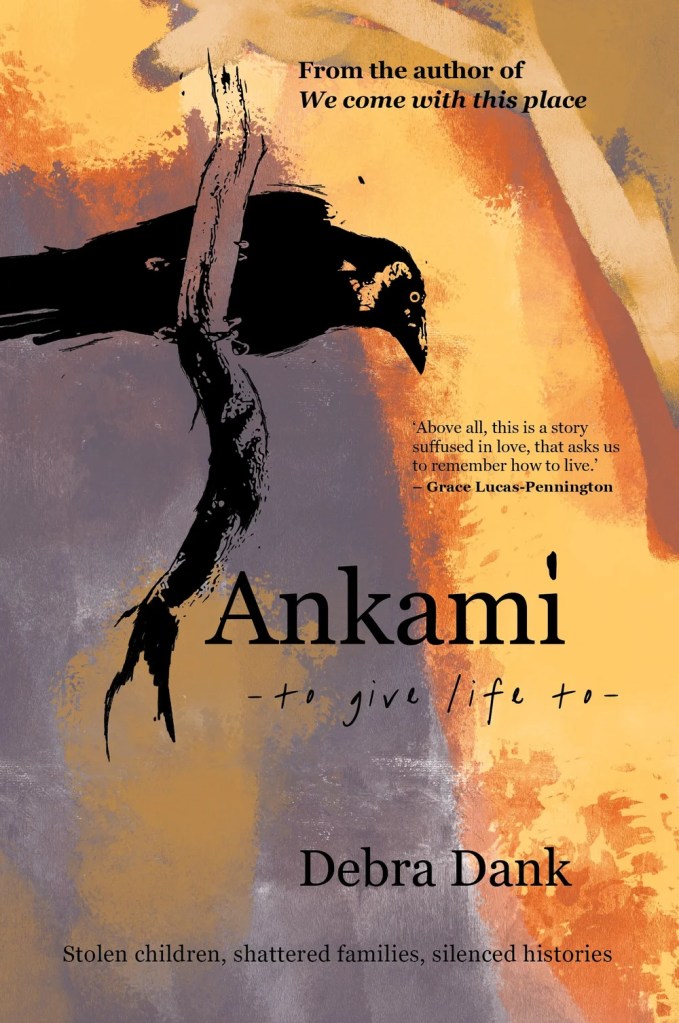

Ankami – to give life to – by Debra Dank

(Echo Publishing)

“So this is a story about time and words and ways because though many of the stories that lived here for thousands of years still wait to be told and freed to travel with the wind, other stories need attention now. These newer stories, which had their birth in recent times and are still looking for where they can live, urgently need the words and ears and hearts of us all, because we are all players in its living … and time is passing.”

(Ankami – to give life to by Debra Dank)

Author Interview: Dr Debra Dank

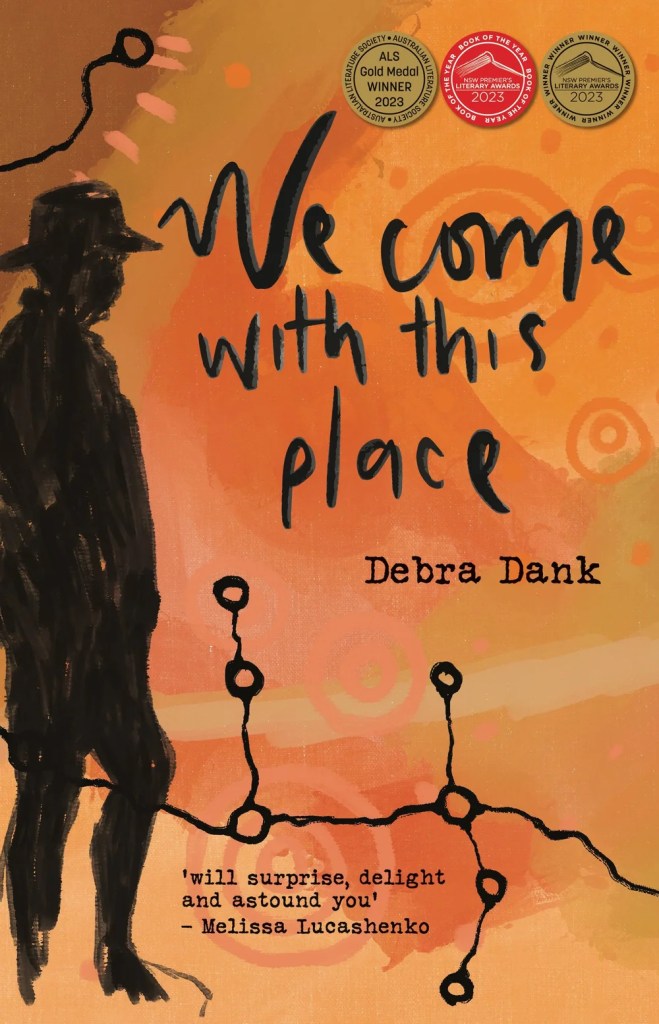

Debra Dank is a Gudanji /Wakaja and Kalkadoon woman from the Barkly Tableland in the Northern Territory. She is the literary peer of Alexis Wright. Her 2022 memoir We Come With This Place has won multiple prestigious awards.

Debra’s new book is Ankami, the searing yet enlightening story of her family: “stolen children, shattered families, silenced histories”. It is written with exquisite originality.

Thank you for speaking to Joy in Books at PaperbarkWords blog, Debra.

I can’t do justice to the profoundness and importance of this book in a few questions but have tried my best.

As revealed in your momentous new book Ankami, you are obviously an excellent writer, a deep thinker and are also rather mischievous. Could you describe yourself in three words?

Three words – introvert, not shy or passionate about words or curious by nature

You wrote Ankami after discovering the devastating, unconscionable truth about your family history. What style or structure have you used to write the book? For whom have you written it?

I always struggle with this type of question because I do not write with a particular genre or style in mind – I am possibly the most unintentional, intentional of writers and so it is fortunate that I imagine myself to be more of a storyteller and not so much a writer. The content of the narrative and what needs to be or is being said, drives and evolves the form the final product takes. I mostly, do not pay too much attention to any rules beyond good and proper grammar and punctuation but even then, I stretch and mould those rules if the narrative requires it. I think too that I follow the style of storytelling that I grew up with, grew up hearing and practicing. For me, this is why chapters and other breaks in prose frustrate me.

I have heard so many experts say that oral narrative cannot be written down, and I agree with that to a very small extent (voices literally cannot be written down) but the rhythms that I heard as a child are still, I hope, there in my telling because it cannot be any other way. I am a product of my upbringing, and all those early teachings were strong and valid and good, so they stay with me, and I work to ensure they are not lost in this fast and ever-changing world. I believe that things are lost when we work to conform… when we work really hard to write down tales and narratives that follow scripts and recipes.

Those conventions of written prose were developed to help develop particular skills and knowledges of specific written forms, but I do not believe that we must stay within the boundaries to such an extent that we lose the nuances or fail to create a literary atmosphere around what it is we want to tell. That is not to say that I am a resolute and committed breaker of rules and conventions of expression of the English language, but I will absolutely leave them behind if they hinder what must be said.

As for why and for whom I write the telling, it is for my reader whoever they may be, but I hope my readers understand that I am honouring them by not squeezing myself into a genre-specific form or a language which is not mine or philosophic ethos, that is also, not mine. As a Gudanji/Wakaja person, I claim and tell-write through and with the same privilege as mainstream writers do – with my community’s values and ways of knowing and being, my world, at the centre. Mostly, I write for my family…

How does the book’s cover represent something of its content?

For Gudanji, and many other Aboriginal groups that I do not speak for, the crow brings stories and knowledge in different ways.

The stories are often those that are uncomfortable, harsh and difficult to hear, the crow also by its very presence, reminds you of your humanness and the obligations you have to others including your non-human kin but also call you to be present in the world and be ready to be response-active (I often create words where there is nothing in English to express what I mean – I created ‘ response-activity’ as a singular word to identify the active next step to responsibility which is merely your ability to respond without that absolute manifestation/expectation/demand of action).

The image of the crow on this cover is reworked from a photograph we took when we were all up home on Country, so this one really is the Gudanji ‘harbinger’ not so much of doom, but of difficult and harsh stories.

The colours were chosen to represent Gudanji/Wakaja and Kalkadoon Country. I was born in love with red earth and will not ever, not love the colours of my place including its shades and shadows. My daughter Ryhia designs [Nardurna} my covers and that makes these books extra special.

Why have you alluded to the nursery rhyme Baa, Baa, Black Sheep in Ankami?

I allude to this nursery rhyme for its appropriateness and relevancy. Some of the themes that BBBS allude to include slavery – the word ‘Master’ is also there and like all words utilised within storytelling, is deeply nuanced.

The term itself, ‘black sheep’ , is so widely used, we can all relate to it in one form or another, but we don’t always consider the multiplicity of connotations in its use. The most obvious, of course, is that old telling of the black sheep in the family – so relevant of many Australian families – black and white.

Sheep as a group, poor things, have an awful reputation as being somewhat slow and unintelligent—an unthinking herd animal. Thus, the idea of this type of sheep-person, alludes to someone following others which subsequently produces a crowd. In this context, many of the ‘crowd’ do not do their due diligence around the erroneous narratives about Aboriginal people. It also tells us something of a ‘lazy’ citizen who does not participate rather passively follows and therefore adds an inauthentic weight to a seeming dominant narrative. This, of course, does not reflect a truly informed participation. An example is the breadth of people who believe the 26th of January has ‘always’, since the arrival of Arthur Phillip, been Australia Day and they are not cognisant of the very recent development leading to such claiming. Another reiteration is the volume of people who imagine something intrinsic to being Australian will be lost if the date is changed or if we, as a nation, become better informed and accepting of the range of positions this specific date brings about.

The earlier comment of relating black sheep to slavery is an important viewpoint employed here. Slaves do not have the ability to make their own decisions and life journeys so the ‘following’ as if unthinking, is also useful here in a metaphoric deception because, of course, the imagination, as with future manifestations, is something else and can be a vehicle for far reaching fancy and or resourcefulness.

On page 93 you write piercingly, “those words invaded and claimed residency …’” . What do you mean by this?

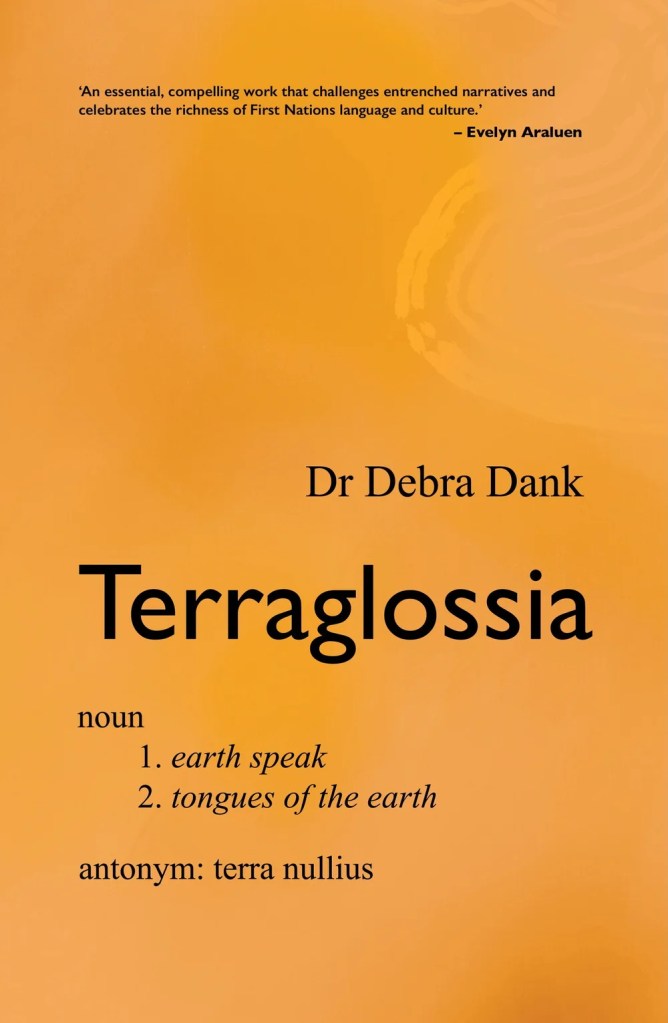

The English language arrived here with those first arrivals, with the boats that came from literally, the other side of the world. English language vocabulary, names, identifies and describes contexts, concepts, situations and ideas that exist in and of the English-speaking world. English, a wonderful language, grew for, with, about, and by the English-speaking community. Our acceptance that the English language is enough to articulate cultural contexts beyond the English-speaking world is troubling and has far reaching consequences. There are as many different languages in the world as there are cultures because of the differences that exist between cultures – difference not deficiency. If one set of vocabulary was enough to speak the multiplicity of truths that exist in a multicultural world, there would be no multiplicity or diversity at the levels there are. English may be adequate to identify the big concepts within the human condition, but it cannot identify the fullest scope, nor the critical details of how such concepts are evident within different communities. We must understand that translation alone responds to one need – that of an immediacy in understanding, however, extending vocabulary sets allows us to become better and more informed of human diversity and it ensures we become more inclusive. This is in no way a rejection of the English language, but we must stop imagining that it can be inclusive without us all doing a lot of work to make it so. An attempt and illustration of this is the earlier mentioned term, ‘terraglossia ’, a term I created to describe a widely held belief within Aboriginal communities, that the wider world and our non-human kin all have voices which we should heed.

Terraglossia [Dank, 2025] is also the title of my second book.

Could you briefly tell us something about ‘invisibility’, ‘imaginings’, ‘illusions’ and/or ‘memories’ from your book?

Aristotle has been credited with a quote which I like, and it says, “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” I think, in this multicultural world, it is the mark of deeply human thinking to entertain a thought without accepting it for the self, but which is accepted as a possible truth for someone else.

Your question of invisibility, imaginings, illusions and/or memories, highlight, for me, these concepts as possible ‘truths for someone else’ beyond the English framing. For example, the idea of memory exists in slightly different and broader ways for Gudanji – in my first book We Come with this Place (2022), I told a story about my then five-year- old son talking about his feet having grown on Gudanji Country and having experienced life with previous generations. He understood that he was borrowing his feet, that they [his feet] had walked our place many times throughout the past before they walked with him. This type of knowing is a deeply Gudanji one and is not in any way ephemeral rather the understanding now being explored in Western science as cellular memory.

So, this is an important question because it identifies several of the cultural traits/practices that are different between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people that I have alluded to in the response above.

Notions of memory, invisibility, imagination and illusion are all understood from within a culturally defined space and for people who speak English as a second, third or fourth language, much is lost in translation and the lack of vocabulary that expresses such culturally different understandings.

How have you balanced or alleviated writing the darkness of much of the content with light?

This is another question that I find complex but not in the way that I believe you mean with its asking.

If people are aware of the Closing the Gap statistics, they will understand there is so much perceived darkness in the everyday human condition of Aboriginal Australians. Most weeks, many Aboriginal families deal with death and loss or the impacts of racism or attempts to diminish our humanity or some other event which causes that darkness, as understood by Aboriginal people.

Many Aboriginal friends and colleagues talk about being in a constant state of mourning and live with on-going, incomplete Sorry Business. Many of us have long learned to balance that darkness and have become a little more adept at balance but it still hurts so the little things are truly celebrated. A smile or a hello, a hug, the touch of a hand, the depth of colour in a new leaf, the sighting of a bird as its call comes to you and lungs full of the freshest air are all beautiful and impactful moments that, if we be in that present, help to balance. One of the biggest ways of balance is knowing that we all die – no-one is escaping and that is the natural order of things—reality. I think it is important to have clarity of what constitutes grief and what constitutes celebration for life and to filter that binary through choosing to indulge in moments of joyful living.

Last week, there was a break in the rain in the community where many of my family live, so four funerals were held on that one day. There was up to 10 metres of water running through the river, so everyone knew timeliness was critical. On that one day there would have been many intense and quiet moments of reflection and memories being pulled into the present, soft voices speaking with what some consider imagined presences and a lot of time with family observing the rituals that are held close.

Those small things favourably hold up the light against the darkness. Gudanji were stoics and practiced pragmaticism long before Seneca, Aurelius or C. S. Peirce.

Could you please tell us one thing “polite Australians” (a term you use in the book) must know?

Oh goodness, we must ALL know this place was invaded and stolen and it will always be land that was invaded and stolen, in the most awful way, from Aboriginal peoples. Part of that knowing is that that knowledge should NOT be accompanied by guilt rather a gratitude for what we have and a willingness to not take it for granted, to nurture Country and be good guests within this amazing landscape. This means honouring Country and knowing that we are all inextricably entangled and if we abuse Country, as we are guilty of doing in our chase for the next bright and shiny thing, we are ultimately abusing ourselves.

How do you feel now you have finished writing the book and it’s out in the world? Relief, sorrow, anticipation, hope, or something else?

I am looking for the next story to tell – I think I have found it – in fact, I know I have found it, so I am feeling excited thinking about the challenge that I am creating for myself with the new book. I am also at a very interesting crossroads because I have had my three contracted books published by Echo and am now officially without a publisher so, yes, anticipation is a good word here.

My journey to try to find the missing family will be slow and I know will have many roadblocks that I have little control over, but I will continue that path. I remain grateful to have found that they exist and that is a joyful thing, I will always be sad that they are missing and know I may never find them, but I have several good leads now that I understand what those beautiful women were trying to tell me and what my dad was doing. Sometimes, that balance you asked about earlier comes from knowing what can and what cannot be and accepting that some things cannot change despite all the wishing and hoping.

How does ‘Ankami’, the title of your book suggest some sort of way, truth or healing to move into the future?

I think there are several ways this title suggests some type of means, truth or healing, that may assist us to move into the future.

Firstly, way , Ankami (to give life to) comes from a non-English, profoundly Australian language. My language, like all Aboriginal languages, grew and evolved here over thousands of years, not in a recent nomadic arrival. It still amazes me in the most challenging of ways that Aboriginal languages are not recognised either nationally or internationally as the oldest continuously practiced methods of communication in the literal world. How can that be? Why are non-Aboriginal Australians comfortable with and participate in this more-than-erroneous lie? Aboriginal languages, having grown here, give so much knowledge and information about this country that is desperately needed now.

Secondly, truth , to give life to, as has been suggested, is about truth telling but I like the different words that are spoken with different accents – Ankami, anchor me or anger me – they all might have something to give readers.

Thirdly, healing , too many times, the difficult contemporary situation of Aboriginal people is positioned as an ‘Aboriginal problem’. The truth is significantly more complex than that. Any issues are Australian issues because the arrival of the English-speaking community was the catalyst for such contemporary issues. We, all Australians, now benefit from Aboriginal people being displaced, so it is a national concern and a national responsibility needing response-activity even if it is accepting that Aboriginal peoples are the first Australians.

Aboriginal peoples are the first Australians.

Thank you for gracing us with your wisdom and pain, Debra. Your generous responses have fulfilled your desire to “fill some of the spaces that may need more noise but also … add flesh and scope to this conversation.”

Sincere thanks.