Ningaloo: Australia’s Wild Wonder

written by Tim Winton

illustrated by Cindy Lane

Fremantle Press

Interview with Tim Winton about Ningaloo

“For those who come after”

(Ningaloo: Australia’s Wild Wonder)

Thank you for speaking about Ningaloo, your clear and powerful non-fiction picture book, with Paperbark Words, Tim.

Your book’s subtitle is Australia’s Wild Wonder, and you describe Ningaloo as “one of the last great wild places on the planet”. What elevates Ningaloo into this wild, wonderful group?

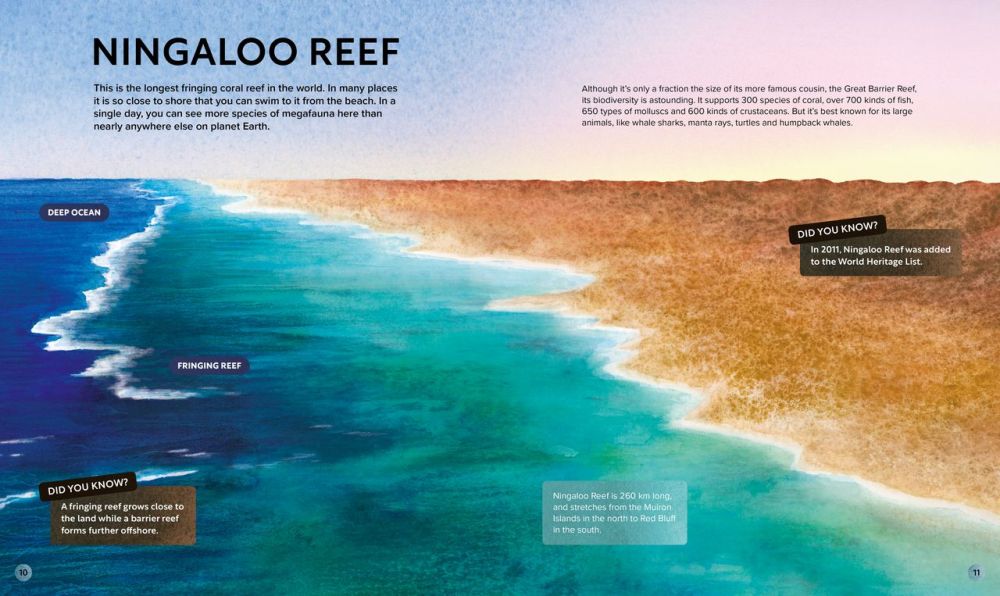

Ningaloo is distinguished by its exceptional biodiversity. Oceanographer Callum Roberts speaks about “the twin pillars of biodiversity” – variety and abundance, and Ningaloo is one place where you can see those with your own eyes. It’s always been exceptional because it’s the closest part of Australia to the deep ocean – the continental shelf is narrow, and so all these oceanic creatures aggregate in sight of land. This is why, in a single day, you can see more species of charismatic megafauna here than almost anywhere else on Earth. The other significant reason for its exceptional status is that the place is still intact. The reasons for that are not an accident.

What, to you, is sacred about Ningaloo/Nyinggulu or what makes it a place of wonder?

It’s special to me because it’s one place in Australia (and indeed, the world) where modern industrial humans have been humbled by wonder to the degree that they changed their attitudes and expectations to meet it. This part of the world was one just another bit of northern Australia to be exploited. The Cape Range, Ningaloo Reef and Exmouth Gulf were seen as oilfields (and were drilled at one point or another). The was a commercial turtle fishery that pushed green turtles to the brink of local extinction. Likewise, the whale fishery. The turtle hunt didn’t stop until 1978. The whale business collapsed before that. But right into the 90s and later, Ningaloo was still marked as an oil and gas tenement, and the Cape Range was viewed as a limestone quarry.

Within a single human generation, we turned 180 degrees in terms of how we saw the place. We saved it from ourselves and returned it to itself by agreeing to preserve it and celebrate it. It might seem odd to see this aspect as sacred, but I think it’s one of the most remarkable turnarounds in Australian history. And given what we all face globally, with an extinction crisis and the climate emergency, this is a phenomenon we should pay attention to and draw lessons from.

Ningaloo is a field of wonders, and I’ve been making that case for decades, but perhaps the biggest wonder of all is that we pulled back from the brink and saw it for what it was and then made the hard choices to protect it and to educate ourselves about it. Ningaloo is a place where we got it (more or less) right. That didn’t come from the top. This was the work of ordinary people. And that’s why Ningaloo remains a beacon of hope for me. (Tim Winton)

Whale sharks are well-known megafauna of Ningaloo. What is another creature that you find particularly fascinating? Why?

Well, there are so many creatures to choose from. I love swimming with manta rays. They’re smart, curious and sociable. They have the biggest brain of any fish, and they’re so graceful. I have a special love for dugongs, too. They’re shy, almost cryptic. I once had the opportunity to hold one in my arms (with four other people because they’re so strong) while we took DNA and attached a satellite tag. It was a pretty rare opportunity to hold 450 kg of animal and be eye to eye with it. They have terrible breath – a diet of seagrass!

I have learned from your book that Ningaloo is not only the reef. It has three ecosystems: Ningaloo Reef, Cape Range and Exmouth Gulf. Within these ecosystems, there are six communities. These include the coral reef community, the intertidal community, the seagrass community and the karst community. Which community is flourishing? Which is most at risk?

For reasons of space, we couldn’t fit the sponge garden communities, or the turbid coral communities, which is a shame. Until quite recently, all the communities were doing very well. But sadly, they’re all (even the subterranean karst system) at risk from climate change. This year we had a global marine heatwave. That brought a huge plume of hot water down from the tropics which stayed all year. Large portions of Ningaloo’s corals and seagrasses were damaged or killed. This is an event without precedent in this part of the world. (The data on this event were only finalised and made public after our book went to the printers.)

One of the communities is the intertidal community, where “sea and land connect and overlap”. Children would perhaps be most familiar with this space from their personal experience of beach holidays. It evokes the words ‘interstitial’ and ‘interstices’ – openings, cracks, clefts, crevices, fissures … spaces that interest children. How do they spark your imagination?

Well, my mind lives on the edges and in the gaps. I’ve made my living from liminal spaces for over 40 years. Kids have an instinctive passion for holes, tunnels, caves, gaps. We want to see what’s at the end of the tunnel, what’s around the bend of the canyon floor. But we’re also arrested by the meetings of things, the way things (and processes crash against each other), where one thing turns into another. Just as I’m fascinated by the space where the desert meets the sea, I’m interested in the space in which we change our mind or experience a change of heart. There’s a moment, or a period, or a space in which certainty won’t hold. I guess I see that as potential becoming manifest. This is the creative moment. In this way, we mirror nature, or at least show how we are claimed by it.

The Ningaloo ecosystems are varied. Cape Range has a “secret underground world of caves and waterways”, and Ningaloo Reef features vibrant, colourful coral gardens. If writing a children’s fiction book, which Ningaloo ecosystem might you set it in? Why?

I might choose the underworld. Just because it’s so peculiar, and I’ve never done it before. Having been down there, I can say it’s like nowhere else you can imagine – every creature is blind and feeling its way in the utter dark. It’s a zombie world of eyeless spiders, scorpions, fish.

I love that Cindy Lane has created her illustrations with a combination of seawaters, watercolours and other media. Which picture best conjures ‘seawater’ or the ocean for you? Why?

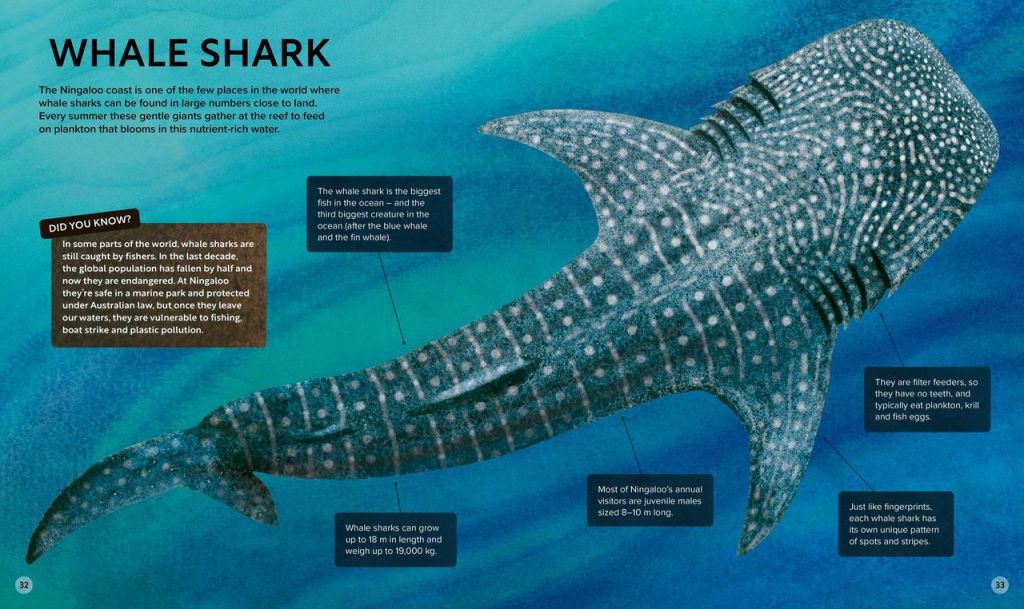

Probably the two-page spread of the whale shark. The animal contains all the colours of the water in its markings. The deepest water is purple tipping into indigo. You get that around 50-100 metres. Pretty wild to swim in that depth. It’s like swimming in your dreams. Without an animal to look at, there’s no perspective – it’s almost hallucinatory after a while. As you get shallower, you run up through the blues to aqua, but there are always bars and spangles of light, so there’s a lot of white to contend with. I guess what I’m saying is that the ocean is a mosaic of colours and temperatures, and that illustration helps capture it beautifully.

Since 2011, Ningaloo Reef and Cape Range have been national parks protected by the World Heritage List. What was your role in this? Which species have been most positively impacted by the protection?

I guess I was a part of the public education process and advocacy process that enable this to happen. Without halting destructive coastal development (2000-3, without the extension of the marine park (2005), and without a national government explicitly committed to the preservation of the estate, UNESCO would not have supported the listing. The campaign I was a part of (and for which people give me too much personal credit, I must add) made it politically possible for World Heritage to be achieved. Being a part of that was a kind of education for me. It had a big impact.

However, although Exmouth Gulf is a nursery for vulnerable species such as dugongs and sawfish, it is not fully protected. Why not?

There was a backlash to World Heritage from those who wanted to exploit Ningaloo’s resources. They wanted the Gulf to be a deepwater port for oil and gas, limestone mining, salt exports. And there was still an oil tenement in the Gulf. So they lost the battle over the Reef and the Range, but they got their way with the Gulf. Ningaloo’s defenders have spent the intervening years trying to fix that mess. We’ve killed off two salt operations in the Gulf’s pristine wetlands. Also a gas pipeline facility. Happily, this year the WA government committed to making the entirety of Exmouth Gulf a marine park with 30% sanctuary protection. But we’re still battling a proposed deep water port that’ll be smack bang in the middle of the whale refuge, so there’s plenty to fight for yet.

You include a section on how to learn more and take action at the end of the book. What is one thing that young readers could do to help Ningaloo?

Follow Protect Ningaloo. By following the community group Protect Ningaloo, they can help save Ningaloo’s whales from the noise and pollution of a deepwater port. If you follow on Facebook or Instagram, or even the website, you get to see beautiful pics and videos of all the things we’re trying to protect, but you also get alerts when you can add your name to letters, actions and petitions. Some of our best defenders have been helping us since they were in primary school and now they’re grownups. Lots of young people contributed to stopping those industrial projects and to getting the marine park up. But we still need to secure the whale refuge (which is also a dolphin, dugong, sawfish refuge).

This interview also appears at CBCA’s Reading Time

Tim Winton & Juice at Paperbark Words blog

One thought on “Tim Winton Interview about Ningaloo”