raising a newborn child. She examines that unspeakable truth that many women confront, at how utterly singular the responsibility of caring for a baby is, and how men are often sidelined in this process. But the narrator also examines the way she is implicated in disempowering the husband and enabling his feelings of helplessness. So many novels that tackle this subject matter gloss over the profound complications of caring for another person, but Kilroy actually meets them head on. I mean, this sort of a novel effects all of us, because we all began life as entirely dependent on another. A lot of writers have tackled this subject, but play down some of the more difficult details. In my opinion though, this is what literature is for: to give voice to the experiences in life that would otherwise remain unsaid.

Of course, Chain Gang All Stars entirely cuts against this trend, because it does have a context, which is the cruelties of the American justice system. But I felt so inspired after having read this book, because Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah imaginings in this book were so wild (and violent), but they were also clearly tethered to the self-perpetuating nature of crime and punishment in America. He used footnotes to allow this reality to creep into his speculations so deftly and that is something I’ve been working on lately, how to allow facts to bleed into fiction. For me, the form matched the content so beautifully. And whilst it does have this larger context, the book feels incredibly personal to him as well — even the violence in that book is intimate.

And Gwendoline Riley, I mean again she’s one of these writers who is finally getting the attention she deserves. Her books are about domestic relationships, and about love, but I just feel that she’s saying some wonderful (and often unspoken and maybe unspeakable things) about love which is that it is incredibly complicated. And people who love each other do manipulate one another, they are flawed, and they can actually be cruel, or at the very least unwittingly insensitive. Yet there is love! Emotions are messy and in my experience books that ignore this experience of life reduce its wonder. And Riley’s prose, is just utterly forensic — I mean her conversations on the page are so precise, you can almost hear them being spoken. I always teach Riley when I’m covering dialogue.

Now that I think about what connects these books, I suppose it might be something like they feel incredibly personal. There is the sense that the writer is risking something.

What other book/s would you like to add to your list?

A book I read in the dying days of 2023 was Susie Boyt’s Loved and Missed, which was exquisite. Again about mothers and daughters, and also proxy-mothers. The prose is sublime. It deals with a mother who essentially takes her daughter’s daughter into her care, because of the mother’s addiction problems. Again, such a thoughtful treatment of complicated relationships. This sentence blew my mind: ‘Sometimes I think there was something about loving my own child that provoked fury in the part of me that had gone unloved itself.’

I would also add Heidi Julavits, The Folded Clock to this — although it’s a few years old now, and it’s essentially a diary in which Julavits examines the unfolding of her life and also what they reveal about herself. It’s incredibly clever and also funny. Through form, and a reflexive treatment of self, she makes so much out of everyday life.

What tip/s would you give aspiring, emerging or established book reviewers?

I mean, I suppose my suggestion would be to approach the book from a position of curiosity, rather than judgment. I can’t stand reviews that attempt to make some sort of authoritative pronouncement about the value of a book. It’s my job as a reviewer, not to dictate how the book ought to be received, but help a potential reader to work out what their response to it might be (which might very easily be different to my own). I’m more interested in reviews that tell me what it is, how it is what it is, what is it trying to say. There simply isn’t, or shouldn’t be, fixed positions when it comes to books. Different interpretations are what makes book wondrous.

I used to write music reviews in my early-twenties for a now defunct street-press magazine named Revolver, and that early version of me was extremely judgmental and I think closed-down sometimes to what the musician was trying to do. I think those reviews said a lot more about me than about the music. Now, I’m much more open in my approach to criticism. And to life, really.

What skills do you use for both reviewing and fiction writing?

I feel like I hold these parallel rivers in my mind — the critical stream and the creative stream. I don’t find that there’s much of a cross-over, except to the extent that inevitably I use the insights I gain from writing reviews and analysing books into my own fiction writing. I think this probably comes from a decade of legal practice, when fiction writing was very much a sideline activity.

Which 3 words do you love (or tend) to use in your writing?

Oh god, that is a difficult question. I feel like I always use ‘suddenly’ and ‘just’ way too much! Although happily editors tend to pick up on this before publication. I think the difficulty is that I’m probably not aware of the words I tend to overuse, because I don’t do so consciously. I quite like ‘yet’, because it allows complications to be introduced.

I almost certainly overuse the phrase ‘as though’, which I’m often picked up for by editors, but like only applies where the comparison is to an object, otherwise it is grammatically incorrect! Grammar matters and I also think that an expression like this tends to go relatively unnoticed.

I remember when Gail Jones read Where the Light Falls for me and pointed out that every car I had described in the manuscript was silver! I know this sounds crazy for a writer, but it wasn’t until she’d pointed out some of these linguistic tics of mine that it became clear to me how important words are to writing.

******

The Crying Room

Your new novel The Crying Room has been highly commended by other acclaimed authors. Which endorsement particularly means a lot to you?

Helen Garner’s endorsement meant a great deal to me, because Postcards from Surfers is my favourite short story collection of all time! But Gail and Tegan have also mentored me in different ways, so it was also incredibly important to have them behind me, so to speak. Gail Jones was my doctoral supervisor and she really opened me up to new ways of thinking about the world.

How is the crying room symbolic in your novel?

Well, I suppose The Crying Room is dealing with the crucible of family life, and how our families shape the way that we respond to the world for the rest of our lives. How emotions exist and are valued inside families is incredibly important to that. Our emotions and the expression of them are keys to who we are as individuals, and I think how space is made for those inside families influences us profoundly.

Could you please briefly introduce your major characters and their relationships with each other?

The three main characters are Bernie, her daughters Susie and Allison and Allison’s daughter Monica. Bernie is a difficult woman, who comes from a background of poverty and deprivation and her impact on Susie and Allison is understandably life-long. Susie becomes a proxy-mother to Monica, who acts out against Allison’s parenting method.

It’s about three generations of women and how their identities are intimately connected. Formed in response to and reaction against each other. It’s about that delicate sense of becoming an individual and belonging to a family at the same time — the two things aren’t necessarily easy to balance.

What are some of the catalysts that disturb or disrupt their lives?

They are influenced both from inside the relationships and outside of them. So their relationships with each other are often fractious, but on the other hand they are the mainstay of each others lives. Monica is the writer of the family, and her project is understanding these women and figuring out why they are the way they are. In an act of, what seems to Monica to be an abandonment, Allison is sent to live with her aunt Susie, but we learn that things are much more complicated than that.

Susie struggles with interpersonal relationships for most of her life, but finally she settles into a relationship and changes her career. The disappearance of her partner in an airplane though threatens to unbalance all of that.

I think Monica’s decision to write about this family is probably the key disturbance in The Crying Room, because it’s this decision to turn back, to reflect on these lives and to understand their impact on her that makes change possible for these women.

I enjoyed your references to other artistic forms. Bernie thinks that she and her daughters resemble Matisse’s dancing women. Susie dreams of Chagall. Why Chagall?

Yes, my husband bought the reconditioned DVDs of The Shock of the New and I remember being very moved by the fact that Matisse continued to make these cut-outs after a debilitating illness, because that was all he could do. They are incredibly simple, but also quite archetypal which is why I chose them.

When I was in Japan on a writing residency, I saw a Chagall exhibition in Nagasaki. I was really impressed with his use of colour in his painting. The colour was both intense, but abstract almost like a dream. I think the word I use in The Crying Room is ‘quilted’ and that’s what impressed me, the fact that the colours seemed so layered. Also the bride paintings are so playful and optimistic.

Why does Monica read Virginia Woolf and Christina Stead? Why these authors?

I suppose both because they are both at their heart writing about the complexity of families. Virginia Woolf said that she didn’t exorcise the influence of her parents from her life until she wrote her fifth novel To the Lighthouse, when she was in her forties. I might also have added Elizabeth Harrower, but she isn’t so much of a cultural figure (although she should be).

I was very interested in Monica’s writing and writing classes. Early on Monica’s writing demonstrates ‘elegant descriptions’ but is ‘airless’. Her teacher advises her to ‘Embrace awkwardness’… ‘Let your characters do weird things’ …, ‘get angry … act out or break something’.

Is airlessness and reliance on elegant or other descriptions a common flaw you find as a teacher of creative writing? How is it something you address in your own writing?

This is more or less about my own writing. I think for a long time, I didn’t really understand how to introduce emotion into my fiction, although I also see this fairly commonly in my students. I think students are told ‘show don’t tell’ in a way that is unhelpful, and they think it means ‘don’t show any emotions’. But language and emotion are intimately link. Fiction is ultimately, or should be, a conduit for emotion.

I think for a long time there are things in my fiction that I have been not saying, or that I have been silent about. Or perhaps even that I haven’t understood about myself. Anne Enright says that fiction is ‘words on a page’ and I do think that once you realise this, it is incredibly freeing. Fiction isn’t life — The Crying Room is certainly not at all reflective of my family life, but fiction is a place to put emotion. Feelings are not permanent, they change and evolve, but it’s very important to pay attention to them. Ultimately, I think my fiction is the place where I put difficult emotions, things I need to pin down and explore. There is no truth to my fictions apart from feelings I’ve had.

Margo Lanagan has an interesting passage about this in her interview with Charlotte Wood in The Writer’s Room, where she says that when writers are starting out they overdo descriptive detail because they lack confidence, they think that their readers won’t believe them unless they embellish it with prose. Sometimes descriptive detail is very important, but a writer needs to learn where to deploy it. Using details are a way of signaling to the reader what is important in what they are reading. A writer really has to learn when to use descriptive writing, and when to allow the subject to simply speak for itself. I think details help the writer scaffold the reader’s emotional response.

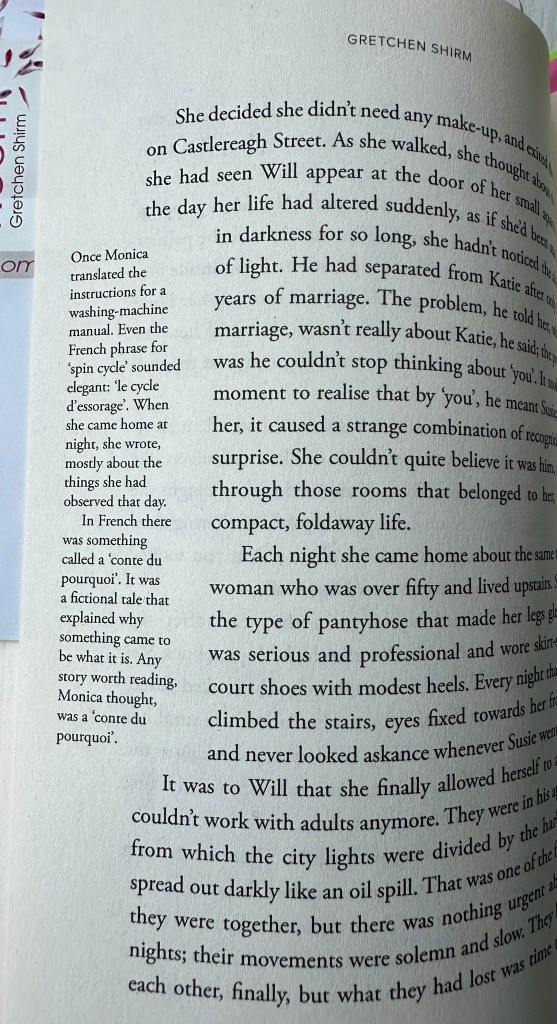

You do something fascinating and structurally ground-breaking – beginning when Susie is in Japan – with sidebars about Monica’s writing assignment, translating and book. What is happening here?

The idea for the margin notes came from a book called The Trick is to Keep Breathing by Janice Galloway. I read that book back in my twenties and the margin notes she’d used had always stayed in my mind. They were a bit different to The Crying Room, in that they were fragments and were kind of incidental to the narrative itself. When I was writing the Crying Room, I thought ‘Hmm I wonder if I could…’ And then I wondered if I dared to because it seemed so unusual, but that’s how it started. Ultimately, I think Monica is the character who brings the book together, and I guess from a technical point of view, having the marginalia allowed me to introduce her book and disperse it throughout the book.

Although when it came time for publishing, the only way to include the notes was to make them bite into the page. I created a massive headache for the typesetter by the way!

You do something else revolutionary with Chapter 9: ‘Witness’, which is crossed out and introduced by Monica’s note to the editor. Without spoilers, what can you tell us about this chapter?

Not revolutionary because I shamelessly stole the idea for the strikethrough chapter from Zoe Heller’s Notes on a Scandal. Although my memory of Heller’s book was that a whole chapter was written in strikethrough font, but when I went back and looked at it, it turned out it was only one paragraph. Obviously, it had a disproportionate effect on me! I feel as though some books I read are just permanently in me.

I suppose part of this was about the tension between speaking/not speaking, or not wanting to hurt her family, which is at the heart of Monica as a character. I see this all the time in students writing, they are afraid to say certain things because of the impact they might have on others. As Elizabeth Strout says in My Name is Lucy Barton – that is not the way writing works.

Fiction has to feel real and intimate, even though it isn’t and the struggle I see in the writers I teach is that they lack the confidence to say what they want to say. They haven’t given themselves permission, but writing well is about honoring the writer’s perceptions. A writer’s own view of the world, their own experience, is unique to them — yes it may be different to other people’s perceptions but that is what makes it valuable. I suppose I was trying to animate this tension in Witness.

I think the impression of an individual, of another person’s consciousness that one gets from reading is often the thing that makes fiction so vital. ‘Only connect’, said E.M. Forster in Howard’s End.

So I hope, this form matches something I am trying to say about Monica and about writing.

Monica’s teacher said,

“‘Every writer has a subject and, if they’re lucky, they find a way to address that subject differently over the course of their writing life.’ This, she realised, was her subject: these women in her life and the effect they’d had on her. She would always, she knew then, in one way or another, be writing about that.”

How is this relevant (or not) in your own writing?

I definitely think this is true for some writers, Elizabeth Strout, Anne Enright are two examples for who this is true and writers who’ve both influenced me strongly. I think to some extent it is true for all writers in the sense that all you have is yourself, your individuality, your own experience of the world and in fiction you are finding new ways to deploy this to make something new out of it. And that’s the key — you’re taking what’s familiar to you and turning it into something new. Anyone who thinks this is solipsistic should reflect on the fact that Rembrandt painted over fifty self-portraits.

I’m not sure how true or not it is for me. I definitely return to motherhood, and being a child and that experience over and over again, which is something I’ve experienced both as a child, and as a mother. I also had the privilege of being an egg-donor to my brother’s children and watching them grow and be parented by someone who wasn’t me. Certainly all of these experiences showed up in The Crying Room.

Most of my books would be described as being about family, or about the home. But then, the novel I’ve just submitted for editing Out of the Woods is based on an experience I had working as a legal intern in the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia, and so it perhaps represents a departure for me in that respect. On the other hand, it’s also a very intimate treatment of that experience so maybe it is not a huge departure after all.

In preparation for this interview, I am so glad that I reread The Crying Room and discovered even more of its artistry and treasure.

Thank you for your incredibly generous and thoughtful responses, which are another master class in themselves, Gretchen and all the best for this important book.

One thought on “The Crying Room by Gretchen Shirm”