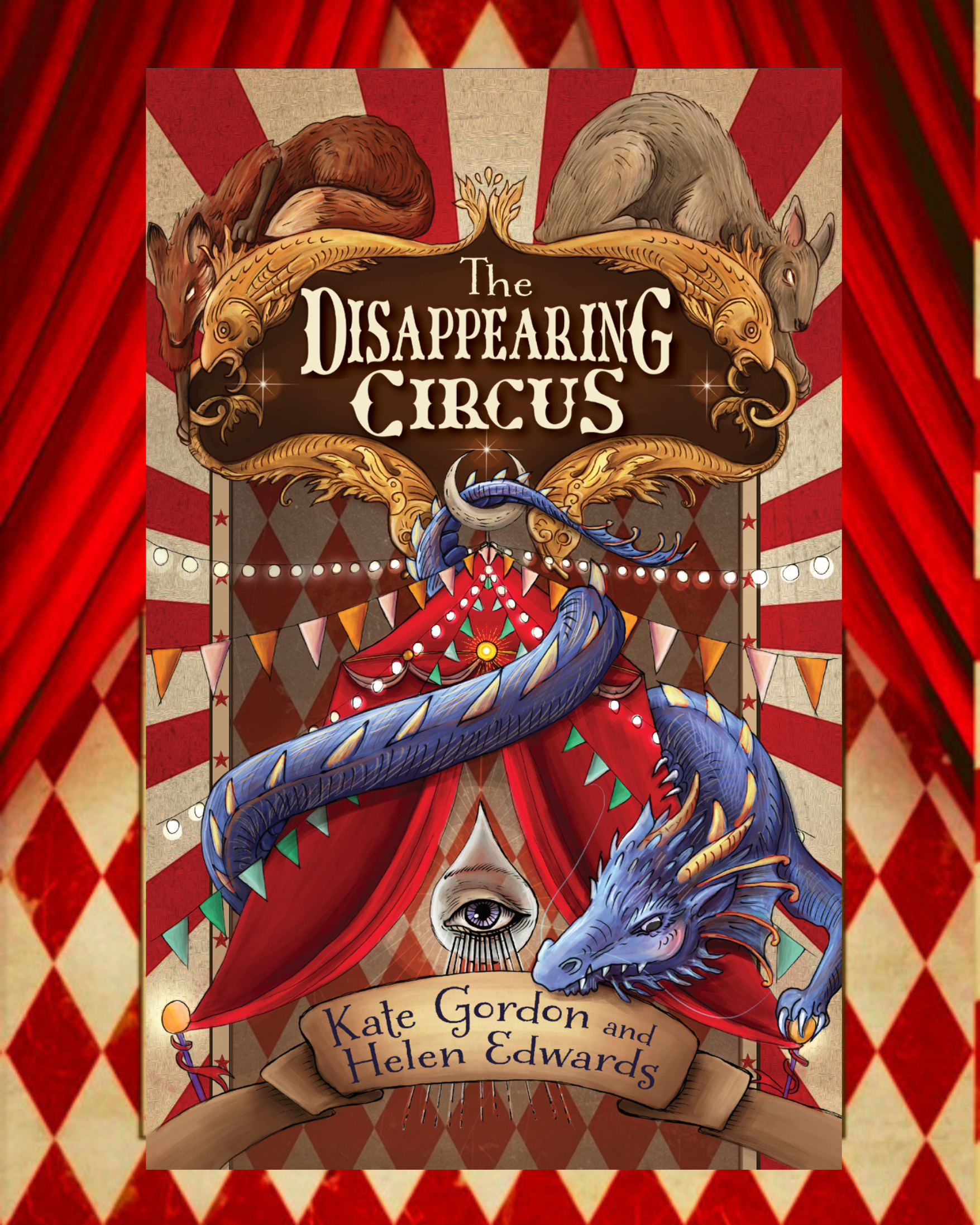

The Disappearing Circus

by Kate Gordon

and Helen Edwards

Published by Riveted Press

Congratulation on your new book and thank you for speaking to Joy in Books at PaperbarkWords blog, Helen.

Author Interview: Helen Edwards

Being the Hero of Your Own Story by Helen Edwards

When Kate Gordon and I became friends online some years ago, we quickly realised we had much in common. I had long-admired Kate’s work and held a secret dream to co-write a book with her one day.

Unbeknown to me, in 2023, our mutual publisher Rowena Beresford from Riveted Press had given Kate an early copy of my debut middle-grade novel The Rebels of Mount Buffalo. Kate says that when she read that manuscript, she realised we had a lot more in common than we knew—it was like we had the same writer brain. When she approached me to co-write a book, I was of course, delighted and said yes please!

Lots of people have asked us how we wrote The Disappearing Circus together when we live in different states—me in Adelaide and Kate in Hobart. My response is similar to the one I used to give people way back in 2002 when they asked me how I was offering online counselling to people with diabetes—something that was then in its infancy—using the internet! Yes, despite all of the dangers and negative impacts on our lives, the internet and all of its associated tools, offer writers like Kate and I, an easy way to collaborate on a project.

I do think you need to be well-matched to work in this way, have an easy communication style and be open to feedback from each other. You need to understand when one or the other has a need for a pause, or on the flipside, when one or the other wants to forge ahead. You need to be good at communication by written word, which is luckily something we both enjoy. You also need empathy and genuinely like and care about your co-writer. Kate and I already had those aspects to our friendship, and through the process of writing together, we have learned more about each other and become very good friends. We have now written a number of other manuscripts together, with the first in our new junior fiction series coming in August 2026. I can see us writing together and being in each other’s lives for many years to come.

Enter The Circus

When Kate and I agreed to begin our first writing project we bounced around ideas for a story. I listed a number of themes I had been considering myself and one of those was a story set in a circus. Kate told me she had an idea for a dark sort-of circus that had been in her mind for a while, and our setting was chosen! From here we developed our characters—Emme and Ivy—a brief outline of a few aspects of the story and our characters, and began writing.

When Kate and I write together, it is like musos riffing off each other, or screen writers in the writing room—we bounce off each other’s chapters, back and forth, until we need to stop and discuss something. If one of us feels there needs to be a change or a different direction, we stop and go back.

As we worked through this particular story, we had a number of things to address. One was the time period and as it is a fantasy world, we needed to decide if it had the feel of being back in time, ahead, or in current times. I was keen on the idea of disappearing animals connecting to the loss of species in the here and now, as well as the inclusion of extinct animals in the circus. But this also needed to fit with our olde-world feel.

The world-building took some re-development after draft one, as we are both pantsers and needed to agree on aspects of things like transport, technology and language. We also had to wrangle all of the mythological and extinct animals, as our free-form style resulted in an overly full Big Top! We made lists of our creatures and whittled them down into something manageable. In later edits it was important to ensure Ivy and Emme had distinct voices, but also that they flowed together to make a seamless story. The Ringmistress Seraphina and her dark secret also needed refinement. It is a complex story.

An Allegory on Hope

Kate and I both address similar themes in all of our books, including neurodiversity, disability, grief and hope. We wanted to write a story together that would leave young readers feeling hopeful about their future.

In many ways, this is a story about loss and grief. It tells the tale of two girls who are running away from their lives due to the burden of their sadness. They are dealing with their losses in different ways, with different levels of self-confidence. When they find themselves flung together in a world like no other, they learn to believe in themselves and each other, and to see that they are loved and never forgotten.

At its heart, The Disappearing Circus is an allegory on Hope—on the many ways we can hold onto hope despite the hopelessness we may face when we look out into the world. Young people need to know that they are loved, seen, and understood. They need to feel empowered to change and impact their own lives.

In the strange and magical world of The Disappearing Circus, they might just see that they can be the hero of their own story and that the whole world is their stage.

The Disappearing Circus at Riveted Press

Other Resources

Kate Gordon’s Whalesong at PaperbarkWords blog

“Tiny Moments of Joy” interview with Kate Gordon by Joy Lawn for Magpies magazine

May 2022

(reproduced with permission)

Joy Lawn interviews Kate Gordon about her books for children

Even though there is sadness. It’s not all sadness, and the sadness there is doesn’t feel like it’s without hope. That’s the things about being a kid, in books at least. There’s still hope. There’s always hope. (Aster’s Good, Right Things)

How incredible and profound is children’s literature. As Kate Gordon shows in her books, it can shake us upside down, put us in the shoes of others and open our hearts.

Kate Gordon’s Aster’s Good, Right Things (Riveted Press) won the CBCA Book of the Year: Younger Readers in 2021. It is an exceptional novel: a beautifully written and sensitive portrayal of childhood anxiety. This, and its sequel Xavier in the Meantime,are reminiscent of Glenda Millard’s Kingdom of Silk series where lyrical writing and sensory imagery create wistfulness, melancholy and pain alongside beauty, hope, light and tiny moments of joy. Both authors address serious concerns in the lives of children, with Kate’s books having a more sorrowful core.

Kate also writes for young adults (Girl Running, Boy Falling is a standout) and younger children (Juno Jones) but in this interview we will focus on her books for older children: her books about Aster and Xavier (Riveted Press/Yellow Brick Books) and her Direleafe Hall series (University of Queensland Press)

Thank you for speaking to Magpies, Kate.

Your novels Aster’s Good, Right Things and Xavier in the Meantime show deep understanding, concern and care for those with anxiety and depression. Why have you written about child characters with these illnesses and how have you crystallised something of these conditions into stories?

As a child growing up with intense anxiety and, at times, severe depression, I never felt comfortable expressing what I was going through, because it didn’t feel “normal”. Nobody I knew, none of my friends or family, seemed to feel like I did. I was incredibly isolated, especially in primary school, because I seemed to think differently – and definitely behaved differently – from the other kids around me. Now I’ve been diagnosed as autistic, I have some answers for why this was but, at the time, I felt like a “freak”. None of the adults in my life thought there was anything to worry about, because I excelled academically and in extra-curricular activities, and the prevailing wisdom around autism and mental illness in the eighties and nineties would have said that being autistic and academically gifted did not go hand in hand. None of the books I read or movies I watched spoke to me. I never saw myself reflected in the media. Now, it’s a passion and privilege of mine to write books for kids like I was, so they know they’re not alone and they’re just as “normal” as anyone else.

How do you balance sadness and pain with moments of joy in these two books?

I mean, that’s life, isn’t it? Joy and pain and so intrinsically linked, it would be impossible to feel one without the other. When I’m writing, I’m just trying to write life and so often in life happiness and heartbreak can coexist in a single moment. The same should be true for literature or else it doesn’t feel real.

Your Direleafe Hall books have a Gothic atmosphere. The three major protagonists and the crow Hollowbeak live in and around Direleafe Hall, an old school building that is home to its inhabitants, and they are surrounded by ghosts. Why have you set these stories in the supernatural?

I guess living very deeply in a fantasy world for my entire life means that the “real” and the “magical” don’t feel at all separated for me. I have a very strong belief that the things we call “magic” are just as real as anything else. I have a daughter who is nearly ten and her interior world is just as much a part of her ordinary life as school and friends and playgrounds and dinners. I believe in ghosts. I believe in the afterlife and reincarnation. I really, deeply hope unicorns exist in some secluded forest. I live in Tasmania and it’s impossible to travel through this state without feeling the ghosts of its past, walking beside you. It’s impossible to look up at kunanyi without imagining the supernatural beings that might live amongst the dense trees. The entire south west of our island is largely untouched wilderness. Think about all the creatures that might live in the undergrowth. Magic is all around us and to write the “real” set down here is, by definition, to write the magical.

Apart from the setting, what threads link these three books?

I feel like the thread that links all of my books is something to do with loneliness and something to do with hope. Something to do with isolation and seeking – and finding – belonging. It’s such a powerfully human thing to yearn to find the place where we fit in, and all of the books in the Direleafe and Aster series are about this. It’s also a powerfully human thing to wish to be seen, somehow. Whether it’s being a ghost who wishes to be seen by humans or an autistic kid who wishes to be understood, it’s a universal feeling and it’s definitely present in all of these stories.

You obviously select the names of your major characters with great care. Could you please introduce Wonder from The Heartsong of Wonder Quinn and Melodie Rose from The Ballad of Melodie Rose and explain the significance of their names?

I wish I could have some deeply intellectual answer for this, but the truth is that the characters often come to me with their names. Wonder was Wonder from the moment I “saw” her, travelling through the Midlands of Tasmania, sitting atop the ruins of an old school. Jackdaw was always Jackdaw. The only one who changed was Melodie. To begin with, she was Elodie, because it was a name I always loved – and it sounded so musical to me. As music is very important to Melodie, it seemed to make sense. Somewhere along the line, Elodie transitioned into Melodie, for obvious reasons (even more musical!).

You feature female characters but please also tell us about your male protagonists Xavier and Jackdaw Hollow.

This is a really hard one! For my whole career, I’ve written girls. I’ve always been passionate about presenting and examining the experience of being a young girl, learning what that means in the world. However, as I’ve got older – and taught by my wise kid and her friends – my ideas around gender have transformed and become deeper and more nuanced. I don’t think I could have written “boy” characters with any confidence before the past few years (and it’s probably no coincidence that Xavier and Jackdaw both subvert typically “male” stereotypes). I’ve been so lucky to have so many young people in my life – through my kid – who don’t conform with the ideas I always had about what it means to be a boy. Xavier and Jackdaw definitely draw heavily on the kids my kid is friends with – smart, sensitive, complicated, deep-thinking kids. I’ve loved meeting Xavier and Jackdaw on the level of characters and humans, without feeling hamstrung by ideas about how people of their gender should behave. I hope both of those characters help young people to feel seen. Being a “boy” doesn’t mean anything you don’t want it to mean.

In The Calling of Jackdaw Hollow, Jack teaches Angeline to read. He wanted to teach her the beauty he saw when he read the perfect sentence. Could you quote one of your sentences from any of your books that is closest to perfection or that you are very happy with, and explain why?

That one I find impossible to answer. I don’t feel like anything I write is perfect and I’m not sure I want it to be. I’ve always thought that beauty lies in flaws. I know that there are flaws in my writing – sometimes it’s by design (probably a lot of the time it isn’t), but I think that imperfection is much more interesting than perfection. And yes, I have inexpertly dodged that question!

Melodie and Aster are from two different series but have interests in common. How are these girls similar?

I think both Melodie and Aster are desperate to be understood and desperate to be loved. They feel “outside” of the crowd and like the way they behave is not normal or worthy of love. I just wanted to wrap both of them in a hug and tell them it would all be okay. I hope, in the end, they both believe this.

Why are there missing mothers in Aster’s Good, Right Things and Xavier in the Meantime as well as in the Direleafe Hall books?

I often use writing as a way to untangle my own experiences and my own past, and to find ways forward from trauma. I’m also deeply interested in examining motherhood and the ways that different people experience it. The idea of the absent mother is one of the few remaining taboos in society and a role many people can’t understand. In both these books, I wanted to unpack what it might be like to be the mother who left, as well as what it feels like to be the child left behind.

Please tell us about one of your characters who longs to be ‘seen’.

The most obvious example, of course, is Melodie, but I feel like all the characters in these stories wish for it. Middle grade fiction is so much about finding out who we are and what our place is in the world. There’s a reason so many children’s books are written from the perspective of the “outsider”, outsiders see everything that’s going on but are, largely, unseen themselves. This gives them a unique perspective on society. If you combine this perspective with the innate human need to be acknowledged and understood, I think it makes for fascinating characters. And, of course, many writers were outsiders as children! Xavier is, for me, the most interesting of these outsider kids. He’s very flamboyant and theatrical on the outside, but is haunted by his own mind and so never really feels part of anything. This dichotomy was really interesting to me.

How have you used stars as symbols across these two series?

I’ve always been hooked on the idea that we all come from stardust – that we’re all, when it comes down to it, celestial beings. There’s something miraculous and magical about that. I think, for me, that serves as a metaphor in many of my books. We look at the stars when we’re dreaming, as some far-off, mystical place – some goal we’ll never achieve. But really, when we look at the stars, we’re looking at home. We’re all alien, all foreign, all trying to find where we belong. We all share that, as a species. But if our home is billions of miles away, how can we ever really reach it? Our real home lies in each other and the connections we make on earth and knowing we come from the same place helps us to find those connections.

Your writing is sensory. Please give an example of where you’ve used colour.

There’s this story in the writing world:

An English professor takes a class on the writing of a famous author. She instructs her students to examine the metaphorical use of the colour blue in the writings of the author. The famous author comes to visit the class and is asked about this. Her reply? “Oh, I never realised I did that. I guess I just like blue!” I know I use colour frequently in my books – as well as music. Maybe it has something to do with the fact I’m autistic. I’m very connected to the sensory world and colour and music both evoke strong feelings for me, and calm me when I’m anxious. I don’t think I’ve tried to do anything deeper than that but it’s always amazing to hear people’s interpretations!

When do you use realism and when is fantasy the better choice for your books?

I’m a very instinctive writer. I don’t do a lot of planning and I tend to just follow my heart. Sometimes that leads me more into fantasy and sometimes more into the realistic, but I think they’re both intertwined. My speculative fiction is very much grounded in the real and my realist work has a lot of magic about it. The characters and the story dictate whether the books leans more one way than the other and I love both equally.

How / why are these five children’s novels also for adults?

I’m a huge reader of children’s fiction and I think the best children’s books can be equally loved by adults. But I write for kids. I never really think about whether adults will like the books, too – it’s a bonus if they do!

“If anyone is ever unkind, appeal to their humanity. Appeal to the small spark within them that is still made of stardust. That’s the purest thing. We are stardust. That’s what being human means. If a person is unkind, it’s only that they’ve forgotten. To remind them, show them kindness yourself. Show them joy. If that doesn’t work, show them the stars.” (The Ballad of Melodie Rose)

Indigo in the Storm

(2023)

Kate Gordon, Riveted Press

Review in Magpies magazine by Joy Lawn (reproduced with permission)

Indigo was born in a storm. She learned to be quiet at home to avoid her erratic, neglectful mother’s ire. However, she never felt big or good enough. When her mother eventually abandoned her, Indigo raged to release her pain and to be ‘seen’, she hoped, even by her far-away parent. Now an exhausted twelve-year-old, she is taken in by Noni, Aster’s aunt. (Aster and Noni are characters from the award-winning Aster’s Good, Right Things.) Noni understands and comforts Indigo and tells her that in time she will find out why she was really her – what really set her soul alight!

Indigo recalls the many men her mother prioritised over her. She talks to bugs instead of people because they do not judge her. Even though medication and therapy ease her angst, she retreats to her dilapidated former home, a borrowed place. She loves living with kind Aster (who still suffers from anxiety and needs her hiding days) and spending time with neighbour Xavier (who features in the 2023 CBCA shortlisted Xavier in the Meantime) despite his invisible companion, the black dog.

New boy Liam is an Aboriginal environmentalist with ADHD, whose street art and graffiti slogans are making an impact in the community. Indigo feels an affinity with him and his ideas: Be the revolution… The eyes of all future generations are upon you.

An admirer of the painters Van Gogh and Seurat and a gifted artist herself, Indigo begins to turn her soul into words and paint it on the world. She embodies the Japanese technique of ‘kintsugi’, where cracks are repaired with gold. The new mortar is stronger than the former breaks. Indigo also has a refined sense of smell, which becomes vital to Aster and Xavier’s ongoing mission to save the sheep.

Kate Gordon’s writing is sensory and lyrical. Her imagery is potent and poetic. Indigo in the Storm is achingly insightful and leaves the reader with a metaphorical rainbow of beauty and light. Kate Gordon has undisputedly secured her position as one of Australia’s finest novelists for children.Joy Lawn