Isobelle Carmody &

Comes the Night

Published by Allen & Unwin

Author interview with Isobelle Carmody

‘Will marvelled all over again that people would try to stop their government building domes. Didn’t they know how bad the air was, how dangerous the sunlight? Domes were designed to filter both, and to screen out damaging radiation. Food grown outside was full of toxins. A bulletin last week had talked about terrible food shortages in countries where there was little doming. Then there were pandemics running through whole populations, which could be better controlled in domes where citizens were screened medically and regularly by their house and work hubs and treated for any illness. Dome-dwelling was obviously the only safe way to exist.’ (Comes the Night by Isobelle Carmody)

Isobelle Carmody’s Comes the Night is an enthralling, original epic. It is the best YA speculative fiction I’ve read in recent times and is good as the author’s best work. Intelligent, thoughtful and demonstrating respect for young readers, this novel powerfully traverses environmental and climate concerns, technology, fear and control, the importance of the imagination, creativity, the arts and history. It spans the emotional spectrum and is a mesmeric read.

********

Comes the Night by Isobelle Carmody

Thank you for speaking with Joy in Books at PaperbarkWords, Isobelle.

Your title Comes the Night makes readers stop, think and wonder. It’s an invitation into the book. What does it mean for you?

The title is very important. The naming of stories always is for me. I can’t properly write until I know the name of what I am writing. Comes the Night has a poetry and music that I like, with just a slightly inimical warning note.

It also incorporates a few important threads connected to the questions underpinning the story. I am often struck as a writer by how much of our creativity operates in and through our subconscious. In sleep, of course, when we process events of the day as dreams, whether we remember them or not. But it also operates continuously when we are awake, processing whatever matter it chooses beneath the eyeline of our conscious minds. I think the subterranean processing our mind does both when we are wake and asleep is tremendously important. When I mentor writers or run workshops, I stress the need to be conscious of the value of that process and to actively allow time for it. ‘Allowing time’ means not writing things down immediately, despite feeling enlivened by inspiration. It means thinking for a long time about a book or a story before writing anything, because written down, stories so easily become fixed by our efficient conscious mind. I think they need at first to remain fluid and flexible, capable of absorbing the world and of changing shape to incorporate new ideas. I urge people in this stage to think and think about their stories, to read around any issues or facts their stories involve, to talk to others – not necessarily about the story but about the ideas and issues it explores. I urge the asking of questions, the answers to which will invariably stimulate new thoughts. All of this enriches and deepens your story. Then the story needs to be left for a little so that it sinks down into the subconscious, either when you sleep or when you are busy doing other things. When at length you draw the story up to your conscious mind again, it will be saturated with material from the vast catacombs of mind that apparently hold memories of almost everything we ever did or saw. So the title Comes the Night references the value and richness and importance of those mental and imaginative processes that happen while we are thinking and doing other things. It also references the vulnerability of our subconscious to conscious manipulation by those who bypass our conscious intelligence and seek to affect our subconscious. One example of this would be the way political entities have sometimes weaponized fear via exaggerated media stories in order to create a populace that can be easily herded to whatever end is required.

I deliberately saved reading Comes the Night until a recent trip to Canberra, where it is set. It certainly made me more aware of the design and planning by not only Walter Burley Griffin but by his underestimated wife Marion Mahony Griffin, and reading the novel greatly enhanced my trip. Why Canberra and when in time is your story set?

I didn’t really think of a particular year, but I am imagining it is about 70 or a hundred years from now when some of the things that are flagged as dangers might have come to pass, and our technology had evolved reflecting societal changes. I wanted to see what would happen if that fear-mongering manipulation were not inhibited. I wanted to find out how much of our freedoms we might surrender to be safe, and what would then provoke a person to question and even challenge so called ‘protections’such as intense citizen surveillance.

As to why Canberra, it really had to be Canberra because it was when I was Emeritus Writer in Residence with UNSW and The Gorman Arts Centre, that I began to develop the story of Comes the Night. I was sort of given the keys to the city and for this reason, I saw things I would not normally see. I was taken down to the basement of the national Library and among other things, I was shown Marion Mahoney Griffin’s exquisite silk design for Canberra, which won the world-wide competition to design a capitol city. I was also invited to events at Parliament House where I saw illustrious performers like Olivia Newton-John rubbing shoulders with politicians and powerful men and women, and I saw quiet conversations where clearly serious matters were being discussed and maybe decided. I had this sense of the hidden corridors of power where decisions are made that affect all of us, without us being aware of how they are made, or for whose benefit.

Later I did some Post Graduate research on the Western Downs in small towns, and I found myself thinking about how designed towns like Canberra are trying to second guess the people who will inhabit them. Other towns grow up out of activities and need but designed town designers try to guess what people will need, and of necessity they try to control movement, so their designs will work.

That idea was interesting to me. The idea of architecture and city design aimed at shaping behaviour.

I really enjoyed how your protagonist Will follows his Uncle Adam’s clues around Canberra. Adam called these quests ‘The Wilful Hunt’ and we discover that they had a deeper purpose. Could you share one of your ingenious clues or something Will learned from these experiences?

I think the Wilful Hunt was set up to make Will attentive to his surroundings, and able to think in a non-linear way. The way the dreamscape works is by association, and Will was being trained to follow clues in a poetic dreamy language of symbols and poetic signs – what Ursula Le Guin so beautifully called ‘night language’. He was also being trained to imagine forward, not just to extrapolate or deduce.

As always, your worldbuilding is a highlight of the novel. What is something that particularly pleases or excites you about your world in Comes the Night?

I really love the idea of a dreamscape that is constantly changing and reforming depending on what happened in the day and whom you interacted with. I love the idea that a dreamer might not take their own form. That they might be their dreamscape or something within it. I love the idea that one might walk across such a landscape. In fact the idea came from a story I wrote called Perchance to Dream, and I loved that dreamscape so much I knew I would one day write a book that would allow me to develop it. In a way it is almost too rich. Literally anything could appear. I suppose the most interesting development from that initial idea is the notion that technology of an advanced kind might gain a foothold on the dreamscape.

I recall from our prior discussion that if you mention landscape or the weather in your work it means something significant. It could, for instance, reflect the interior state of your protagonist. How are you using landscape or weather to signal something in Comes the Night?

Oh yes this is absolutely true of Comes the Night. The fact that the weather is manufactured by a department. In the novel we never go outside. Not once. We remain in the designed bubble which like all walls is both a protection and prison, but there are many hints that some of what Will believes of the outside world might not be true – might be exaggerated as a way of ensuring people stay inside the bubbles where they are easier to control. Will begins the story living pretty contentedly inside the domed city that has been created, but by the end he is beginning to question many things, and the suggestion is that he is at the beginning of his own hunt for the truth.

In the novel how do you address environmental and climate concerns or issues of control and manipulation?

I think there are many things facing us that might qualify as dangers but the one that seems to me to be most troubling is the issue of misinformation. We cannot address any of the other problems if we cannot agree on simple facts, if we cannot speak to one another.

For Will and for Magda, imagination and emotion are how they navigate the web of lies around them. Both are driven by love and care for other people, to find out the facts. This might seem a bit beside the point. You might think I would say intelligence and education were what would save us from misinformation, but in fact we know that a person’s load bearing beliefs will not be changed by a logical or rational argument. However they can be changed by an emotional experience such as an incident that forces them to see something they were refusing to see. Art can also produce this sort of paradigm shift. I am not saying that facts are unimportant but if you are surrounded by clever competent untruths, how can you see that these are lies? Especially as in Will’s case, if he was born into those lies. I think that is where emotions and imagination can allow you to experience a sense of wrongness. Of course, then you must employ intelligence and critical thinking to learn what is really happening.

What do you believe is the place of young people in activism?

I am really interested in how young people like Greta Thunberg and others, are standing up to protest things they do not accept. The schools strikes where young people in many countries left school to protest the lack of government action on climate change, astounded me. I felt both heartened by their daring and courage, and, also afraid for them. Many adults felt this was not the province of children and young people, and yet they are the ones that will suffer the result of that inaction. So many things that we see as givens are not working for them, and they see it. The division of education into gifted, wealthy and low socio-economic categories, the huge and widening gap between the haves and have-nots, the funding of war – all of it seems wrong to them. They feel it and they have no way to be heard but by pushing against the systems around them.

Will is like many of us. He is comfortable and safe and he does not question what is happening around him until love forces him to search for information and that requires him to defy the rules. Ender would have protested with the school kids. She would not stay inside the domes. She would break out, and in her defiance, risk her life. For me, she represents that wildness in young people that many adults would wish to control or tame, and which is in fact a natural impulse to push at the womb and break out into the world – to push through the walls which are both an enclosure and a protection, to be free to be whatever she will be. She does not want to be safe.

Your protagonist Will is very well-crafted. Could you please list 3 of his attributes that make you proud of him.

Will’s kindness, his gentleness and humility are traits I really like. He is an artist, and so, part dreamer. He does not think he can save the world. He is full of doubts and he thinks a lot – sometimes that makes him passive, but when it comes to helping someone he loves, he is absolutely fearless. Most of all, Will is motivated by love.

How does he reflect young people today?

Will cares about things deeply. He is serious and creative and conscientious. He is not judgemental and can communicate with younger people and much older people as if they are individuals rather than age representatives. He is brave. I saw all these qualities in the fifty or so young people I worked with in regional towns on the Western Downs for over a year, in the My Future Town project, and like them, he has a powerful imagination.

The red kite, Lookfar, is an important, memorable and beautiful symbol in your story? Could you tell us something that you love about it?

Lookfar is a technologically sophisticated kite that Will was given as a gift by his uncle. It is a very beautiful kite that allows the person wearing its auxiliaries to experience flight as if they were the kite. But it also holds secrets connected to both the dreamscape, which Will gradually discovers. The kite connects the dreamscape/subconscious, to cyber space and ultimately to the potency of the imagination.

You have also organised the Hope Flies Kite auction for Red Kite.

Please tell us a little more about this – and how it ties in with Comes the Night?

When Comes the Night was completed, and I was thinking about publicity and appearances and talks, I felt like I would like to have something more to talk about than myself. I thought of running a fundraiser, and I was looking up fund raising bodies when I came upon Redkite. I was rapt to find it was a charity that takes care of families dealing with childhood cancer, because that is a cause that matters a lot to me. I once read to a young girl who was dying, and it had a very strong impact on me. I remembered how incredible her family had been, and it seemed to me that kites would work beautifully as a theme for the fundraiser – there is something so beautiful and hopeful and enchanting about seeing a kite flying – it is both captive and wild, and there is always the possibility that its string will break and it will fly free. I wrote to 30 illustrators and artists asking them to decorate a kite and they agreed. But when I tried to buy kites they were either horribly tacky – I could not ask people like Shaun Tan to decorate such a thing. But the good ones were way too expensive for me to buy 30, so I decided to make them. A metal sculptor called Al Phemister made me a prototype – an actual red kite, and helped me to work or how to do it, and between us, we produced 30 kites. Not real kites but kite-shaped canvases. The theme was Hope Flies, and the kites were really beautiful, and although they have flown now to their new oners (We raised $10,000) I want to share the art and I am planning to have photographs of the kites taken by the National Gallery official photographer blown up and mounted as part of a travelling installation that will include a little documentary film about the project. I would love to see the installation used as a setting for illustrators and artists to talk about their work. You know there is no single dedicated festival in this country to illustrators and illustration?

You have illustrated your excellent children’s books in the ‘The Legend of Little Fur’ and ‘Kingdom of the Lost’ quartets.

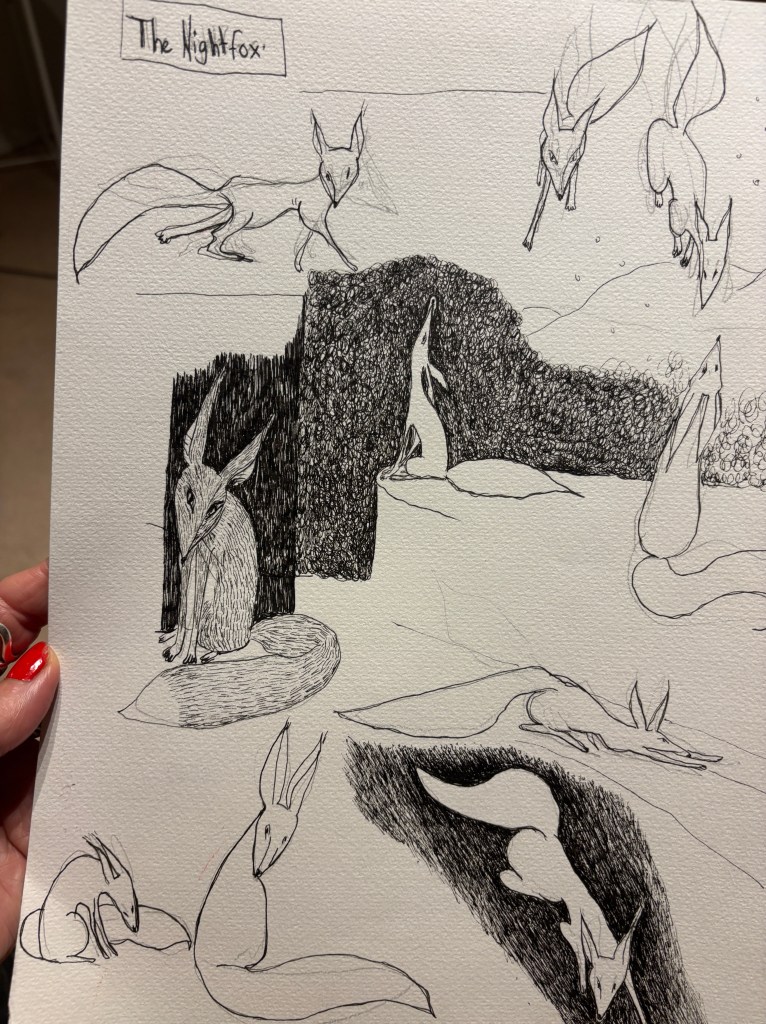

Cats and dogs are a staple across your books and play strategic roles in Comes the Night. It may be too big a request, but could we impose on you to quickly sketch an iteration of an animal that appears in the novel?

I believe that you have a heart for aspiring and other writers. What is a way that you mentor or help others in the literary world?

I run monthly workshops though my Patreon site, a yearly mountain retreat and I enjoy running workshops. At the moment, my workshop focus is on graphic story-telling, because I have been working for over a year on a graphic Little Fur novel for some time with a Canberra artist called Paul Summerfield, and I have been doing a lot of research into that form. It is not my frontline project so it will be a slow evolution. I am working on Darkbane, which is the final in a series I wrote a while ago. I really like to talk to writers for my sake as much as theirs, and I am pretty much always available if someone approaches me. I can’t read dozens of ms but if I have an interaction and feel I might be able to help, I might ask the writer to send a few pages. I am less good at structural editing than at helping people to write better – I think working and talking with other writers as well as reading broadly really helps me to grow as a writer.

Isobelle, thank you so much for your trademark generosity in answering these questions with sagacity and a big-heart. It is a privilege to host your insights into Come the Night at Paperbark Words.

Comes the Night at Allen & Unwin

*****

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

An extract from my interview with Isobelle for Magpies magazine (published in 2018, reproduced with permission)

Isobelle Carmody: Red Queen of Fantasy Writing

By Joy Lawn

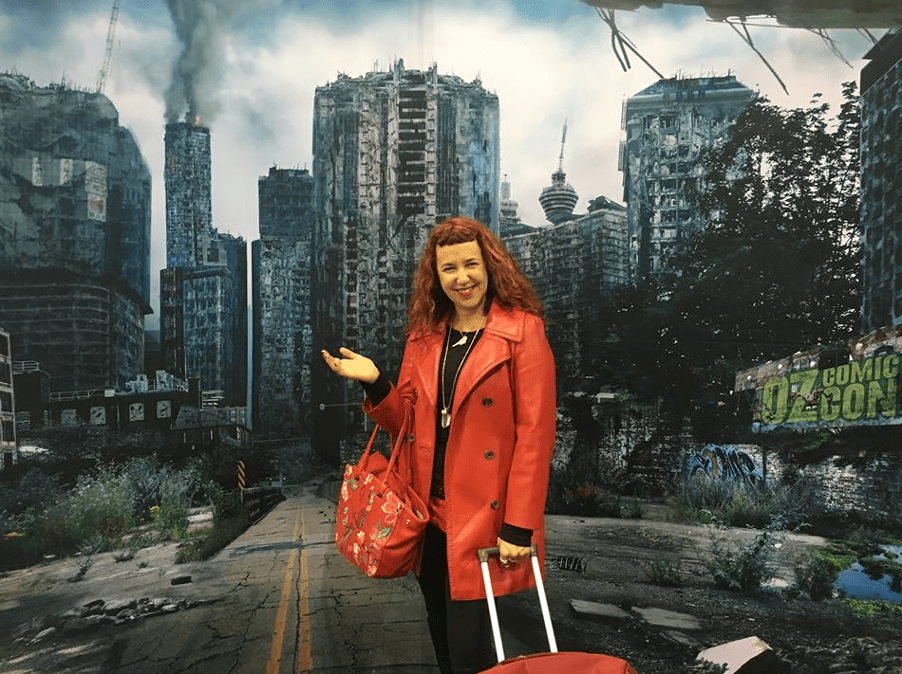

After her room-lighting smile and greeting, the first thing Isobelle Carmody says when we meet in Sydney for Oz ComicCon is, I love learning new things. This is evident from the vivacity and depth of her understanding and engagement with important philosophical questions. She is a whirlwind of enthusiasm and erudition.

I first met Isobelle in 2012 when I interviewed her with Justine Larbelestier and Scott Westerfeld in a session about Fantasy Worlds at the Sydney Writers’ Festival. It was a celebration, a memorable insight into contemporary YA speculative fiction by three of our best writers (if we include Scott as an honorary Aussie). The session was packed, it generated great excitement and feedback and I heard the comment as we left, Not just excellent but excellent-excellent. And everyone was sparking off each other.

The spec fic community of creators and readers is a unique, animate body whose fans are intense and loyal. They invest in their transactions with each other on the page, in person and virtually. Isobelle receives hundreds of letters and was teary over one long missive as we spoke. Many of the letters are articulate and written in high rhetoric yearning for beauty and channelling the terrible intensity of a fifteen-year-old. They write how I first wrote. Isobelle’s young adult readers align themselves with the young author Isobelle, who began writing her first novel, Obernewtyn when she was fourteen. It was published when she was in her early twenties. In their letters, readers echo the high language of Isobelle’s emerging work as they struggle to describe the ineffable. With the recent publication of The Red Queen, the ‘Obernewtyn Chronicles’are now completeafter thirty years.

Like her former panellists, Justine and Scott, Isobelle has strong roots in more than one place: she is known to spend half the year in Australia on the Great Ocean Road, which is home, and the other months in Prague. She is now based mainly in Brisbane due to her PhD commitments at the University of Queensland. Her PhD is called ‘Riding the Slipstream – The migration and metamorphosis of real world matter into the fantastic’. It looks at using the fantastic as a mode to explore real world questions in ways that are not available to realism. Isobelle explained slipstream [as] a genre close to realism, repurposing as a technique to connect real-world issues to fantastical themes, here with a focus on death. Fantasy can help those struggling to know the world and cope with sorrow. It can deal with mysteries such as death by moving back and forwards between what is real and not real. The genre of realism does this differently. The deepest things are ineffable. Fantasy can facilitate exploration of this.

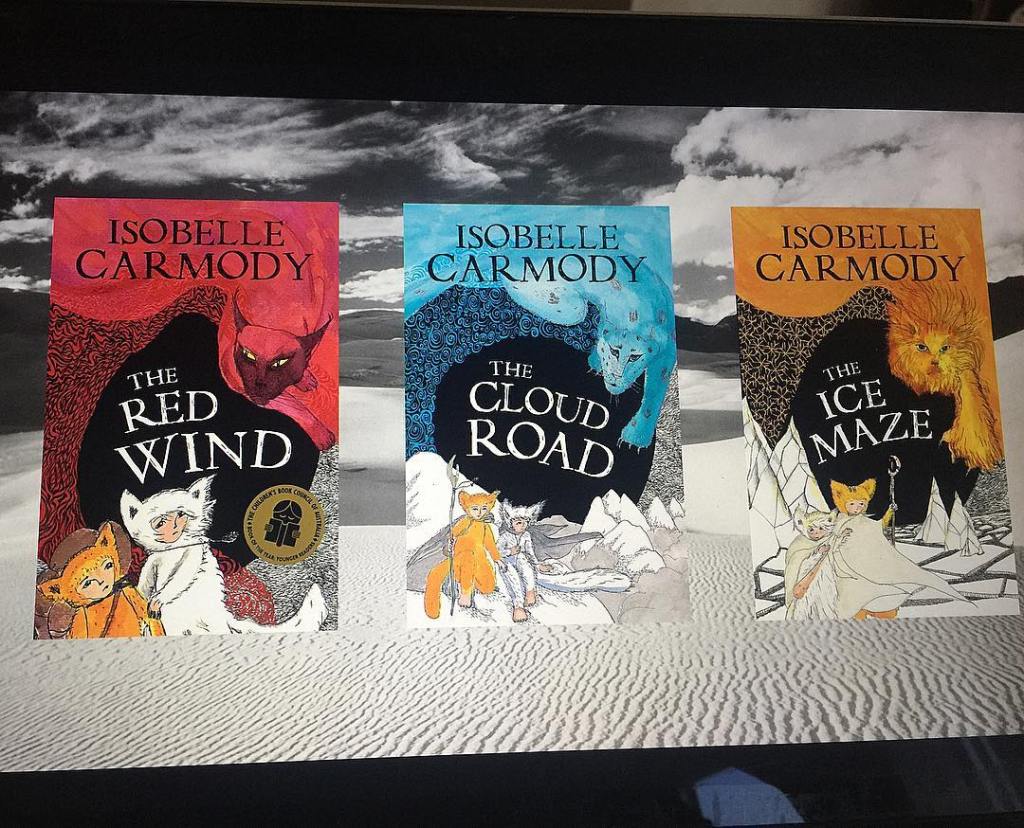

Through her author workshops, Isobelle knows that young people are concerned for the poor, the homeless and refugees. These groups can be seen as victims, but they may be brave and strong. Children also query when something seems to be natural but isn’t. Fantasy is used to address some of these issues in ‘The Kingdom of the Lost’, a dystopian series which has been published over seven years so far, beginning in 2010 with the CBCA winner The Red Wind. I heard Isobelle speak about The Red Wind in Brisbane in 2011 and particularly recall her affection for her two protagonists. The brothers have been changing and growing in maturity during the series with Bily enjoying their journey more and Zluty (like the author) appreciating Bily and his quiet courage, healing and artistic gifts, and goodness. The brothers share a dual narrative: an effortless, shifting point of view, which separates and comes together seamlessly. Isobelle hasn’t used this form elsewhere but here it emulates the utterly devoted, pure loving hearts of the brothers.

The Cloud Road was published in 2013, followed by The Ice Maze in 2017. The Velvet City and one other instalment is still to come. The plot is advanced in each book but more of the backstory is also revealed, such as the ‘diggers’, characters who made and then destroyed the annihilating stone storm machine, and the subtle positioning of the unnatural metal objects and poles. Human habit of throwing away what seems useless intentionally becomes part of this fantasy landscape. Place and characters develop so that, in The Cloud Road, Zluty can talk to the diggers better now because I think of them differently and by The Ice Maze he is so familiar with their speech and gestures, he emulates them inherently. Slavery and refugees feature allegorically and realistically in the stories, but Isobelle Carmody assures me that the diggers don’t represent Indigenous peoples.

‘The Legend of Little Fur’ is another series for children with environmental concerns, one Isobelle has also illustrated. She ensures the pictures appear on the page after the written words they describe and uses them to anchor sections. Like Bily, Little Fur is a healer with a missing mother. The elf troll is on a quest to discover her own heritage and her story gives children the opportunity to look at humanity from outside, through the eyes of a child.

The arts can be a source of healing. The arts heal. We should be nurturing art in the young, so they stay human. Isobelle Carmody writes as an artist, with a diverse, creative, forward compulsion. Alyzon Whitestarr, in the book of the same name, is musical: creative and unbalanced like her family. Her father explains the value of art-house movies, for example, in how they aim to put you off balance; to make you see things from a different angle. The arts have, often unrecognised, power.

Art represents healing in Isobelle’s work, but it can also be used to remonstrate, as she noted when writing The Red Queen, the final in her ‘Obernewtyn Chronicles’. Like most of her work, there must be change for growth. Change is life. Isobelle uses change to move the character to be a better person. Elspeth Gordie, like many great fantasy protagonists, is a misfit on a quest. Despite her, and the author’s, issues and concerns about the world, these appear in the work but are submerged for the sake of the story. Honour the story.

Elspeth is only one human, but she is a funnel whose powers allow her to step outside and into others’ minds. When later reading through the ‘Obernewtyn Chronicles’ meticulously for the first time from the character of Matthew’s viewpoint, Isobelle realised things that Elspeth had never known. I’d written a bottomless story. She had always planned to write the ‘Beforetime Chronicles’, prequels to Obernewtyn, to tell Cassandra and Hannah’s stories and is now working on The Book of Matthew. It will be a stand-alone novel to disclose what Matthew can see and cannot see but will also fulfil other characters’ stories.

The author’s recurring motifs of dreams and beasts first appeared in Obernewtyn and have continued to resurface in a number of her books, including Metro Winds, sophisticated short stories told through the lens of speculative fiction. Mythical cats also prowl through Alyzon Whitestarr, Greylands and ‘The Gateway’ trilogy, which began with Billy Thunder and the Night Gate. Now out of print, the rights to Billy Thunder will revert to the author and she will complete this numinous series with Firecat’s Dream.

Rights are important to Isobelle Carmody, particularly when her books go out of print or publishers want to commission fewer books in a series than she believes she should create. Ford St Publishing have revised and reissued three earlier stand-alone titles, Alyzon Whitestarr, Scatterlings and Greylands, a surreal, remembered world of child grief … [told] as a child would do – with poetry and imagination.Tara Morice, famous for the movie Strictly Ballroom, contacted her about adapting Greylands as a movie, with Isobelle to write the script. This is going ahead, although Isobelle has refused to allow the protagonist Jack’s age be moved from twelve to sixteen years for the purposes of marketing. Instead she will make him more gritty without being tougher.

Symbolic literary cracks appear in Greylands, Alyzon Whitestarr and ‘The Kingdom of the Lost’ series. In Greylands, Jack is warned not to step on cracks. Sometimes they are disguised as something else. A doorway, or a smile or even a winking eye. These cracks, rifts and crevasses open up a new way. There are things to be learned underneath. They also represent Isobelle’s interest in finding the core and truth of people and her characters.

Isobelle’s writing is often sensory: a melding of colours and scents. Place and the weather are of particular importance. When discussing this some years ago via email about Metro Winds and other works, Isobelle wrote, I think you will find that the stories in Metro Winds arise very strongly from my years in Europe – indeed the book has been ten years in the making – written over the whole time I have lived overseas. But with The Red Wind and The Sending, I think there is more a yearning to home and to something very non city. I am more and more attracted to ‘barren, unpeopled landscapes … I think place in writing can arise from your ‘where’ but I think it can also arise from the ‘where’ you are yearning after… and for me, landscape or place ALWAYS reflects the interior state of my main character – so does weather and nature – as if they are metaphors made real.

Her landscapes are often post-apocalyptic; her protagonists often empathetic. Contrasts and juxtapositions such as these deepen the work and enable an authentic engagement and transaction between writer and reader. These are marks of real literature. Isobelle is weary of so much slight and scatological humour in the children’s book market. Literature is being monetised as a commodity. She doesn’t like the commodification of writing. It’s a problem when publishers don’t keep backlists in print. She believes that publishers should maintain integrity and she values good editors and small, as well as large, publishing houses. Publishers and the Australia Council are doing a lot for young writers but it’s scattergun. Some of these writers are not ready. They’re dropped on their second or third book. Publishers may be missing the writers who need nurture.

However, Isobelle Carmody is still elated by writing. When I asked about the most important of her many awards, she cited The Gathering (perhaps my favourite of her work), which won the Peace Prize for solving conflict without violence. This, along with her legendary ‘Obernewtyn’ series and other fifty books, cement her standing as our gifted and greatly loved ‘Red Queen’ of fantasy writing.

Books cited in this interview

The Obernewtyn Chronicles Penguin Books Australia

Book 1: Obernewtyn

Book 7: The Red Queen

The Gateway Trilogy currently out of print

Billy Thunder and the Night Gate (2000) available Bolinda Audio

The Winter Door (2003)

Firecat’s Dream (forthcoming)

The Legend of Little Fur Penguin Books Australia

Little Fur (2005)

The Kingdom of the Lost Penguin Books Australia

The Red Wind (2010)

The Cloud Road (2013)

The Ice Maze (forthcoming)

The Velvet City (forthcoming)

Stand Alone Books

Scatterlings (1991) revised and reprinted (2012) Ford St Publishing

The Gathering (1993) Puffin Books

Greylands (1997) (2012) Ford St Publishing

Metro Winds (2012) (collection of 5 long short stories) Allen & Unwin

Alyzon Whitestarr revised and reprinted (2016 ) Ford St Publishing

Note: A number of Isobelle Carmody’s books, including those out of print, are available as Bolinda Audio books. Many of these are read by the author.

Complete list of works http://www.isobellecarmody.net/books/

Isobelle Carmody Website http://www.isobellecarmody.net/about/

The Garrett: Writers on Writing Interview with Isobelle Carmody https://thegarretpodcast.com/isobelle-carmody/

Sydney Writers Festival panel I facilitated with Isobelle Carmody, Scott Westerfeld and Justine Larbelestier

My review of Metro Winds (short stories) by Isobelle

2 thoughts on “Isobelle Carmody and Comes the Night”