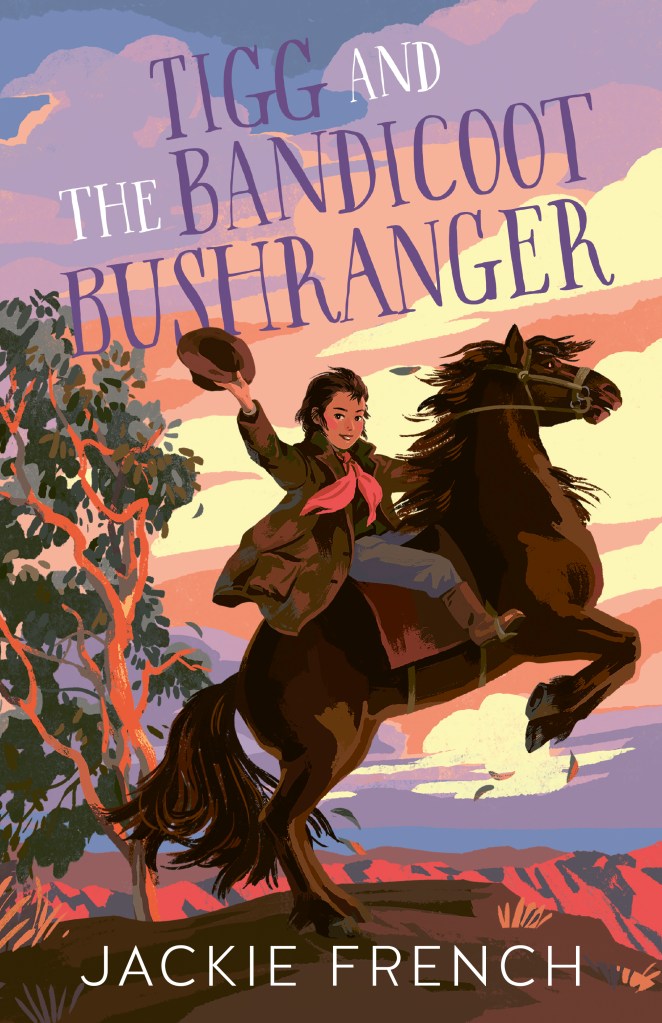

Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger

by Jackie French

(HarperCollins AU)

“It wasn’t easy being the smallest bushranger on the goldfields. It was worse

when your borrowed horse ate your wig.” (Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger )

Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger by Jackie French is shortlisted for the 2025

CBCA Book of the Year: Younger Readers.

Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger is a lively, historically accurate account of

Australia’s goldrush and bushranging era with a focus on the Long Walk.

Visceral, sensory, beautifully written and packed with interesting facts and

experiences, Jackie French brings this time, place and characters to life.

Congratulations on Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger being shortlisted by

the CBCA, Jackie, and thank you for speaking to Joy in Books at Paperbark

Words blog.

Author Interview: Jackie French

You have deservedly had many books shortlisted by the CBCA (and other awards) over the years. Which recognition by the CBCA (apart from Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger this year) has meant the most to you, and why?

I treasure the memory of the year my husband Bryan Sullivan and I won the Eve Pownall Non-fiction Award for To the Moon and Back, standing on stage together, with Bryan in his best suit instead of his usual jeans and daggy ‘work’ jumper. Bryan’s Alzheimer’s is progressing. Every day with him is still a joy, but he keeps that book, with the award sticker, both by his bed and his favourite armchair, to remind him of the days he helped give humanity the moon to wander in, and the years we spent writing the book together.

This is a poignant and powerful memory and outcome, Jackie. Thank you for sharing.

Could you please introduce your 2025 CBCA shortlisted novel Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger by telling us something about the Long Walk.

Victoria discouraged Chinese ‘diggers’ in many ways, partly by heavily taxing them on entry. Many walked from Sydney or Robe in South Australia. Later, the White Australia policy would prevent many from entering at all, like my beloved neighbour and mentor Mr Doo who walked from Cape York to Charters Towers to mine, then from Charters Towers to Brisbane to market garden.

Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger is obviously historically rigorous and authentic. What piece of information did you uncover that surprised you?

I knew of anti-Chinese attacks and slaughter like that at Lambing Flat, but had no idea how many Chinese people died, or of the exact records. Of over 250 arrivals just north of Sydney, for example, only forty-nine made it to the ‘protectorate; in Castlemaine, created as a place of safety for Chinese.

I also learned there was no ‘one long road.’ History is so often simplified. A single ‘long road’ would have been dangerous, and floods, drought and fire affected the route taken too. There were possibly hundreds of routes, though most routes did incorporate at least one Chinese market garden, and more if possible. I found evidence of one such ‘hidden’ market garden near my property, well away from the road, with a water race carrying water for irrigation from kilometres away. Some of the old crops and fruits brought as seed from China still grow wild there.

How have you combined historical accuracy with writing a gripping tale?

That answer could take a book, or a sentence. This is the sentence, but it can’t explain the thrill of research, of reliving the adventures as I write, or the joy of adding piece after piece to the jigsaw.

I imagined gripping characters who might have been at that time and place and worked out a reason why one might do the ‘long walk’ – someone who was not Chinese, and so would need everything explained to her, as well as the reader.

Why have you chosen Tigg and Henry Lau as main characters?

Tigg must know nothing, so the reader learns as Tigg discovers the world around her. Henry must understand it all, so he can explain, as well as being able to speak English.

How do you get us as readers to be so quickly and wholeheartedly on Tigg’s ‘side’?

The first two sentences (quoted above) are vital: they show us that Tigg is young, in a world of adults; courageous enough to be a bushranger; adventurous; resilient; loves animals; and has a sense of humour.

One of the minor yet pivotal characters is Ma Murphy. Could you briefly describe her?

A survivor, in a world where it was hard for any woman to survive without a male protector.

You’ve incorporated plenty of humour into the tale. Could you give an example of a favourite example?

Miss Eugenia “Dear Papa would never let us read fiction’ she said wistfully. He thought it might give females ideas.’

As indeed it does.

How does ‘identity’ become a key idea in the novel?

We assume people are from a certain race by their appearance. In reality, unless there is a major clue like a distinctive physical characteristic, we use their clothes, their attitude, their way of talking and much else to identify them. It can be surprisingly easy to appear to have a different racial or cultural background.

Like many Australians, my ‘racial’ background is deeply mixed. Who am I? I don’t claim identity from my genetic background, but from the culture everyone assumed I belonged to, ‘white Australian’, even though many of my ancestors weren’t white.

How have you included or represented First Nations People or Country within your story?

Knowledgeable, compassionate, willing mentors – and living precariously on the margins of greedy white colonial society.

Your writing about the Australian bush is suffused in understanding and appreciation.

What do you love about the bush?

The bush is endlessly generous: there have been times in my life when most of my food and shelter and much less had to be gathered from the bush around me. It’s ever changing. I can walk the same track for 50 years, and it will be different every day. Cities are simplified: all angles and hard surfaces, the creation of only one species, us. They’re boring and unchanging and slightly frightening: you need money just to eat, or to sleep in a safe shelter. The bush is infinitely generous, once you understand country, and always fascinating and unexpected.

How is healthy fresh food integral to the characters’ lives in this book?

Fresh food is life or death. Starvation and deficiency diseases like scurvy or pellagra killed far more than bacterial or viral conditions, or dangers like floods, fires or venomous snakes. We would not be a thriving nation without the knowledgeable Chinese market gardeners our governments tried so hard to keep out. Even in my Brisbane childhood, fresh food came from a Chinese market garden, and most suburbs had one, even near Central Sydney.

How do you think historical fiction helps us or leads us into the future?

How can you know where you want to go if you don’t know where you’ve been? History teaches us who we are as humans; it shows us resilience, and how to survive but in safety: the volcano or tiger vanished when you shut the book covers. Mostly, historical fiction helps us understand humanity in all its variations. We learn how people changed the past, so we can change the future of humanity, so we survive. All of us have only one life: but when we read books we absorb the experiences and wisdom of thousands of people in hundreds of times.

Athletes train for bigger and more effective muscles. Historical fiction builds our capacity to imagine, and create.

Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger certainly shows how historical fiction enlightens and helps to lead to lead us into the future. Thank you, Jackie.

Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger at HarperCollins

My interview with Jackie French about Secret Sparrow at Paperbark Words blog

One thought on “Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger by Jackie French”