Beam of Light: Stories

by John Kinsella

Author Interview at PaperbarkWords

“Then they heard the trucks buzz and ring, and – though it was a long way off – they knew a train was coming in … not a regular but an extra for the season … a big loading day tomorrow … And they were off, hopping over star-glinting track and flying down the blue-metal slopes and squeezing through the lifted rusted mesh of the barbwire-topped fence and back to their various homes … some near, and some more than an hour’s carefully mapped-out walk back. In through windows … quietly through back doors … all the tricks of evasion.”

(‘Reactionary’ in Beam of Light)

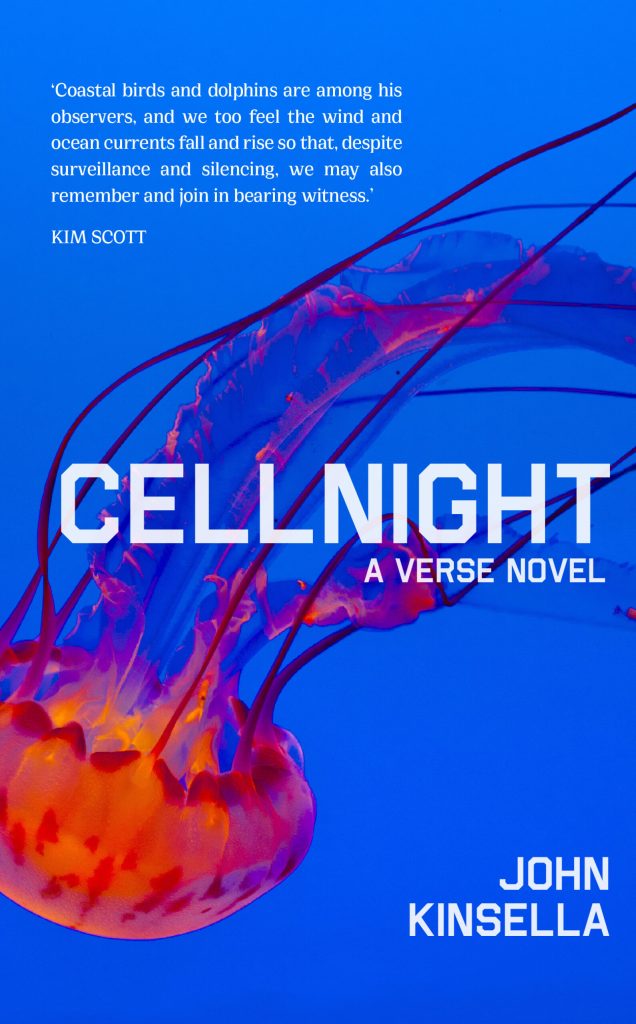

John Kinsella is one of our most eminent poets and writers. Based in Western Australia, his name is synonymous with the portrayal of landscape, particularly the conflicted status of the Wheatbelt region. His other books include Drowning in Wheat: Selected Poems, Jam Tree Gully: Poems, The New Arcadia: Poems, Sack, Night Parrots, Lucida Intervalla and Cellnight: A verse novel.

Kinsella’s new book of short stories, Beam of Light: Stories is a striking, sometimes uncomfortable, addition to his acclaimed body of work. The characters are flawed, often unlikeable. Some are stuck. Many are young. Every story has a hook to draw you in and keep you reading. Some of these hooks are indefinable but are there, nevertheless. Atmosphere oscillates between ominous high stakes, ambiguity and hope.

Beam of Light: Stories is published by Transit Lounge.

******

Thank you for speaking to ‘Joy in Books’ at PaperbarkWords, John.

As soon as I started reading Beam of Light, its quality as a literary work was clear. What element in your writing elevates it to this level?

I guess it’s an awareness of other literature. I am a lifelong, hardcore reader — I think reading is the most important thing for a writer — and that inevitably creates an awareness and brings responses to the idea of the ‘literary’.

You are well known for your poetry. Which of the stories in Beam of Light: Stories is closest to poetry or has poetic, lyrical elements? How or why?

I think my practice as a poet informs the way I process the world and therefore all my thinking and inevitably my writing. There’s the condensing and concentrating of language, of course, but there’s also often a figurative way of trying to interpret how people do or don’t relate to specific locations. I relish concrete details, and try to distil a ‘scene’ into a few sentences anchored in concrete detail, but I also look to add something metaphoric as well so we (hopefully) gain insight into what’s happening under and behind the surfaces. I am interested in showing exteriors and interiors almost at the same time, and the ’poetic’ serves this aim well, I think.

Why do a number of your characters spiral around obsession and addiction?

I have been sober for almost 30 years, but the 17 years before that were a wreckage of addiction and often mayhem. It was damaging to me, and damaging to those who loved me. We are only as ‘clean’ as the day we get through, and I am always mindful of that. It’s inevitable addiction forms such a focus of my fiction. I always try to find a way through the issues for my characters, but sometimes the circumstances overwhelm them, or sometimes they overwhelm themselves and others. Obsession and addiction intersect, but I am also interested in obsession as a positive as well as a negative — where it allows people to do things through absolute belief and commitment — though frequently obsession sways into self-damage and brings consequences for others. I try to consider all these scenarios and let the characters find their way through without judgement.

Some of your characters seem deliberately vague and remote in themselves. Recognition of one’s own disorientation must be difficult to communicate in writing. Could you give an example of why and how you’ve done this?

In the short story we can’t get to know all about a character, but we can get to know certain things intensely. I am interested in those intense moments as ‘windows’ through to the possibilities of the character. I can meet someone ‘in real life’ and have an intense impression of an aspect of their ‘personality’ and ‘behaviour’, but I know nothing about their broader lives, not really. And I try to convey this sense of things in some stories, maybe many stories. ‘Reactionary’ is one such example… say, a character (a train-tagging rural graffiti artist) who presents in one way to mask how they really feel: ‘Then he realised she was studying him real close, which he liked but it also irritated him.’ I try to let the story reveal this in short, sharp ways like this.

Landscape and setting are important in the stories. For what purpose and how have you ‘altered landscape’? (referred to on page 96, but please don’t feel restricted to this reference)

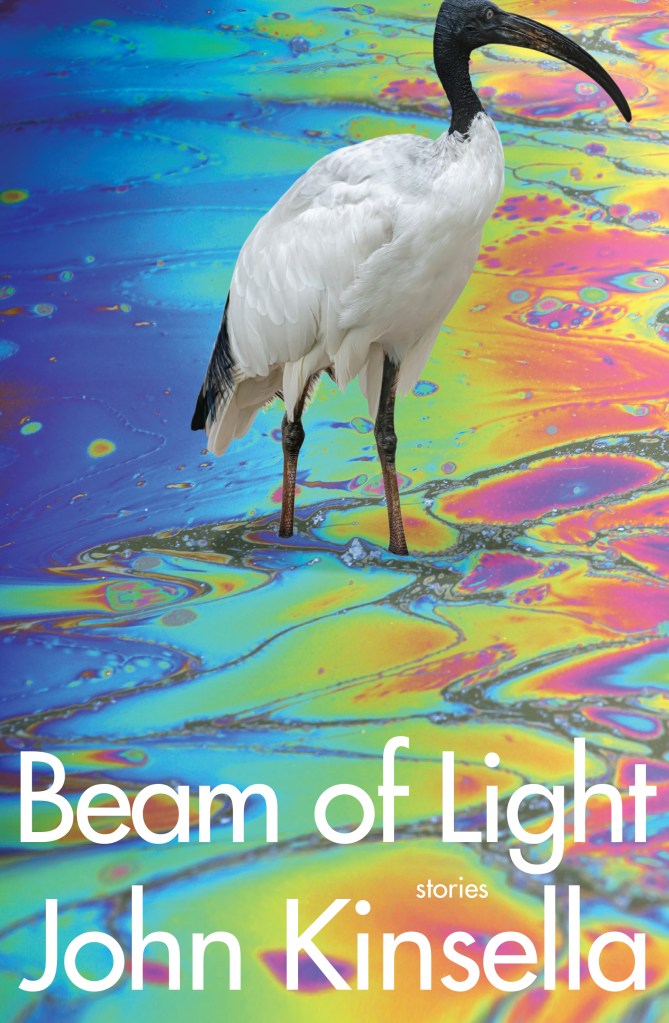

The cover actually interprets the detail of p96… the ibises in prismatic films of oil in wetlands. The land is constantly under pressure from developers, miners, loggers, industrialism and so on. I feel it is essential as an environmental rights activist to convey this pressure. My stories ‘chart’ the damage in the hopes of rousing a consciousness of how overwhelming and omnipresent these pressures actually are. The lives of the characters are necessarily affected by this damage, even if it is not overtly stated. Such changes bring changes to their lives, to the events I am conveying. I work through juxtaposing character with ‘setting’.

You place furniture in nature: the couch, a dining-room set. What do these symbolise or represent?

Good question. They always mean something! This is a corrosive colonial-settler image… the burning of an offensive past (to the burner) that in turn becomes an offence against the very biosphere. It should be added that the burner represents conservative reaction against what he considers ‘immorality’, which is actually based in anger for not receiving what he considers his material due: ‘They had loads of dough which they never did a day’s work for and they left it to some lefty charity – a save the something or other. But for their closest living relative, a bloody table and chairs.’

These kind of paradoxes fill the stories. There are no easy solutions to the crises colonial-settlerism has created. The stories use such symbols to suggest that nothing is without consequences.

Chickens, chooks and related expressions: playing chicken, accused of being scared, ‘chicken, chicken!’, chook farms and roosting and The Roost appear in your stories. Why?

That image is about the policing of masculinity by kids as ultimately imposed by school, social expectations and so on. The backyard chicken is a frequent urban nexus with rurality and becomes the symbol of the caged and controlled, the vulnerable (if often loved) and often exploited worker. Playing chicken is a proving ground that could lead to death: it yields nothing positive, just control and exploitation. I love all animals, and as an animal rights person always correlate the conditions of animals with those of humans. Chooks are highly exploited in the world (especially on battery farms…) and in some ways urban life for kids who don’t fit in (maybe no kids ‘fit in’!) is a bit like being controlled in such ways.

I know these are fictional short stories, but which one most reflects the essence of who you have been or who you have become? How?

None and all. They are extensions of my concerns and interactions in and with the world, though they are all fiction through and through.

Thank you, not only, for this tremendous short story collection, John, but for your incisive, generous responses. It has been a privilege to discuss some of these features of Beam of Light with you.

Beam of Light: Stories at Transit Lounge

Thanks to Transit Lounge for the review copy.