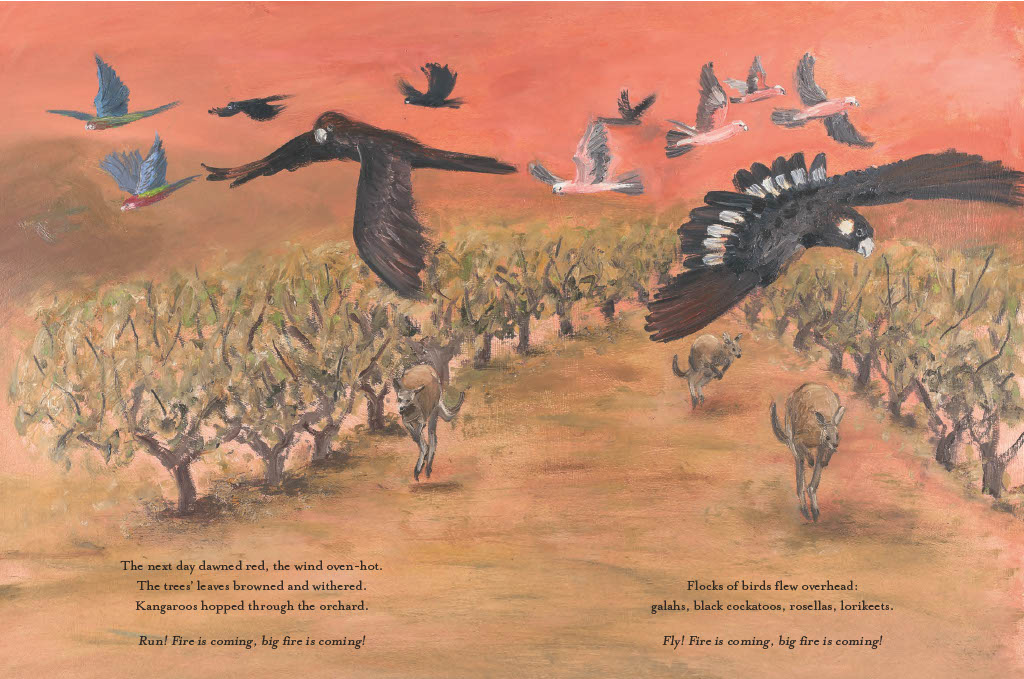

The Peach King: A contemporary fable about the resilience of nature written by Inga Simpson, illustrated by Tannya Harricks

Lothian Children’s Books, Hachette Australia

Interview with Inga Simpson & Tannya Harricks about The Peach King

“When Little Peach Tree was just a sapling, not much more than a stick bending in the breeze, all they could see was row upon row of other peach trees.

And, on top of the hill, watching over the orchard, branches tangled together like a crown – the Peach King.” (The Peach King)

Thank you for speaking about your powerful and glorious picture book, The Peach King with Paperbark Words, Inga and Tannya. It is both distinctly Australian and universal.

Inga

Inga, you share in your Author’s Note that The Peach King “began as a fairytale told by a grandfather to his grandchildren about a magical peach orchard” in your first novel Mr Wigg. I’ve avidly read, loved and learned from your books from Mr Wigg onwards. How prophetic that you wrote about a peach orchard over a decade before the events of NSW’s Black Summer of 2019-2020 and have now crafted this tale into another illuminating form. How, and why, have you made this story a fable?

Yes, it’s funny how things come around again. The original fairy tale in Mr Wigg, which was set in the 1970s, was quite traditional – and long! For the picture book I was trying for something more simple, one young peach tree through the seasons, but it lacked drama. Until I told my publisher at the time, Kate Stevens, the story about the Araluen peaches and the fires. She suggested working it into the narrative of The Peach King. (Why didn’t I think of that?!) As soon as I started writing, the story came to life. So I have Kate to thank – and for finding Tannya to illustrate the book. There is something satisfying about making the story more contemporary, while drawing on the feeling of its origins.

How is the peach tree a symbol?

I think peach trees do symbolise immortality, which fits. For me, the peach king and little peach tree stand in for all trees, any tree. There is something very accessible about orchard trees, as if they are almost part of the family. They live close to us and we are more conscious of their cycles through the seasons because we harvest their fruit. And the way we prune and tend to them, we do tend to notice their personalities. Mr Wigg came to being out of memories of my grandfather’s orchard and the abundance of summer.

How do you personify nature in the tale?

In all my stories I’m trying to shift the natural world to the centre and humans to the margins. So it is not so much that I’m trying to give the peach trees human characteristics, because that would be to presume that only humans have sentience, agency, emotions etc. In The Peach King, I’m trying to imagine what it might be like to be a peach tree, and to allow the reader to imagine, too.

The Peach King’s subtitle refers to the resilience of nature and you show this artfully in the book. Another subtle thread in the story is the communication of and between nature and trees. How do you perceive and show this?

We know a lot now about the way trees work with one another through fungal networks and so on. And that all ecosystems are interconnected. In my own observations of the natural world I find that birds and animals – and probably trees – are very much aware of each other and sometimes work together. Particular birds – New Holland Honeyeaters, where I live – take on the role of sounding the alarm if a goanna (or human) is approaching, for example. During the bushfires, many animals and birds fled ahead of the fire front, and I could feel and see the alarm being communicated. There were stories afterwards, of wombats sharing their burrows with snakes, echidnas and so on. The trees were the only ones not able to move, though they would have been aware of what was coming with the smell of burnt leaves on the wind and blackened leaves raining down. In The Peach King I tried to imagine what that might be like from their perspective.

Is it usual to have a king tree in an orchard like the Peach King tree that we meet in your picture book? If so, what is their role? Otherwise, what other roles may a tree play in a place or community?

Like a Mother Tree? I hadn’t thought of that. I think most commercial orchards are so manicured that it might be unusual, but in home orchards there is often one tree who just grows bigger than others, or produces sweeter fruit. A tree in a garden or park or playground can be a place to meet, to shelter, to picnic, to read a book under, or to retreat from the everyday world in calming, oxygen-rich company. They offer us so much more than fruit.

What is this story implying about leadership?

That one person, even a very small person, can make a difference. It takes bravery to speak up, but others will fall in around us. And in communities, we are much stronger.

Apart from those already mentioned, to what other themes or issues does the book allude?

In terms of leadership and making a difference, I’m thinking particularly of climate change, the loss of abundance and diversity, and the myriad threats facing our forests. We all know what we need to do – it’s a matter of doing it.

How does The Peach King epitomise your excellent body of nature writing?

Hopefully bringing trees to life for the reader and transporting them elsewhere for a time – with the help of Tannya’s beautiful illustrations.

Inga, your writing is beautiful. It is lyrical, sensory and poetic. What is an example that particularly pleases you?

Thank you. I had fun with the alliteration in the story: When the trees wake, their blossom will burst, their sap will sing, and their fruit will set – for another season.

How has Tannya extended your story or shown time passing in a way that perhaps surprised you?

Tannya’s introduction of the dog and puppy to help show the passing of the seasons was a delightful surprise, and the sense of the farm and family and neighbours around the orchard.

Which of Tannya’s illustrations captures the essence of The Peach King?

For me it is the illustration of Peach King on fire that is most alive, a little scary, and just as I imagined.

Tannya

Tannya, as in your other excellent picture books, your illustrations are painterly works of art in themselves. How would you describe your style?

I have mostly illustrated stories about the land, nature and animals. I think that the beauty of nature is in its imperfection and its constant state of flux. My style is loose and painterly to keep the illustrations expressive and active. They are impressions of time, place and weather that I hope drive the emotion of the visual storytelling and ignite imagination.

What media and process have you used for The Peach King? How have you created texture?

The illustrations are created with oil paint on large sheets of primed paper. Oil paint suits my process of working on multiple illustrations simultaneously, over a period of time. The paint stays alive during the process. I sketch the scene first in charcoal. The paint is then built up in layers, sometimes as a transparent wash and also as textured marks. I use brushes, a palette knife or my fingers to move the paint around. Then I draw back into the paint with pencil or charcoal to highlight detail and to pull it back together.

What has been your vision behind your creation of Little Peach Tree or the Peach King and the orchard?

I was lucky to have a generous amount of time to create the illustrations for The Peach King, so that the multiple themes and layers of the story could reveal themselves to me once I began interpreting the story visually. For me, Inga’s story suggests magical realism, where the reader can believe in real trees that ‘whisper warnings’ and “call up a cloud of birds”. I loved the opportunity to illustrate this beautiful, universal and dramatic story.

In the scene where little peach tree shows courage and leadership, and saves the orchard. Inga’s words in the final page of the story “their sap will sing”, gave me a clue. I was inspired by research by a bio acoustician who records the sounds of trees during periods of extreme weather such as drought. Pulsating sap creates a sound audible to birds and insects who flock to the tree. Nature provides the chorus.

How do you show cycles and generations in the book?

The story is as much about the legend of the Peach King as it is about the coming of age of Little Peach Tree. While the majestic Peach King fades, the Little Peach Tree is flourishing . Colour is a wonderful way to suggest the passing of time in picture books. In the peach king it is via seasonal change in the orchard, the weather and the land. I also found a way to weave a dog into the illustrations! To demonstrate the passage of time with a young pup whose growth mirrors the seasonal growth of little peach tree. The dog is also representative of generations of farming families.

What do you hope children take from this book?

I didn’t get to visit an art gallery until I was in high school and my mind was blown. Until then, picture books had served to feed my imagination and inspire me. Picture books are more accessible than art galleries and often the first encounter with art for a young reader. I hope that the paintings in The Peach King spark fresh curiosity, imagination and inspiration to readers with each reading. Just like my favourite paintings in the state gallery that reveal some new detail or meaning each time I look at them.

The Peach King at Hachette Australia

https://tannyaharricksillustration.com

********

OTHER RESOURCES

- Inga Simpson about The Book of Australian Trees Interview at Paperbark Words blog

- My review of Kookaburra by Claire Saxby & Tannya Harricks and mention of Dingo at Paperbark Words blog

- My review of Understory: A Life with Trees by Inga Simpson

I was fortunate to facilitate a session with Inga Simpson and Tony Birch at the Sydney Writers’ Festival in 2016 (see write-up below). I had been following their literary careers by reading their writing as it is published and have continued to be absorbed by their exemplary work.

Inga Simpson sees the world through trees and hopes to learn the ‘language of trees’. Understory: A Life with Trees (Hachette Australia) is nature writing in the form of a sensory memoir. It traces her life in ten acres of forest in the Sunshine Coast hinterland alone and with N and her two children.

The book is beautifully and aptly structured as parts of the forest. ‘Canopy’ includes chapters on the Cedar, Grey Gum, Rose Gum and Ironbark; ‘Middlestorey’ features Trunk, Limb, She-oak and Wattle; and ‘Understorey’ focuses on Sticks and leaves, Seedlings and Bunya, amongst other natural elements.

Inga Simpson lived in the forest for ten years. As ‘tree women’ and ‘word women’, she and N wanted a ‘writing life’. They referred to themselves as ‘entwives’, a term from Tolkien and named the writing retreat they established, ‘Olvar Wood’, from Tolkien’s The Simarillion. The retreat was an oasis for writers but, along with financial and other problems, its demise is foreshadowed throughout the memoir. We celebrate and agonise with the author through the refurbishment of her lovely cottage despite ongoing leaks and mould; the acceptance of her debut novel Mr Wigg, the completion of Nest and the winning of the prestigious Eric Rolls prize.

Readers are welcomed into the forest through the author’s words: ‘these small acts of tending … [tell her] story of this place’. Also memorable are the author‘s acts of tending the forest: clearing weeds, cutting timber and replanting. She recognises and absorbs ‘Indigenous concepts of country [which] include a responsibility to care for the land’.

Once her eye becomes attuned, she discovers flame tree seedlings and young cedars in an almost mystical way. She learns to take time to look for the ‘details and patterns and signs just waiting for my eye to become sufficiently attuned’. As part of this process the author develops ‘nature sight’, where living creatures such as sea turtles and sea eagles, reveal themselves to her.

Inga Simpson concedes that she may not have achieved her desire to become ‘fluent’ in ‘the language of the forest’ but she has become ‘literate’ and literate enough to share her knowledge and understanding through lyrical, unforgettable words.

- Inga Simpson and Tony Birch at Sydney Writers Festival 2016

My Write-Up

I was very fortunate to chair a session with Inga Simpson and Tony Birch at the 2016 Sydney Writers Festival.

They both have had books long or short listed for the prestigious Miles Franklin award. Tony’s Ghost River is currently longlisted.

It was also shortlisted for two categories in this year’s NSW Premier’s Awards: the Christina Stead prize for fiction and the newly created Indigenous Prize.

Tony and Inga both know their way around universities, as well as being accomplished fiction writers who take us on secret, sensory journeys with their young characters, particularly into natural ‘inbetween’ places, particularly around rivers and trees.

I was first aware of Inga’s writing when her debut novel, Mr Wigg was shortlisted for the Indies awards. I remember the ripples that her lyrical writing about an elderly man in his orchard caused in the literary community.

The writing in her second novel Nest is also the equivalent of fine slow-cooking with its depiction of Jen’s life in a sub-tropical forest but it is utterly captivating and suspenseful at the same time.

Her new novel Where the Trees Were also has evocative descriptions of place – the river and trees.

A group of boys and one girl, Jay, spend their summer holidays before starting high school in the bush, mainly around the river. They find a circle of trees that seem to be out of time and world. Designs are carved into their trunks. Are they a story or code?

The parts of the story about Jay as a girl are told in first person. We also meet her as an adult in Canberra, told in third person.

The indolence of quite an idyllic childhood, although charged with the urgency of adolescence, changes to a harder-edged anticipation and anxiety when a conservationist, (we’re not immediately told her name is Jayne) is involved in stealing a carved Indigenous artifact, an arborglyph, a Wiradjuri burial tree.

Tony Birch’s writing is assured, direct and unpretentious.

I was very moved by his novel Blood, particularly the strength of character and loving heart of his young part- Aboriginal protagonist, Jesse.

His most recent novel is Ghost River, set in the 1960s where the intersected lives of two adolescent boys and the dispossessed river men play out alongside the Yarra River.

Storytelling and the changes and roils of life are intrinsic to this novel, reflected in Tony’s own virtuosic story-telling style which moves from energy and adventure to trouble, pathos and weariness and back again like the river itself.

I wonder how much of his own boyhood Tony has drawn upon to create his lively characters Ren, and particularly Sonny.