GUS GORDON:

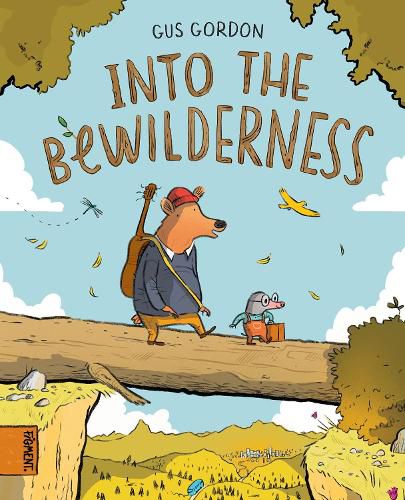

Into the Bewilderness

& picture books

Author-illustrator Interview with Gus Gordon, featuring Into the Bewilderness, at PaperbarkWords

“Is there more to this life? … Maybe we’re missing out on something here in the woods? What if there’s something else out there? Beyond the trees. Beyond the horizon, where the sun goes down into the ground for the night, and the moon is released from the big box, into the sky.” (Into the Bewilderness by Gus Gordon) (Hardie Grant Publishing)

Into the Bewilderness is Gus Gordon’s first graphic novel. It marks the next stage of his highly impressive and internationally acclaimed career in picture books and other children’s books.

This interview is a companion piece to our interview in Magpies magazine (July 2025). (The first question is reproduced from the Magpies article, with permission. The rest of the interview is original material for Paperbark Words.)

Thank you for speaking to ‘Joy in Books’ at PaperbarkWords, Gus.

Into the Bewilderness, your new book for middle-grade is a high-quality graphic novel structured in chapters. It is full of ideas and repartee between memorable characters. Why have you decided to craft a graphic novel as the next stage of your stellar career in creating books for young people? How has the concept and process to produce a graphic novel been similar and/or different?

The whole experience has been eye-opening, to be honest. I have learned an awful lot. I didn’t intentionally set out to write a graphic novel. In many ways, the characters I had been trying to write about forced my hand, in a rather organic fashion. This bear and mole have been around for 5 or 6 years. In those early stages neither of them had a name, but I kind of had their personalities worked out, and had been playing around with narratives for them, doing what I normally do with a picture book in mind. Generally speaking, when it comes to writing stories, I am always drawn first to the 32-page format, and the parameters around telling a story within its confines, but somehow this felt different from the beginning. Still, I tossed around my first vague scraps of a story with nothing more than the hope of a picture book at the end of the process. For some reason these two characters had a lot to say, especially the bear (he seemed to be already fully formed and was just waiting for a story to inhabit). Frustratingly, I had too many ideas and possible plot directions, and as hard as I tried, I could not wrangle them into something that might fit into a picture book, so I put it down for a while.

Sometime later, after sending my ideas to my agent, Charlie Olsen, I was chatting to him about my frustrations and he said, ‘I think this is a bigger story, Gus. Have you thought about a graphic novel?’ He is a big graphic novel and comic book fan and could see that there was the potential for a longer format story involving these two characters, and others too. This completely threw me in a spin, as I’d never considered writing a graphic novel before, and did not think for a second that I had the chops to do so.

Once I’d had time to process things, I realised that he was right (of course). This bear and mole deserved a larger story. So, I decided to sit down and write one chapter, and see where it led me. I did a lot of research, looking at other graphic novels, from here and abroad. I really hadn’t looked at many before, but I must admit that it felt familiar, in a sense, and once I began to flesh out the story, things kind of fell into place.

I began my illustration career over 30 years ago drawing cartoons, and comic strips for magazines and newspapers, until I was given an opportunity to illustrate a children’s book in 1995. So much has changed since then, and I still wonder how on earth I’ve managed to sustain a career doing something I’d do for free if I could get away with it. I think those early cartooning years taught me about the beats and timing of comic strip storytelling. The dramatic pauses, the spacing, the dialogue play, using the comedic foil to set up the gag etc. Also, like many children, I was an avid comic reader, particularly captivated by MAD magazine, Charles Schulz’s Peanuts, Walt Kelly’s Pogo, and later Patrick McDonnell’s Mutts, and Bill Watterson’s fabulously contemplative Calvin and Hobbes. When I began to write and illustrate Into the Bewilderness, I realised that this early love of comics would help me enormously.

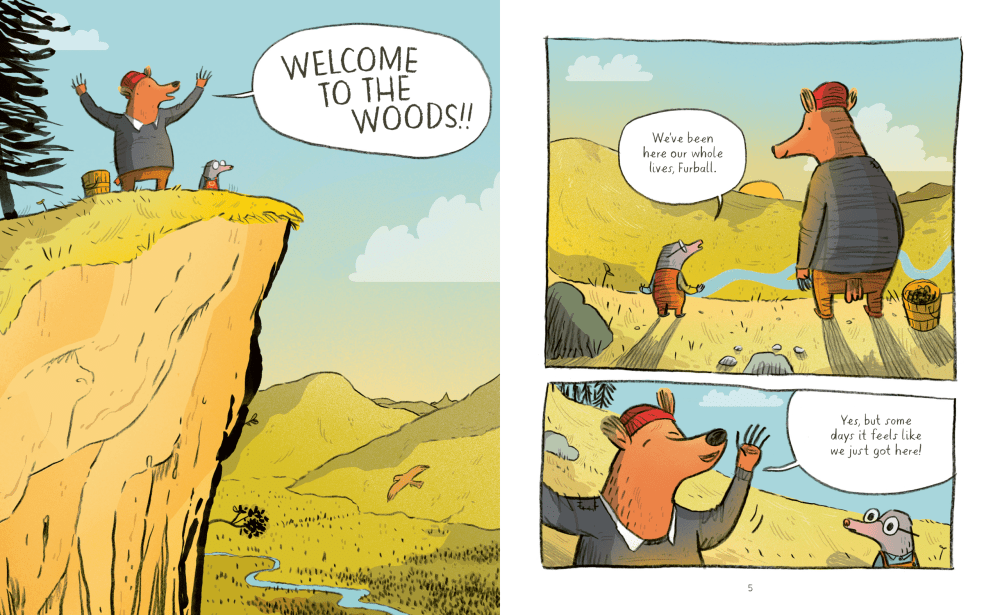

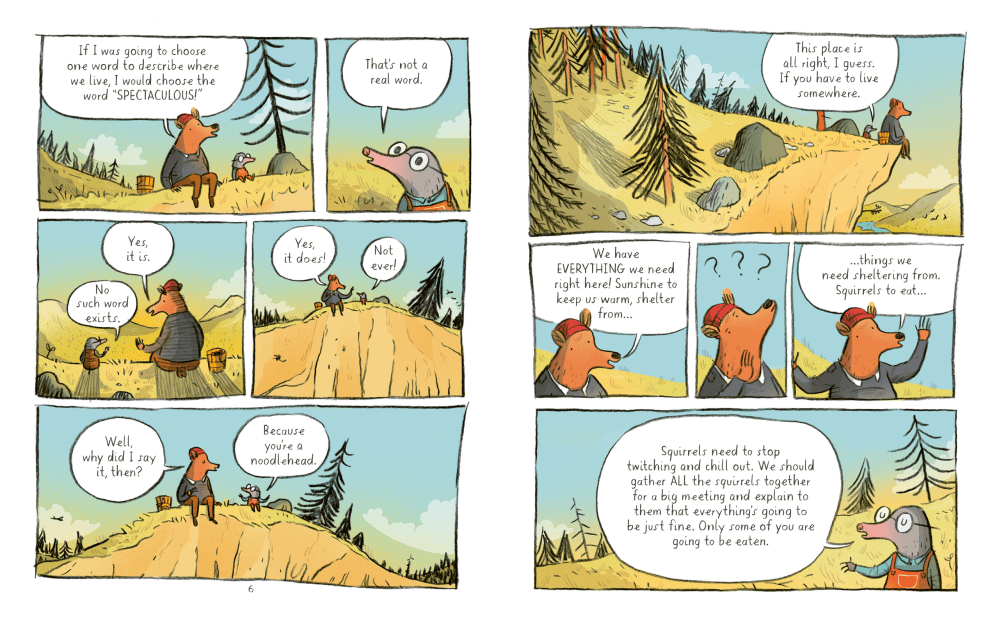

The wonderful thing about the graphic novel format is that it’s incredibly versatile. As long as the story is progressing, it doesn’t matter how you tell it visually. It embraces almost all the elements of storytelling. Much like a picture book, you can use the page space to breathe, and slow the pace down, not a single panel in sight. Perhaps a bird slowly making its way down over the forest below for pages and pages. Or, conversely, you can use multiple vignettes to speed the story up. A page full of panels as the characters debate something important to them. Much like a film director would, you are continually looking for the right beats, and the best way of telling the story, as if you were looking through the lens of a camera, the reader holding an invisible string as you pull them carefully through the story.

One of the most interesting aspects of writing Into the Bewilderness was learning how to write the ‘treatment,’ or script. It’s basically a screenplay-type outline of the whole story and it’s how publishers want to see it. I’d never done this before, and it was a bit of an education for me. It really made the whole thing feel like a movie, with everything broken down into scenes, including the character’s dialogue, sound effects, panel direction and art notes etc. Certainly, it was very different to writing a picture book manuscript, but fun all the same. It was refreshing doing something new.

Once I realised that writing and illustrating a graphic novel wasn’t such an overwhelming task (in the beginning at least), and I could potentially make it work, I had the confidence to persist, one small bite at a time. At my agent’s suggestion, I wrote the first chapter and put together a pitch for him to send out to publishers. Thankfully, we found a publisher reasonably quickly in the US (HarperCollins/Harper Alley), and in Australia (Hardie Grant/Figment).

Once, everything was contracted, I set about writing what would eventually be the other 9 chapters, with some welcomed script direction from my US publisher, Kait Feldmann. This came together surprisingly fast (for me, at least). All the time spent thinking about my characters paid off as they set about on their narrative adventures.

Has Into the Bewilderness taken longer to create than expected? Why? What was particularly time-consuming?

The whole process took over 4 years from the initial conception to publication. Everything was a long process. Writing the treatment, to drawing 200 pages of roughs, editing, scanning, alterations, choosing colour palettes, finals. Drawing the speech bubbles on separate pages etc. It really was a mammoth undertaking. I also dealt with some personal matters which slowed things down quite a bit.

You successfully anthropomorphise animals to create characters. In many ways you have formed the community in the woods (The Wild) realistically to emulate community in real life. How is the community here different from the usual way that community is shown in a picture or illustrated book?

The community in the woods is much the same, although I don’t explore this too much. As someone who only writes anthropomorphic stories, I never overthink choosing my animals according to cultural, gender, nor ethnic specific conventions. I stay well clear of stereotypical personality traits too. I just choose animals that feel right for each character. Of course, some animals are naturally more appealing than others (bears and pigs for example) and evoke particular feelings quite quickly, but I try not to give it too much thought. It’s always an illogical melting pot of animals from every corner of the planet, and I guess that pretty much represents the world we live in.

How have you used panels?

It all depends on what’s going on in each scene. Overall, I wanted to have as many big panels, or full bleed illustrations as I could to show the beauty, and vastness of their woods. I really enjoyed drawing all the outdoor scenes, and I didn’t want a book full of tiny boxes.

Why do you have small insert panels when the characters are talking? [eg p8,10]

It’s just a nice way to insert the dialogue, allowing the greater illustration in the background to breathe, and take centre stage.

Could you explain how you have composed or constructed panels to show hyperboles or imaginings? [pp51-6]?

Separating the present scene and the imagined scenario with a dotted line seemed to do the job of indicating that each character’s story about The Big City was in their minds only.

What was a technical difficulty that you faced in illustrating Into the Bewilderness? How did you solve it?

Trying to find ways to fit all the text into each panel was difficult at times, especially when the visual depiction was so fundamentally important for the reader to understand what was happening in the story. These issues were only solved by drawing countless roughs until I worked out the easiest way to squeeze everything in. Sometimes I wished Luis wasn’t so verbose (so does Pablo).

Your lines are arrestingly sharp and clear. Why?

Thank you! I don’t really know why. I guess it’s just my style. I always use the same equipment; a black Prismacolor pencil on 210GSM acid free watercolour paper, and a brush with Indian ink. It works for me.

Tell us about the lettering. Is it handwritten or a special font?

It’s both, really. I handwrote all the letters, numbers, and various symbols etc, and my US designer, Celeste Knudsen, made it into a font. It saved an awful lot of time!

What is something readers may not notice or be aware of at a first reading of this book?

The number of birds observing the action from above.

Picture Books

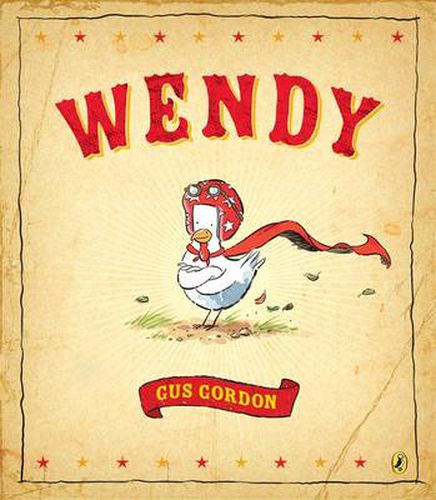

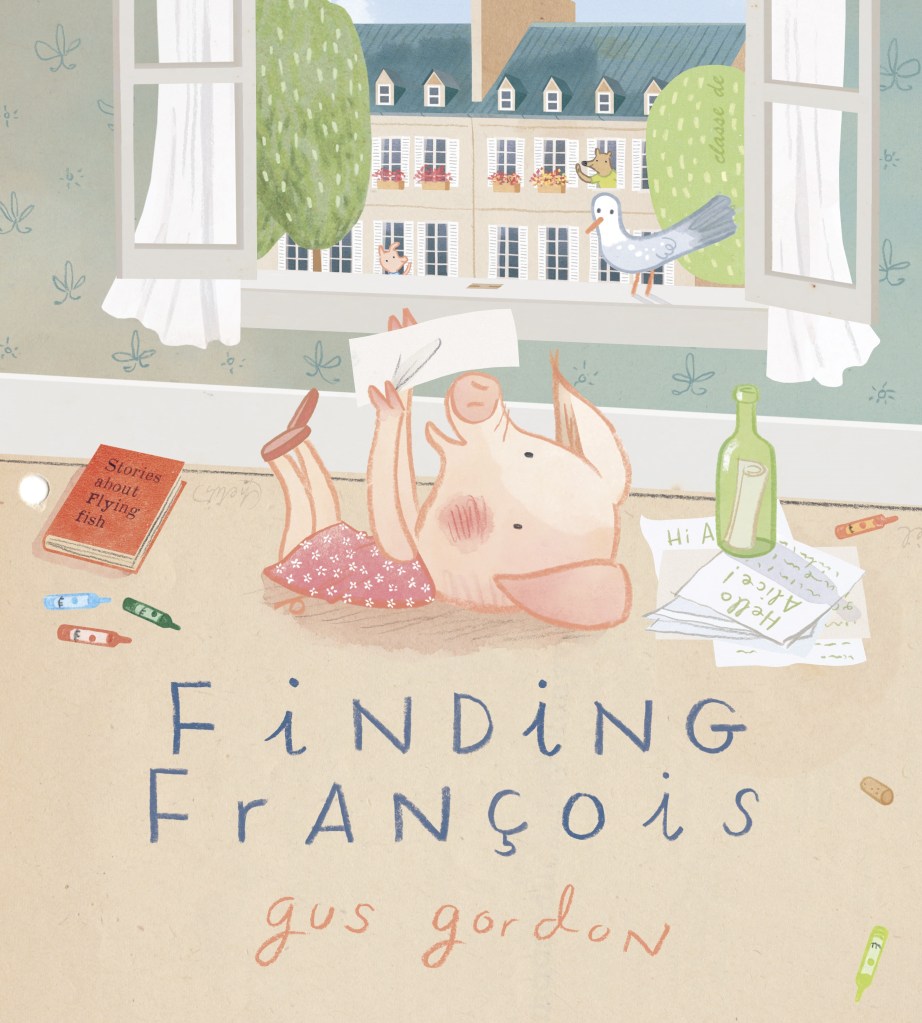

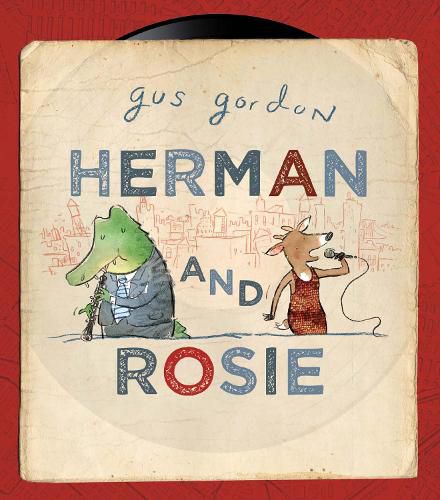

Let’s consider five of your significant picture books: Wendy (2009) – and I was privileged to be on the CBCA judging panel that gave it a Notable award), Herman and Rosie (2012) Somewhere Else (2016), The Last Peach (2018) and Finding François (2020).

You have drawn human figures in your earlier collaborations with other authors. Why are the characters in your picture books always anthropomorphised?

For several reasons. Firstly, I grew up on a farm, so we had a strong connection with animals and their lives. I have always been fascinated by animals. Naturally I enjoyed drawing them. As a child, some of my favourite books featured anthropomorphised animals. The Wind in the Willows was a cherished book, Enid Blyton’s animal stories were great, Winnie the Pooh of course, but it was Richard Scarry’s ‘Busy World’ books that really lit me up. I pored over them and was mesmerised by his playfulness, his sense of fun, and his ability to choose animals that suited his stories. Many years later when I began writing my own stories, it just felt like a natural fit. Children are drawn to animals, and in many ways when a character is an animal, you’re already off to a good start before you even begin to tell the story. The added bonus is that animals allow you to cover controversial or sensitive themes (death in my book Finding François for instance) in a more forgiving manner. They soften the blow.

What is it about France that has inspired you to set some of your books there (or make reference to it)?

I’m a tragic Francophile. I have always been a lover of all things French. Paris is especially wonderful. I have spent a great deal of time there, wandering the streets aimlessly. The French have such a wonderful, respectful relationship with the arts. It means a lot to them. They understand how important it is and embrace it as a big part of their cultural identity. It’s in their DNA, and I can almost feel it in the air.

You have often used collage in your books. How does it enhance your work? What can it do that other forms of illustration can’t do as well?

Collage is my favourite medium. It’s really the only medium that has the ability to contribute to the narrative. To tell story within story, both visually and contextually, and thereby strengthening the overall narrative. I use it carefully as I want to make sure that the collage elements don’t distract the reader from the story; rather it provides a layer of whimsy and visual interest. That’s the tricky part. The last thing you want is for the collage to pull everything apart. Good collage is a visual treat for the reader to take in over and over. Much of my collage materials are obtained from old French shopping catalogues and from Parisian markets, and a fantastic store in Paris called La Galcante, in the 1st arrondissement.

What are some of the signs, devices or features in your picture books that hinted that you might create a graphic novel in the future?

To be honest, I don’t think there have been many obvious signs. Perhaps the fact that my last book, Finding François, was the first time that I written a picture book that was 40 pages long, rather than the more prevalent 32 pages. I didn’t really see this graphic novel coming, but I’m glad it did. Having said that, I’m quite happy to go back to picture books for a while.

Why are friends, community and home prevailing themes across your work?

Home is always a powerful notion in stories, and it features heavily in Into the Bewilderness, as I mentioned earlier. A familiar theme that has been pointed out to me from readers, as a recurring feature of my stories over the years, is the theme of loneliness. That in the end we are alone in this world, and despite the undeniable importance of family and friends, it’s up to us to make the most of our short lives. I don’t really know why I keep coming back to this motif, but I do. It’s something we are all cognisant of, especially as we get older.

What other themes, concerns or human qualities close to your heart have you featured over the years?

Aside from music, it’s quite easy to note that well-rounded, recognisable characters are the most important element in my stories, whether it’s a daredevil chicken, a lonely duck, or an oboe playing crocodile. I spend a lot of time working on characters, and then hope, when my book is out in the world, that they connect with my readers.

What award has meant the most to you?

I think when Herman and Rosie won the CBCA Honour Book award, it made me feel like a legitimate writer for the first time. The self-doubt we have, in any creative pursuit, can be overwhelming at times, and for years I felt like I’d be ‘found out’ and dragged off to the building where they keep embittered writers. I feel incredibly fortunate to still be doing this after so many years.

One thought on “GUS GORDON: Into the Bewilderness & picture books”