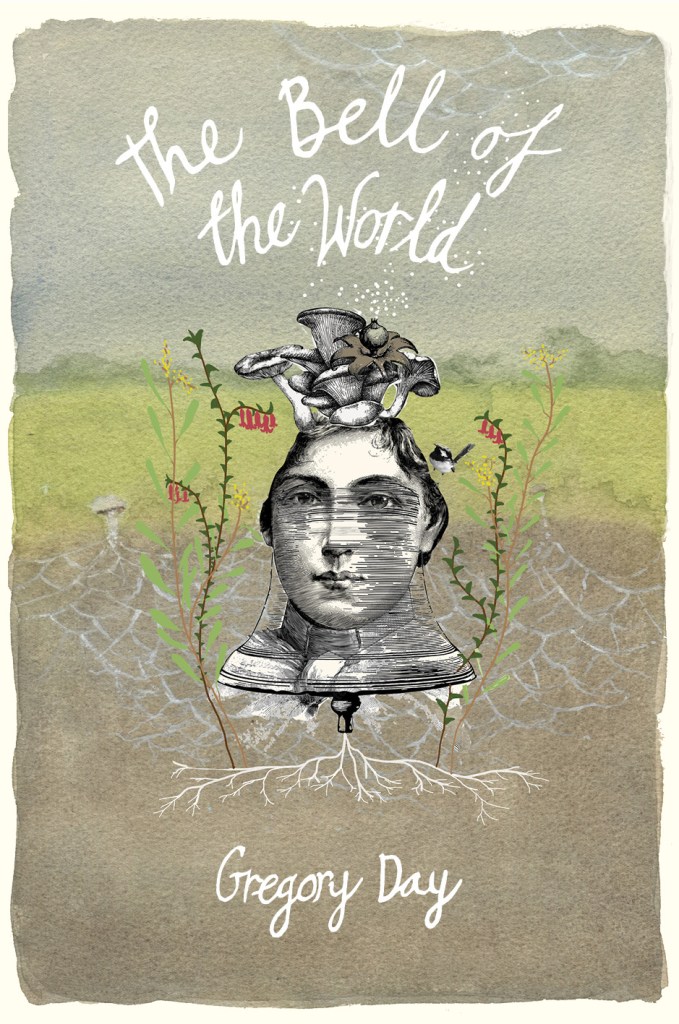

The Bell of the World

by Gregory Day

Author Interview at PaperbarkWords

“The world is a bell that sometimes only rings after long intervals: indeed it is often in the intervals where the suffering, and therefore the wisdom, lies.” (The Bell of the World)

Gregory Day is the awarded author of The Patron Saint of Eels, Archipelago of Souls, A Sand Archive and other well-regarded novels.

The Bell of the World (2023) largely inhabits a seemingly archetypal Australian landscape where the bush meets the sea. In (and outside) that space Gregory Day masterfully creates scenes, impressions and augmentations that awaken or jolt the reader’s senses. Dislocations become interconnected.

The Bell of the World abrades and illuminates. It makes you feel. It makes you question. It makes you seek.

The Bell of the World is shortlisted for the 2024 Miles Franklin Book award alongside:

Praiseworthy by Alexis Wright (Giramondo Publishing)

Only Sound Remains by Hossein Asgari (Puncher & Wattmann)

Wall by Jen Craig (Puncher & Wattmann)

Anam by André Dao (Hamish Hamilton, Penguin Random House)

The Bell of the World by Gregory Day (Transit Lounge)

Hospital by Sanya Rushdi (Giramondo Publishing)

The Bell of the World is published by Transit Lounge.

******

Thank you for speaking to ‘Joy in Books’ at PaperbarkWords, Gregory.

Congratulations on The Bell of the World being shortlisted for the 2024 Miles Franklin Award.

I’ve been longing to re-visit The Bell of the World after reading it last year and greatly appreciate your insights here.

I think that The Bell of the World is the long-awaited successor to Peter Carey’s Oscar & Lucinda, a novel that, although I read it many years ago when first published, has left potent images that stir my imagination. I think that both The Bell of the World and Oscar & Lucinda leave indelible symbolic images.

You may or may not be happy with this comparison because you have, of course, created something unique and you deeply explore different themes.

The title The Bell of the World and the idea of the ‘bell’ suggest many possible ideas.

“‘The thing is, uncle, a bell focalises an illusion. The oneness of the world when actually it’s teeming.’” (The Bell of the World)

What does the bell signify to you?

Firstly Joy, I have to admit that I’ve never read Oscar & Lucinda. I was a big fan of Illywhacker when it came out back in the 80s and still vividly remember the brilliant tragi-comic scenario where Charles Badgery is hoping to get his motorbike fixed by the depressive genius in the Mallee. What a vignette that is. Occasionally I drive the 50 odd kilometres from my home across to the Inverleigh pub for lunch (my ancestors are buried in the cemetery there) and was amused to discover that the pub had recently restyled itself as the Illywhacker pub. Apart from anything else it was good to see a modern Australian novel getting a nod in such a mainstream setting. That’s becoming increasingly rare in these post-literary times. I suppose now I’ll have to go back and read Oscar & Lucinda on your recommendation.

As for the bell in my novel, well, I’m reluctant to reduce the layers of symbolism in the novel to neat paraphrases, but I suppose I could say that in the novel the bell represents monoculture, with all its constrictions of, and presumptions about, what is already flourishing in the landscape.

Sarah’s ‘altered’ or ‘augmented’ piano is a highlight of the novel and, for me, its most enduring image.

I found myself gathering things as I walked, then raising the grand piano lid and placing first sticks then bones between the strings, affixing fern-fronds too on the hammers that hit them, leaning over the keyboard as I depressed the notes to see the new hybrid thickness of felt advancing, and shards of worn old fence-wire loops between them. A kangaroo bone prevented one hammer from doing its work … (The Bell of the World)

Sarah later adds twelve she-oak needles, a banksia leaf, a roo-rib and a pyramid of stuffed cockatoos. The piano becomes a “bush-machine”, a “new instrument”, a “prepared piano”.

Could you tell us what the altered piano means to you?

I am interested in the natural inventiveness of remote societies, communities that live on the margins of the central organs of power where behaviours are typically more standardised. One of my favourite writers is the Icelandic Nobel Prize winner, Halldor Laxness, whose novels depict many different kinds of community improvisation in historical and modern Iceland. His books are very funny, and so magical and strange, but they are very much seeded in the reality of his remote homeland. I’ve had some experience of this kind of thing here in Australia and I do love the way people outside the big city-grids do things their own way and with whatever materials are at hand. As a musician I’ve been aware of John Cage’s experiments with the prepared piano for a long time. Cage lifted the lid of the piano and placed extraneous objects inside the instrument to create a variety of new sounds when the hammers hit the strings. He did this of course within the largely urban artistic milieu of American modernism in the first half of the 20th century and became very famous for it.

I think that my imagination is often fired by juxtapositions of seemingly unrelated materials which are actually harmonious at a deeper unsuspected level, so it seemed perfectly natural to me that on a remote Victorian farm in the early twentieth century an inspired young poet-musician would come upon this prepared piano idea all by herself, and long before it had ever occurred to John Cage, Henry Cowell, or any of the other modernist experimentalists. For Sarah there is a deeply personal imperative to all this. It is a way of adapting a European instrument – the piano – to better express the landscape she is in and of. In doing so she finds her way into a more personal sound, precisely because it reflects the environment around her. It also expresses the hybrid state of her being as a European Australian.

How is Ferny and Sarah’s homestead (and their life there) a part of and also a contrast to its natural setting?

I think the novel charts how Sarah and Ferny become reflections of the hybrid nature of the place. Ferny’s temperament is that of an unabashed lover of life, he is something of an experimentalist himself, both as a farmer, in his personal life, and in his embrace of the artistic avant garde during his overseas travels. He has an enthusiastically eclectic mind and thus is keen to cultivate Sarah’s talent for expressing her absorption and immersion in the natural world via music and poetry. Ferny’s natural openness also gives him a clear view of the central transgression against First Peoples that has taken place in the colonial Australian situation he has inherited. It is in the nature of the specific character of Ferny’s self belief then, in part afforded him due to his privilege, that he is a happy soul who is open to truth, and sometimes despairing about it. So the homestead becomes a place that is fluid, changing, emerging, letting the outside in rather than shutting it out. This culminates in the farmhand Joe’s movements in the final scene of the book. Ferny and Sarah are in thrall to the world they are situated in, rather than living in opposition to it.

How does Sarah, your protagonist, flower?

When Sarah is at boarding school on the coast of Devon in England she becomes aware of how the landscape of Australia, the country of her birth, has become synonymous with her inner self. She senses an enormous living expanse within her self, a psychogeography of sorts, she sees it in her mind-eye and she feels this inner landscape as a space full of energy and potential that the low skies and hyperformalities of England only seem to want to squash in her. So when she is sent home to her Uncle Ferny’s farm she actually is returned into that landscape she has been carrying around inside her all the while. It is difficult for her at first to get her by now damaged psyche and personality to marry with the teeming bush around her, but with her caretaker Maisie’s strength and kindness she manages to. And it is then that she comes fully into herself, her divided selves are united, and her interior world becomes harmonious with the landscape around her. Something has to come of her new awakened energies and so, with Ferny’s encouragement, she celebrates this marriage through her music and writing.

Music is integral to the story. It is particularly found in nature, often through birdsong. Could you give an example of one of your images of which you are particularly pleased and explain why?

Integral to the novel for me is the way the sound of the ocean suffuses everything that takes place there. It is the ultimate soundtrack. Or to put it another way, it is the musical key in which this symphony of place is set. Sarah’s sensitivity to it is a clue to her character. To ring a monocultural bell in the landscape seems entirely tautological to her, or worse. A bit like putting an unnecessary fishing jetty on a riverbank, Just as the riverbank is already there to fish from, the bell of the world is already ringing. It is the imperative of the novel that we need to be tuning into it.

What is the significance of “interleaving” and “interstitching” in the novel?

Sarah’s piano is a version of this interleaving but I suppose the key motif of it in the book is the physical stitching together of two magnificent novels, Joseph Furphy’s Such Is Life and Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. This is done by a curious bookbinder, living alone in a kind of Dickensian marshland outside Geelong, to whom Ferny takes his beloved and battered copy of Such Is Life to have it rebound. Well, he gets more than he bargains for because when he returns he finds the bookbinder, an early lover of Moby Dick before the book was famous and something of a frustrated writer, has had a vision of the two novels – one American, of whalers and the sea, one Australian, of bullockies and the land – being bound together to form some kind of ultimate book of the world. In his eccentric wetland solitude the bookbinder has applied his skills to this task so that when Ferny and Sarah return to pick up the mended book they are shocked to find another thing altogether, a much larger hybrid book. Sarah’s altered piano and the bookbinder’s hybrid book are examples of how fiction can embody ideas visually, through objects, and magically real collisions. A novel is not an essay – at least not in my hands – but I suppose these motifs talk about the real life-world of the biota we live in, where everything is deeply connected whether we initially realise it or not. In the modern era such wild cultural convergences are a staple of everyday life, they can be seen everywhere, in city and country. All you have to think about is the diversity of the food we eat these days. One day bangers and mash, the next day laksa. I think these now normalised combinations are the fruits of an underlying cultural mycelium that proves the connectnedness and commonality of all things – if only we are prepared to see it that way.

What is the importance of time and space in the novel?

I think in some key respects this is a novel about real time. The time that is a wheel not a straight line, an opening not a constraint. Time as music not just an elapsing thing. This is time that travels across the sky, time that advances and retreats from the shore, the time of adventure and return, rather than the false time of unending linear progress and profit. That is a fantasy unhinged from the realities of the earth. So yes, time in the novel is the real time of our animal-bodies, the time that the illusions of contemporary life have abstracted us from. The Bell Of The World is also a book in which polytemporality plays a major role. Literally speaking the book is set in 1910 and 1959 but actually it is set both then and now, not literally, no, but symbolically. It’s been said before that the past is never over, it is not even past. This is definitely the case in the modern nation of Australia which, despite the tireless work of so many, has still not managed to do the decent thing by the original and ongoing custodians of this land, at even a constitutional level. So we are all living the past every day and I think we live in the future every day as well. It is the future we are making after all. Sarah certainly experiences time in that way and speaks of it in the book. It is a key part of her transcendent aspects, why she is the character she is.

How would you describe your writing style in The Bell of the World?

Well, each novel of mine is set up for the style to somehow marry with the content. That’s my intention anyway, even if it’s an intention that is impossible to completely fulfill. The writers I admire most are those that achieve that aim, if only for moments. James Joyce. Dante. Emily Dickinson, Georges Perec. So anyway, I love both the conceptual and the artisanal side of the writing craft, and I love the variety and plasticity of the novel’s potential forms. What an art form it is! Prior to The Bell Of The World I have published a short spare fable about eels, a family saga about community and real estate, a comic surrealist novel set in a hotel, a historical war novel, a novel of ideas about sand. All these books have various approaches to style, to expansion and restraint, to the artisanal challenges of the sentence. And The Bell Of The World is different again. In some respects the book is an investigation of the Romantic impulse in a colonial context, so it does have something of an aesthetic lineage there. But the cadence and syntax of the sentences here are deliberately musical, which is entirely determined by Sarah’s character. I suppose my broader hope for the style is that it feels unclipped and a little wild, but underpinned by a deeper rhythmical and structural logic, which is just how we want, and need, the planet to be. In this sense I wanted the novel to teem like the landscape it is set in. I think of this way of writing as biomodernism. Is that too pretentious to admit? So be it. To embrace life and language rather than to wage a war on it. So yes, let’s call the style unpasteurised!

What do you believe is your finest achievement in the novel?

I dunno if anything about it is that fine, Joy. When a book is done you tend only to see the things about it that could have been better, but eventually you just have to move on. I suppose I could say that I’m happy to have sung this story in my own way. I opened the portals and allowed Sarah’s music to come through, not in any self-indulgent sense, but in a writerly way, as a craftsperson. My hope is that this approach might help readers to think again about where they live, to feel and open their senses to it, in order to foster all kinds of necessary reconnections.

Thank you for your deep, far-reaching responses, expressed so eloquently, Gregory. You’ve given us even more to ponder and discover.

All the very best with The Bell of the World and your other endeavours.

This interview deserves to be published as an addendum to the novel itself. Both are thrilling treasures. I am so pleased paperbarkwords gave rise to the conversation.

LikeLike

Thank you Carmel. Gregory has been very generous and insightful with his responses. They are a work of art like the novel itself.

LikeLike